|

| Guan Rong, Oswaldo Gonzalez, Erik Newman, and Sara Velas, The Grand Moving Mirror of California, 2010. Collection of the Velaslavasay Panorama, Los Angeles |

Today's immersive pop-up attractions have their roots in panoramas. As patented by Irish artist-inventor Robert Barker in 1787, a panorama is an immense circular painting, with the viewers in the middle. Spanning the entire field of vision, the painted surface simulates the experience of being somewhere else in space and time. Like "Immersive van Gogh," panoramas were hugely popular while having a problematic relationship to so-called real art. These paradoxes are productively revisited in a new exhibition at the at the Forest Lawn Museum, Glendale, "Grand Views: The Immersive World of Panoramas." It's a collaboration of two of L.A.'s quirkier alternative spaces, the hipster Velaslavasay Panorama and the kitsch-positive Forest Lawn Museum.

Both institutions have unique connections to the subject matter. Forest Lawn founder Hubert Eaton had an abiding belief in the power of art to draw pre-need customers. He bought a mothballed panorama, Jan Styka's The Crucifixion, and installed it as a light-and-narration tourist attraction in his Glendale cemetery. Sara Velas, founder of the Velaslavasay Panorama in West Adams, is one of the few contemporary artists to create panoramas and present them in a vaguely 19th-century mode. Not unlike the Museum of Jurassic Technology, the Velaslavasay Panorama is a contemporary institution that feigns a steampunk history.

The exhibition is divided into three parts: the history of panoramas as a global phenomenon; panoramas of the crucifixion; panoramas in Los Angeles and their contemporary legacy.

|

| Unknown artist, Section of the Rotunda, Leicester Square, in which is exhibited the Panorama, 1801 |

Robert Barker struck it rich by charging Londoners 3 shillings to view his 360-degree view of Edinburgh. It was followed by a half-circle view of London itself. Architect Robert Mitchell's Leicester Square building, opened in 1793, allowed two panoramas to be shown at once.

|

| Unknown artist, Poster for Charles Castellani's "Le Tout Paris" Panorama, 1889 |

Static views of distant lands were ultimately eclipsed by battle scenes and celebrity culture. "Le Tout Paris" included recognizable celebrities of the time. Other panoramas incorporated lighting effects, motion, and 3D elements (

faux terrain).

|

| Unknown artist, Key to Nomura Yoshimitsu's Panorama of "Aidsu-Great-Battle", 1900 |

Panoramas were particularly popular in Meiji Japan. This print is a circular key, allowing the visitor to identify places and events in a depicted battle crucial to the "Civil War of Japan."

|

| Martin Behrman, Battle of Paris Panorama Building, 1888. Los Angeles Public Library |

Los Angeles had panoramas before it had movies. A view of the Siege of Paris, painted by Henri Felix Emmanuel Philippoteaux, was installed in a circular building on Main Street in 1887.

|

| Sigmund Strobel Kiffaludy, Jan Styka. Forest Lawn, Glendale |

Jan Styka (1858-1925) was Poland's great panorama artist. His panoramic oeuvre was small (occupational hazard), consisting of just four very big paintings. Forest Lawn founder Eaton learned of the hard-luck story of one,

Golgotha (later,

The Crucifixion). It was a half-circle painting, 195 ft long by 45 ft high, that was acclaimed a masterpiece when shown in Warsaw in 1887. It then began a world tour that halted at the St. Louis world fair of 1904. There had been a confusion about dimensions, and the fair did not have a space large enough to show Styka's painting. Worse, the organizers failed to pay the customs tax, so the panorama was seized by tax authorities. Styka had to return home without it. He never saw it again.

|

| Pope Leo XIII blessed the palette Styka used to paint The Crucifixion |

|

| Unknown photographer, Hall of Crucifixion Billboard, 1951. Forest Lawn Museum |

In the decades that followed, modernism and the movies made panoramas all but obsolete. Eaton located Styka's painting, wrapped around a telephone in the basement of the Chicago Civic Opera Company. He bought it for a pittance and had it restored by Styka's son. Put on display at Forest Lawn, it was billed as America's largest religious painting. (

A panorama of the Battle of Gettysburg is larger, at 377 ft. long by 42 ft. high. Richard Neutra designed a modernist cylinder to house it, but the National Park Service demolished it in 2013.)

