|

| François Willème, The Sculptor's Brother, mechanically produced relief portrait, about 1859-1861. George Eastman House, Rochester. The relief is made from about 150 brass sheets secured with bolts |

LACMA's "City of Cinema: Paris 1850-1907," co-organized with the Musée d'Orsay, explores the origin story of motion pictures, a tale intertwined with the histories of painting, photography, and popular culture. It is no surprise the early French film shared the urbanity of Impressionist painting; nor that photography supplied the foundations of cinematography and special effects. More unexpected is the dialog between sculpture, photography, and the movies. At the nexus of these media was Auguste François Willème (1830-1905).

About 1860 Willème devised photosculpture, an attempt to bring the unmediated naturalism of a photograph to sculpture. His patented technique combined photography with the pointing machine, used by sculptors to reproduce 3D art. You could say that photosculpture was a steampunk attempt at 3D printing, using the available technology of the Second Empire.

Willème's sitters posed in the middle of a glass-enclosed rotunda-studio-panopticon. Twenty-four cameras simultaneously captured images of the sitter from every angle. The resulting photos were converted to lantern slides, projected on a screen, and traced by an artist whose hand motions were transmitted by a pantograph to a sheet of wood or a cylinder of clay. Another artist then trimmed the wood or clay to conform to the pantograph's silhouette. This process was repeated 24 times, to incorporate all the image data. The resulting, quasi-cubist portrait was then refined by hand into a natural likeness and reproduced yet again in a more durable medium.

|

| Auguste François Willème, Portrait of Celeste-Rose Beauregard, 1865. LACMA |

Did it work? You can judge for yourself, as the LACMA show includes an earthenware Willème photosculpture of Celeste-Rose Beauregard, a popular comic actor known as Rose Deschamps. It is not a great sculpture, yet the drapery has a freeze-frame realism that sets it apart. It transmits something of the disruptive quality of photography into the universe of sculpture.

LACMA bought this statuette in 2020 with funds from the European Painting Deaccession Fund and the Ralph M. Parsons Fund (for photography). A hand-painted version of Beauregard exists, but this better demonstrates Willème's achievement.

During photosculpture's brief vogue, studios were set up in London and New York as well as Paris. Yet photosculpture failed as a business plan. The point was to save on skilled labor, and it didn't do that. Willème's studio went bust in 1868.

Willème nevertheless influenced artists now much better known. The photosculptures invite comparison to the serial photography of Etienne Jules Marey and Edward Muybridge, which also used ensembles of cameras dispersed in space. Photosculpture predated Muybridge's serial studies of Leland Standford's racehorse (1878) by 18 years.

