A Ventriloquism Show Rambles On… and Sings

|

| Vernacular photographs of ventriloquism in "Not I: Throwing Voices (1500 BCE-2020 CE)" |

The sleeper exhibition at the reopened LACMA is "Not I: Throwing Voices (1500 BCE-2020 CE)." It's a show about ventriloquism, more or less, and drawn primarily from the permanent collection.

I assumed that "Not I" would be small. Nope. It's insanely big, over 200 works, filling much of the Resnick Pavilion and spanning 3.5 millennia and a gulf in taste that runs from Goya to Mattel to Samuel Beckett (the title is from Beckett's "Not I," represented in a performance video.)

LACMA's "Not I" has one dummy (Frank Marshall's Elmer Sneezewood, a loan from the Autry), a few treatises on the variety act, and some campy publicity shots of mid-century vents in action. Otherwise "Not I" is a succession of puzzles. What do these objects have to do with ventriloquism or each other? Elmer Sneezewood shares a display case with No Name (1968), Nancy Grossman's leather-bound meditation on gender and power.

Another case pairs Isamu Noguchi's Radio Nurse, a classic of modern industrial design (1937), with Hendrick de Keyser the Elder's bronze Crying Child from about 1615. Both are familiar from the permanent collection galleries, back when LACMA had such things. The Crying Child evokes noise through the mute language of cast bronze. The Radio Nurse offers a technocratic solution masquerading as a modern sculpture. Crying Child is the eternal id; Radio Nurse prefigures the opt-out Orwellianism of the Internet of Things.

|

| Marcel Duchamp's With Hidden Noise (left foreground, 1916/1964), with Richmond Barthé's Inner Music (1956), and Mayan Tripod Vessel with Supernatural Palace Scene and Cacao Tree, 750-850 CE |

|

| John Baldessari, Beethoven's Trumpet (With Ear) Opus #131, 2007 |

Part of "Not I" works that way: crazy juxtapositions of works relating to voice, noise, music, or silence, of diverse media, cultures, and epochs. Another phase of the exhibition veers off onto tangents. Extended digressions include pipes, ducks, and rabbits. Huh?

|

| Ryūryūkyo Shinsai, Woman Making Rabbit Shadow for Small Boy, 1807 |

As far as I can tell, the rabbit arc launches from a woodblock print by Ryūryūkyo Shinsai, Woman Making Rabbit Shadow for Small Boy. Hand shadows are like a ventriloquist's dummy. This leads to a free association of auspicious Asian rabbits, an Ed Ruscha print of a shadowy hare, and Nayland Blake's Bottom Bunny.

|

| Ed Ruscha, Rabbit, 1986 |

|

| Nayland Blake, Bottom Bunny |

Then there's the duck subplot…

|

| Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations, 1953. Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA |

A volume of Wittgenstein is open to a discussion of the duck-rabbit illusion. This leads to a survey of ducks (which are sometimes decoys and like ventriloquist's dummies?) One of the more notable ducks is an early Kienholz assemblage that LACMA has owned since 1999. I don't remember it ever having been on view.

|

| Ed Kienholz, The U.S. Duck, or Home from the Summit, 1960 |

As Hollywood might say, "Not I" is from the twisted mind of José Luis Blondet, LACMA's curator of special initiatives. It's an organizer-driven show in which the artworks are mute props for a curatorial performance. The show has a quirky publication but no catalog, and maybe that's OK because I'm not sure any thesis is being advanced, exactly.

I loved "Not I," but I view it with some foreboding.

Michael Govan has promised to program the Zumthor building with ever-changing thematic exhibitions of the permanent collection. Presumably "Not I" is a trial balloon, as was the less successful "To Rome and Back" (2018).

Should a permanent collection display be an encyclopedia or a thought experiment?

"Not I" is a legitimate pretext for flattening hierarchies and showing works that aren't normally on view, for reasons of conservation or scare-quote quality. It encourages visitors to look at familiar works in new ways, and it could draw new audiences. (Somebody out there must like ventriloquism.)

