The Healthy Glamour of Everyday Life

The Hammer Museum's "Heat Waves in a Swamp: The Paintings of Charles Burchfield" is extraordinary on many levels. It's the first full-scale Burchfield retrospective ever on the West Coast. It's also one of the best shows of pre-Rauschenberg American art to play Los Angeles. It's a big painting show that contains exactly two oil paintings. That's because practically all of Burchfield's achievement in is watercolor. The show's curator is Robert Gober, the prominent contemporary sculptor. Affinities between Burchfield's and Gober's work are hard to discern, though the show had its genesis in the fact that Gober owns a Burchfield drawing. You expect artist-curated shows to be different, foregrounding the brilliance of the curating artist and slighting those unfortunate souls being curated. The most amazing thing about "Heat Waves" is that it's not a Robert Gober "installation"; it's the best and brightest Charles Burchfield show you could hope for.

The Hammer Museum's "Heat Waves in a Swamp: The Paintings of Charles Burchfield" is extraordinary on many levels. It's the first full-scale Burchfield retrospective ever on the West Coast. It's also one of the best shows of pre-Rauschenberg American art to play Los Angeles. It's a big painting show that contains exactly two oil paintings. That's because practically all of Burchfield's achievement in is watercolor. The show's curator is Robert Gober, the prominent contemporary sculptor. Affinities between Burchfield's and Gober's work are hard to discern, though the show had its genesis in the fact that Gober owns a Burchfield drawing. You expect artist-curated shows to be different, foregrounding the brilliance of the curating artist and slighting those unfortunate souls being curated. The most amazing thing about "Heat Waves" is that it's not a Robert Gober "installation"; it's the best and brightest Charles Burchfield show you could hope for.Burchfield was unacademic and uncareer-oriented, a bit of an irony given that the Hammer is affiliated with one of the foremost art academies around. He bailed out of art school after one day — yet was the first artist to get a solo show at the Museum of Modern Art — which he didn't bother to attend. Instead he sent Alfred Barr a nice handwritten note. It's on view here.

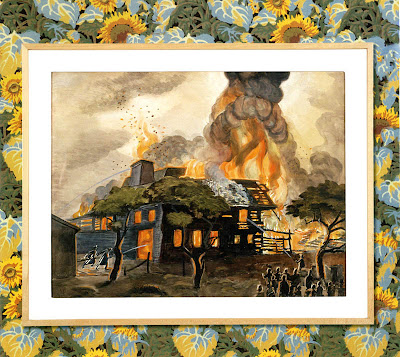

Burchfield portrayed what he called "the healthy glamour of everyday life," generally with a twist of Lemony Snicket. Above is 1929's Pyramid of Flame, celebrating the luminous effects of a local house fire. He delights in chaos, rubble, weeds, insects, frost, night, thunderheads, and the tricks humidity plays with light. Gober's installation breaks a massive chronology into thematic rooms. The first is a skeleton key to Burchfield, a set of near-abstract drawings, weirdly rhyming with those in the the Georgia O'Keeffe abstraction show currently at New York's Whitney Museum (where the Burchfield show will travel). For Burchfield, these drawings were an animator's reference studies, motifs he would recycle to achieve the anthropomorphism of his houses and landscapes.

Another room presents the "golden year" of c. 1917. Alfred Barr zeroed in on this period when he gave Burchfield his 1930 MoMA show, sensing it was more germane to modernism that the American Scene works that followed. This room is followed by a real show-stopper, a galley of 1920s works hung against a reproduction of a sunflowers wallpaper design that Burchfield created in his day job. Then there's a room of doodles, literally from a pad by the Burchfield residence's phone. You expect to breeze through this part — instead, it rivals Miro, with a bit of Scott Kim thrown in. Burchfield would write someone's name, mirror-reflect it in a vertical axis, and turn the result into a scary insect. The phone doodles alone would have made one heck of a drawing show.

The best room is the last, containing the large landscape fantasias of the postwar era, up until the artist's 1967 death. (Left, The Sphinx and the Milky Way, 1946; below, Gateway to September, 1946-56). These pieces are so incredible that it's hard not to wonder, why isn't Burchfield better known?

He was well known in mid-20th-century. Burchfield was written up in Time magazine and — like Benton and Wood — had a populist image as a small-town, family-man artist, untainted by Europe and the madder sort of modernism. Curiously, Burchfield comes off more as a Jim Thompson anti-hero in his private journals, a man of unnamed sins who is only acting the role of an average citizen. He was The Man Who Wasn't There.

As the art world dug its way out of depression, Burchfield accepted commissions from Fortune magazine (where he looks very Charles Sheeler) and even from Johnnie Walker, for an ad featuring their whiskey against a fecund Burchfield landscape.

As the art world dug its way out of depression, Burchfield accepted commissions from Fortune magazine (where he looks very Charles Sheeler) and even from Johnnie Walker, for an ad featuring their whiskey against a fecund Burchfield landscape. Burchfield's relatively low profile today must reflect his chosen medium. Watercolor fades quickly on exposure to light. For that reason his watercolors can't be shown in museums' painting galleries alongside Hopper and Gorky. Out of sight is out of mind — in art history especially. Yet Burchfield did do oils. The two examples here, both from the Whitney, are from his middle, American scene period, the least esteemed phase now. The space-strapped Whitney almost never shows them. They're well-crafted works, of a piece with his watercolors of the period and making use of the luminosity of oil. Why didn't Burchfield do more in oil, if only to put bread on the table in those desperate years?

Comments

In the fall of 1980, "Charles Burchfield: The Charles Rand Penney Collection," a touring Smithsonian show, appeared at the Bowers Museum in Santa Ana. Among scores of prints and drawings, including some of those wonderfully obsessive "doodles," only about a half-dozen mature works were included.

It is mostly to the picture plane, no modeling, but often does have a disconcerting twisted perspective, but each depth is on a seperate level, not coming forward, but all recessed. Like a set on a stage, with each item flatly painted but placed in spots for the actors to mingle through. But there are no actors, no story to the theatricality. Not Klee's poetic puppet theatres, but ones of a detached observation, of wanting to belong, but just out of reach of the world.

Interesting, but his wallpaper is probably of a higher skill and purpose level.