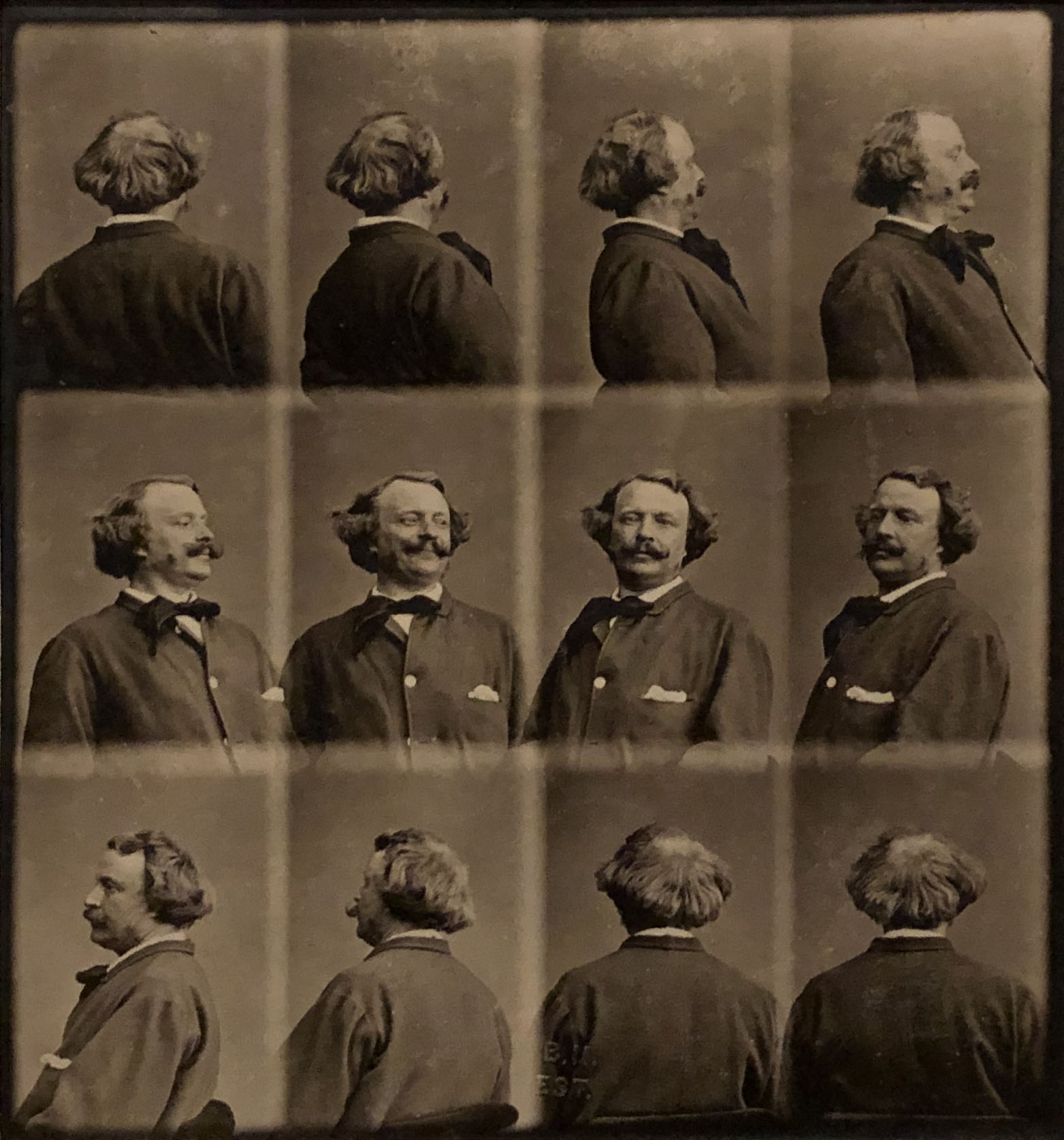

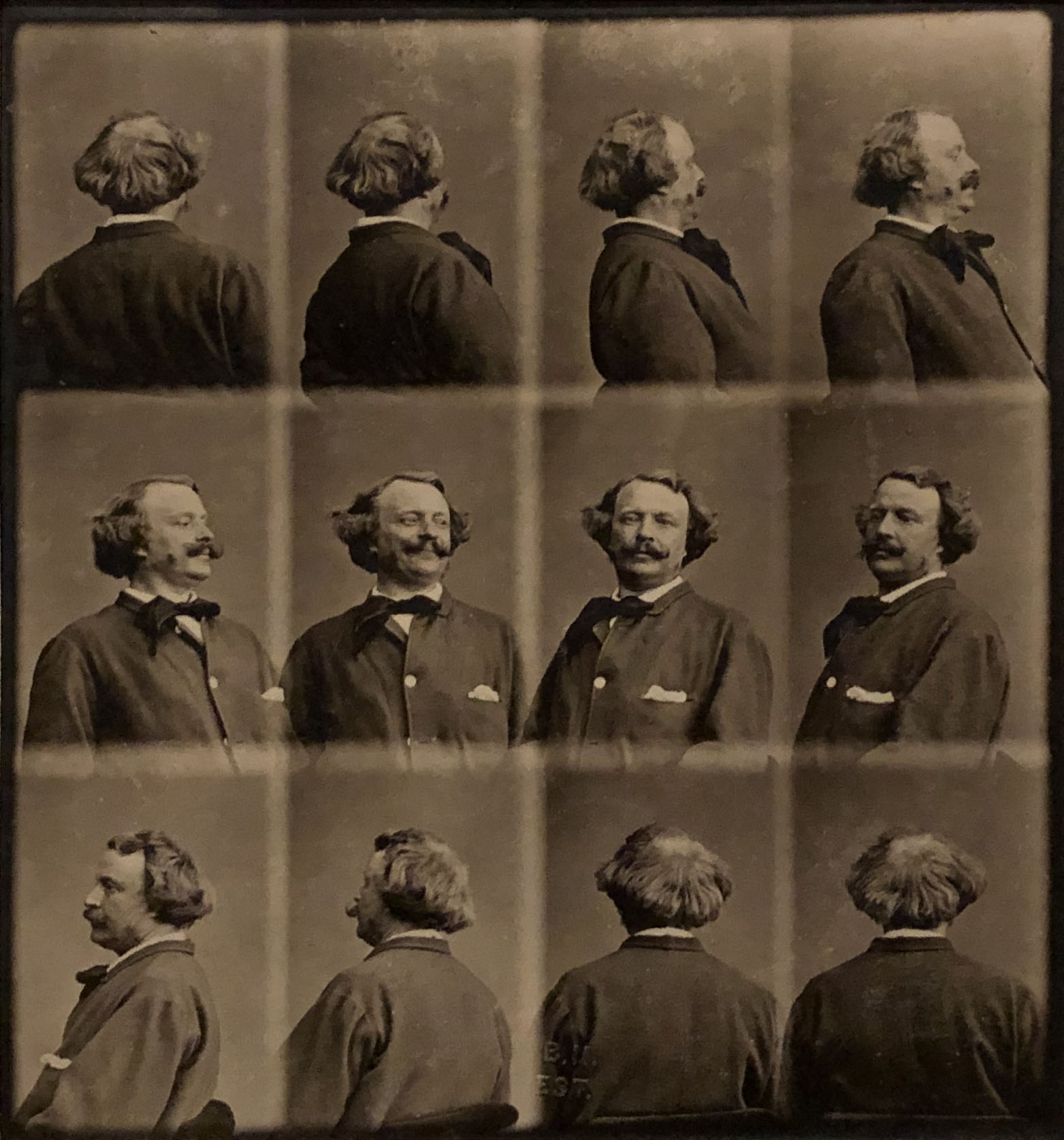

"City of Cinema" has a Study for a Photosculpture by Nadar. The title is perhaps facetious, for the 12 portraits are less than the 24 Willème required.

|

| Nadar, Self-Portraits in Twelve Poses: Study for a Photosculpture, 1861-1867. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris |

|

| Auguste Rodin, Pygmalion and Galatea, 1889. Musée Rodin, Paris |

Today camera arrays are used in the "bullet time" film effect. As the portrait of Beauregard demonstrates, photosculpture was the conceptual forerunner of today's 3D scanning of celebrities. Scan Brando or Tupac, and the intellectual property is forever.

|

| Renato Bertelli, Continuous Profile (Head of Mussolini), 1933 |

Comments

I wonder how truly reflective of the subject it really was.

Sure beats those tired black cut-out silhouettes from earlier days.

Willème was so clever. I'm reminded of avant-garde photographer Alphonse Bertillon, who pioneered the mugshot. His mugshot of his son, François Bertillon, at 23 months, taken in 1893, is seared in my memory. The kid looks guilty as sin.

See the work on-line:

https://www.moma.org/collection/works/127194?artist_id=36924&page=1&sov_referrer=artist

I feel just the opposite way. Not that the work is necessarily great, but it also doesn't seem deserving of a qualification of its quality.

In turn, some of the folds or crinkles of the figure's dress seem more tentative than ideal.