Institute of Contemporary Art Opens

|

| Sarah Cain's Now I'm going to tell you everything in the ICA LA courtyard |

|

| View of Abigail DeVille's No Space Hidden (Shelter), in ICA LA Project Room |

|

| Main exhibition space, showing works by Martín Ramírez |

Martín Ramírez. "Martín Ramírez: His Life in Pictures, Another Interpretation" would be a coup in any season. It's a particularly apt PST LA/LA entry, as Ramírez's unusual life exemplifies the border and napantla ("in the middle of it"). Born in Tepatitlán, Jalisco, Ramírez (1895-1963) fled his family and revolutionary violence to work on U.S. railroads. The Depression threw him out of work. Estranged from his family and homeless, he was diagnosed as schizophrenic and spent the rest of his life in California mental hospitals. His art, cobbled from humble materials, has long been compared to Art Nouveau, Bridget Riley, and Henry Darger. Ramirez's hypnotic curves long preceded Riley's Op.

Like Darger Ramírez was first appreciated by the ever-perceptive Chicago Imagists. Many of the works in this exhibition are lent from the collection of Jim Nutt and Gladys Nilsson.

|

| Martín Ramírez, Horse and Rider with Frieze, collection of Jim Nutt and Gladys Nilsson |

In recent years scholars have questioned whether Ramirez was schizophrenic. At the time mental hospitals often functioned as homeless shelters. The ICA exhibition, curated by Elsa Longhauser, attempts to understand Ramírez's art through his biography and Mexican pop culture. The horse and rider was a traditional motif, and it's known that Ramírez rode horses and had a pistol in Jalisco. The trains and tunnels reflect his years working on the railroads. The "Op art" lines must be topographic maps of a kind, reflecting a memoryscape of Southwestern canyons.

|

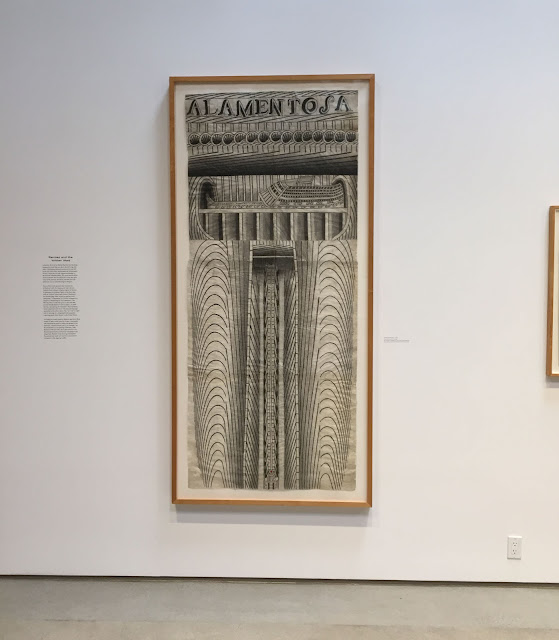

| Martín Ramírez, Vertical Tunnel with Cars and AUANA CUUA |

Freudian interpretations of Ramírez's tunnels and trains are obvious enough. One example is inscribed by the artist "AUANA CUUA." Apparently nonsense, it may be a phonetic spelling of "Havana, Cuba," referring to news reportage of the Cuban missile crisis. That would make it one of the artist's last works. The spiky structures at upper center are similar to those identified in other drawings as galleons. That might link Spanish galleons to the U.S. naval blocade of Cuba.

The ICA LA show debuts a newly conserved scroll drawing-painting-collage. It's not the most satisfying work here, but it's interesting for its ambition and apparent biographic theme. Reading from left to right, it moves from idyllic animals in a Mexican Eden to a canyon railroad that ultimately disappears, like a Chuck Jones Roadrunner cartoon, into a tunnel that is only painted and which may portend catastrophe.

The benches. Clever gallery seating is becoming a thing. ICA LA's benches plays off Donald Judd's furniture for Marfa, with a nod to De Stijl and Sherrie Levine (the white plywood knots).

The parking. At 1717 Seventh St., ICA LA is towards the southern end of the Arts District. The nearest Metro station (Little Tokyo/Arts District, Gold line) is a 1.2 mile hike. ICA LA exists in a desert of parking lots, but most are private, and ICA does not have any parking of its own. The closest public parking lot is a 7 minute walk away, at 660 Mateo Street. It's reasonably priced ($5). There is some street parking within a few blocks.

The artists' museum. The roster of artist-patrons exceeds that of MOCA or any other L.A. museum I know of. "Artists for an ICA LA" includes all the "MOCA Four" board members who quit in protest over Jeffrey Deitch's disco show, or something like that, in 2013.

Comments