Tony Conrad’s “Yellow Movie”

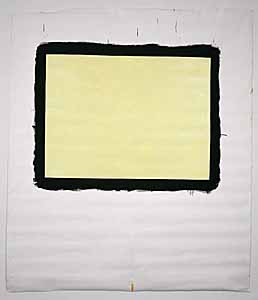

Museums take great pains to prevent light damage to works on paper. At MOCA Grand Avenue, the skylights have been darkened to permit hanging drawings and photographs next to paintings and sculpture in "Collection: MOCA's First Thirty Years." Ironically, one MOCA work may not be showing its age enough. It's Tony Conrad's Yellow Movie (pictured).

Museums take great pains to prevent light damage to works on paper. At MOCA Grand Avenue, the skylights have been darkened to permit hanging drawings and photographs next to paintings and sculpture in "Collection: MOCA's First Thirty Years." Ironically, one MOCA work may not be showing its age enough. It's Tony Conrad's Yellow Movie (pictured).Tony Conrad is roughly a John Cage of film. He came to attention with Flicker, a 1966 film consisting of black and white frames alternating. It's said to be dangerous for anyone subject to seizures. Many of Conrad's films play with duration.

Andy Warhol's Empire (1964), consisting of an eight-hour shot of the Empire State Building, provoked Conrad to imagine longer films yet. Could he somehow create a movie that would last years, or a lifetime? As Conrad told Artforum in 2007,

Andy Warhol's Empire (1964), consisting of an eight-hour shot of the Empire State Building, provoked Conrad to imagine longer films yet. Could he somehow create a movie that would last years, or a lifetime? As Conrad told Artforum in 2007,The problem was that a truly very long film won't fit on a reel. So to work at the timescale of a lifetime necessitated revisiting the whole mechanical system. Lying on my bed in my Forty-second Street loft, contemplating this problem and vacantly staring at the ceiling, I said to myself, Crap! I just painted the ceiling last year, and look at it, already yellow! At this point I realized cheap house paint had exactly the emulsion properties I was interested in: environmental responsiveness over a very, very long scale of time.

The idea was that a painting made with cheap white housepaint would yellow with age. This would constitute a changing image, call it a "movie," lasting years or decades. "I thought about furniture pulled away from the wall showing its photograph on the wall in an indistinct but precise manner," Conrad explained. "I realized that if I used cheap house paint as an emulsion, people who wanted to be in my 'Yellow Movies' could stand against them for, say, a year or two and leave their trace embedded in them in a monumental way."

Conrad made 20 Yellow Movies and showed them for a one-day "screening" in New York in 1973. Since the movies were supposed to be yellow, Conrad tinted some with yellow pigment. MOCA's movie is light citron framed in black. When the Yellow Movies were reshown in Cologne and New York in 2007, Conrad felt they looked "pretty white for movies that are supposed to turn yellow." Apparently, the yellowing of white paint is more about dirt than light. It requires smog, urban grit, and cooking fumes. Artworks are normally protected from that sort of thing.

Conrad seems more relevant than ever to an art world obsessed with finding connections between art and film. At least one good example is in MOCA's "Collection" show, Hiroshi Sugimoto's Cinerama Dome, Hollywood (1993, displayed at the Geffen). In a way, it's the conceptual opposite of the Yellow Movies. Sugimoto used long exposure to compress hours of a "moving picture" onto a still image.

Conrad seems more relevant than ever to an art world obsessed with finding connections between art and film. At least one good example is in MOCA's "Collection" show, Hiroshi Sugimoto's Cinerama Dome, Hollywood (1993, displayed at the Geffen). In a way, it's the conceptual opposite of the Yellow Movies. Sugimoto used long exposure to compress hours of a "moving picture" onto a still image.

Comments

Besides, he is cheating on his own irrelevant question by toning the paint. Wow, now thats really important stuff.LOL!

Seriously, art collegia delenda est

Save the Watts Towers, tear down the Ivories