No sooner had Eaton secured his big picture than he was planning a sequel. A crucifixion is a downer, at odds with Forest Lawn's sanitized spin on death (satirized in Evelyn Waugh's The Loved One). Eaton held a competition for designs for a similarly large painting of the Resurrection, to be shown alternately in the same building.

|

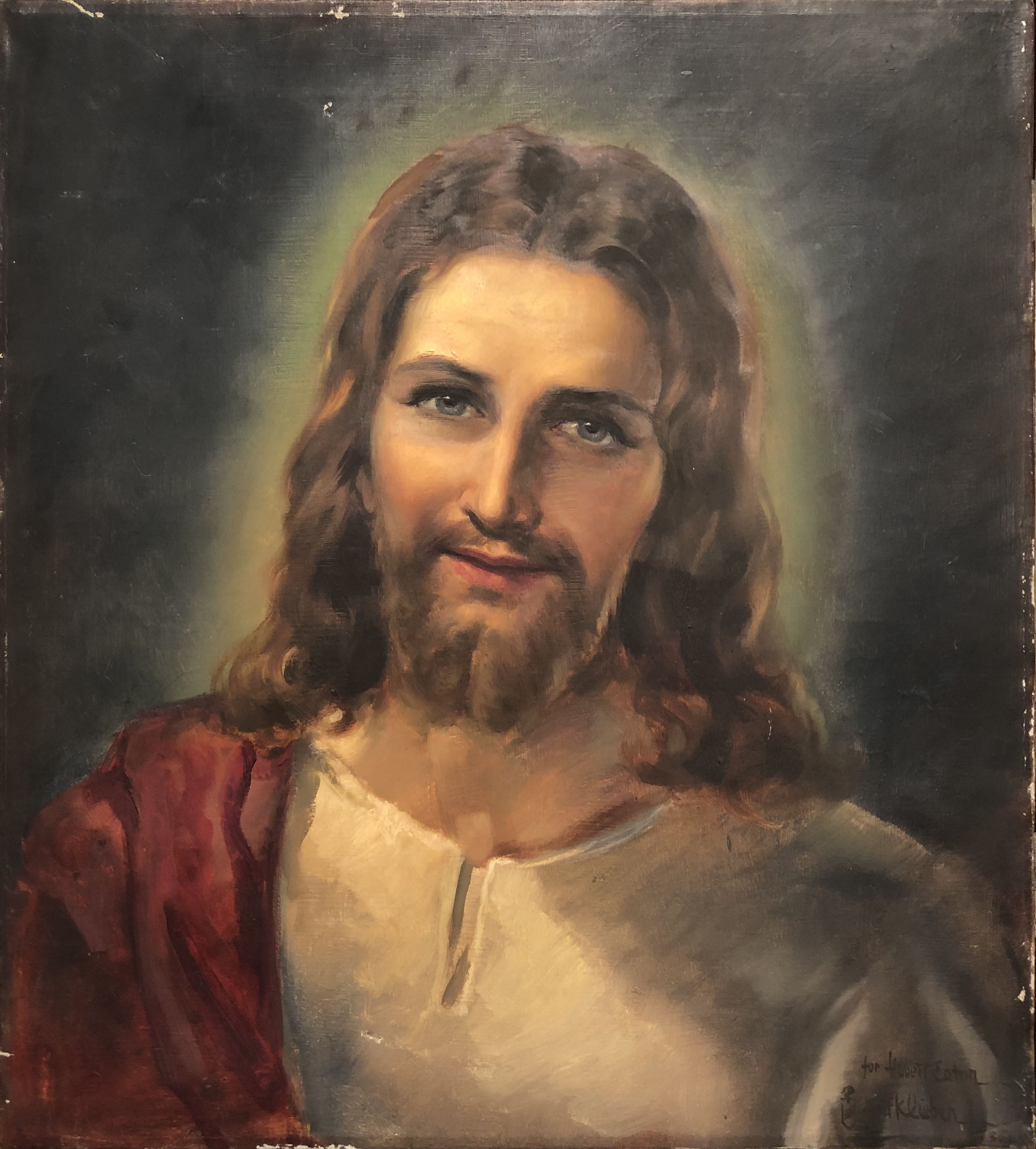

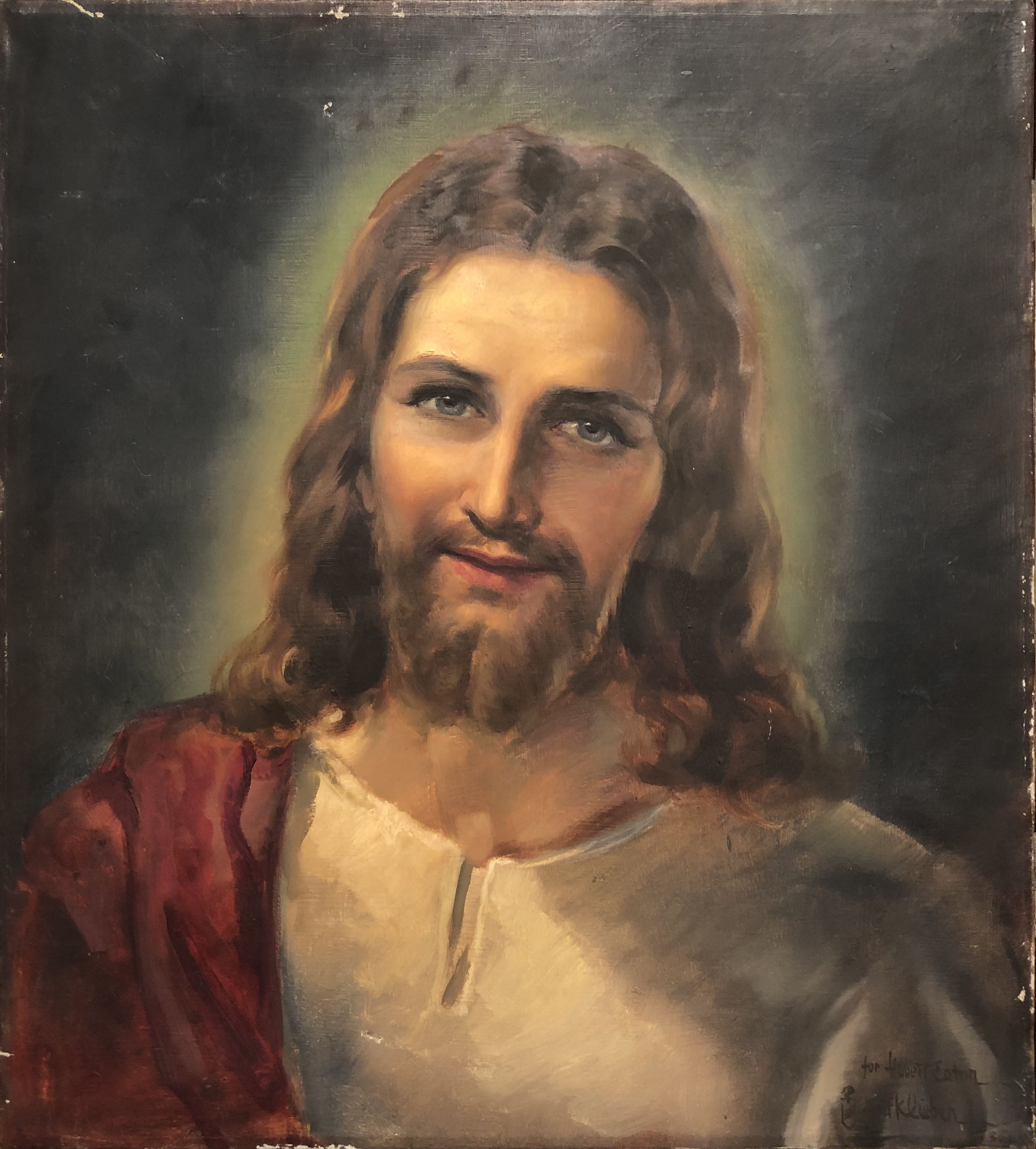

| Unknown photographer, Dr. Hubert Eaton searching for Smiling Christ, about 1952. Forest Lawn Museum |

One of Eaton's requirements was a "Smiling Christ." He felt that too many pictures made Jesus look like a Gloomy Gus. There's a truly weird publicity photo of Eaton "searching for Smiling Christ." To the right is a colossal, very white Jesus with Margaret Keane eyes.

That photo includes this study by German artist Paul Von Klieben. He was Art Director for Knott's Berry Farm (there's something to put on your resume).

|

| Paul Von Klieben, Preliminary Study for Smiling Christ, about 1952. Forest Lawn Museum |

Eaton was a difficult taskmaster. The exhibition includes a photograph of an early Resurrection sketch bristling with handwritten notes. Part of the story goes untold here. After all the nitpicking, the final Resurrection painting (by Robert Clark) shows Jesus in profile. Did someone pull Eaton aside and tell him that Smiling Jesus wasn't going to work?

|

| Installation view with matte painting of Washington, DC, 1955. Collection of Bryan Jackson |

Panoramas had a lingering influence on the movie business. Matte backdrop paintings were hand-crafted landscapes in the service of a seamless illusion. The Cinerama process blended

cinema and

panorama. It required a curved screen, such as Hollywood's Cinerama Dome, limiting the number of adopters.

|

| Stanley Warner Cinerama Corporation, This is Cinerama Re-release Poster, 1973 |

|

| Sara Velas, Panorama of the Valley of the Smokes (small detail), 2001. The Velaslavasay Panorama |

Sara Velas revived proper panoramas in 2001 with her

Valley of the Smokes. It's a history painting with almost no history, representing a quieter, more natural Los Angeles basin of about 1800. Measuring 60 feet wide, it was nonetheless shown in the round, the first such panorama on view in Los Angeles for a century. The current exhibition displays the full painting, flattened to one wall.

|

| Sara Velas, Valley of the Smokes |

|

| Sara Velas, portions of Effulgence of the North with faux terrain, 2005-2007. The Velaslavasay Panorama |

Effulgence of the North is a fantasy based on texts and photographs of polar voyages. As originally presented, it incorporated fake icebergs (

faux terrain) sculpted by Asami Morita and an ambient soundscape by Moritz Fehr. The ever-cycling lighting, by Velas and Paula Peng, used phosphorescent paint to simulate the aurora borealis.

|

| Jan Styka, The Crucifixion, 1897. Forest Lawn, Glendale |

"Grand Views" runs through Sep. 10, 2023. Don't leave without checking out Styka's

The Crucifixion next door.

Yes, it a big, conservative religious painting, unfashionable and irrelevant. It's also a found installation, as much Eaton's as Styka's. Eaton elected to flatten the painting's half-circle into a super-sized movie screen. This allowed a full half circle of seating. Eaton must have expected mobs, and as the exhibition demonstrates, tickets and assigned seats were required in the 1950s. The velvet seats are still meticulously lettered and numbered, like it's the Hollywood Bowl.

The structure is one of the most amazing spaces in greater Los Angeles—and it's almost always empty. It can be read as unintended commentary on a changing creative landscape. The pictures are still big—it's the audiences that have gotten small.

Comments

See in the NGA/DC collection Sugimoto's Tri City Drive-In, San Bernardino, 1993.

NGA describes the picture thus [link at bottom]:

A movie screen is bright white against a dark gray sky, trees, and a playground in this horizontal, black and white photograph. The screen takes up about a quarter of the overall composition, just above the center of the picture. It is raised off the ground, perhaps on a wall or stage that we cannot see. Light from the screen brushes the tops of trees or shrubs growing near the bottom edge. Three sliding boards, several swing sets, and a merry-go-round fade in and out of shadow around the screen’s glow. Power lines crisscross the dark, clear sky behind the screen.

https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.161911.html

"[Sara] Velas cites two main artistic inspirations: the 19th-century German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich and flamboyant circus showman P. T. Barnum."

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/panorama-mama-100500651/

See "View from the artist's studio in Dresden on the Elbe", C.D. Friedrich

--- J. Garcin

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/13052