But there's no reason outlier shows can't coexist with displays of art organized by time, space, and culture. "Not I" is an amuse-bouche that I wouldn't want for a whole meal.

|

| Chardin's Soap Bubbles (after 1739) and Gabriel Orozco's Lost Line (1993-96). Hey you kids: Get a life! |

|

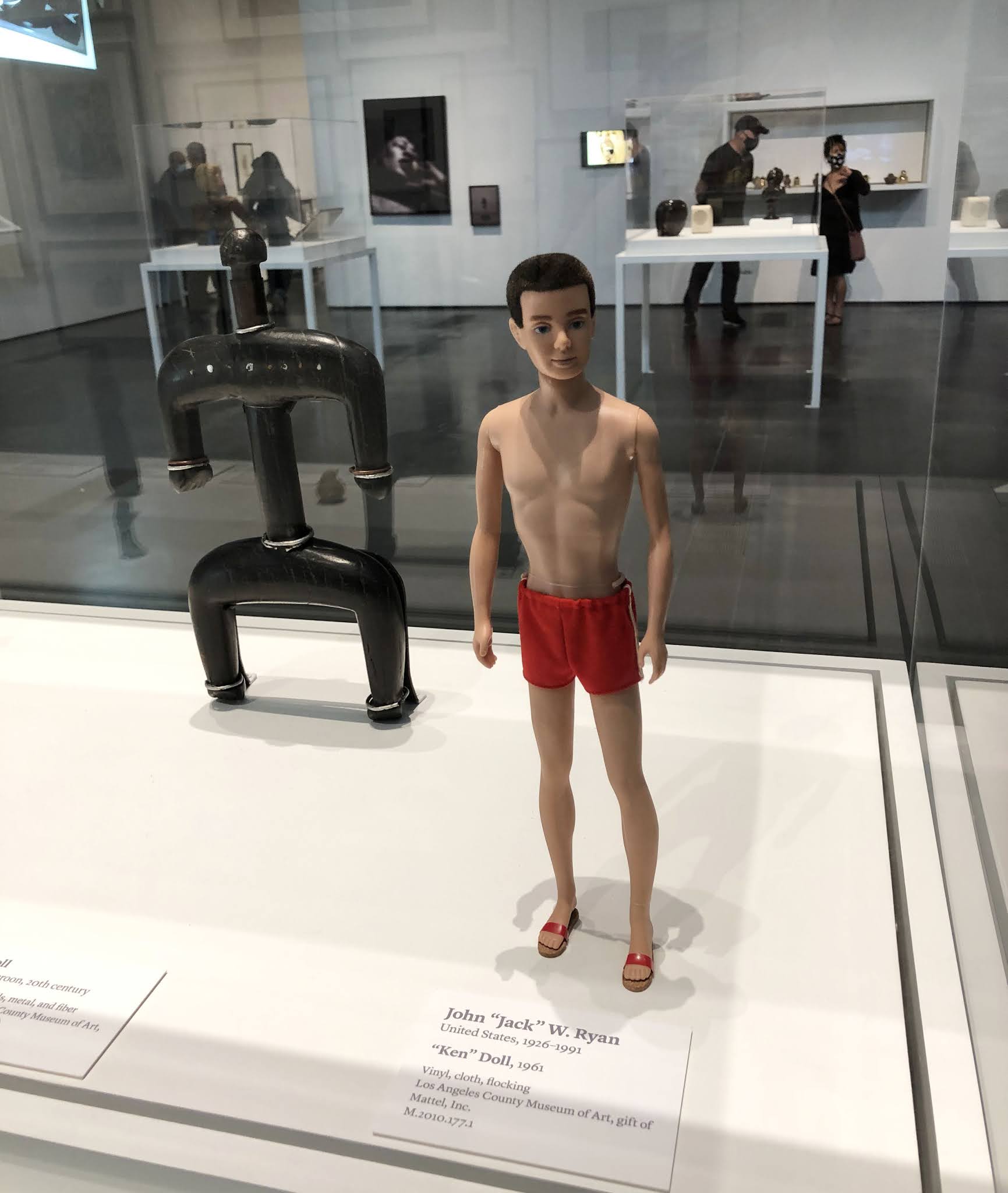

| A Namchi peoples doll, Cameroon, and a Mattel "Ken" doll, El Segundo. Both 20th century |

|

| Paul Winchell, patent for "Inverted Novelty Mask," 1961 (facsimile) |

TV ventroloquist Paul Winchell painted eyes and a nose on his chin, wore a mask in the form of a small upside-down suit, and posed for the camera upside-down. The result was "Ozwald," a freakish homunculus who spoke through Winchell's upside-down mouth. Winchell patented the idea and marketed a home version for kids. After Lee Harvey Oswald's name filled the headlines, Winchell changed the creature's name to "Mr. Goody Good."

|

| George Ohr pottery, 1890s, and Jasper Johns' Ventroloquist, 1986 (reflections of Glenn Ligon's Rückenfigur, 2009) |

|

| Adam Swisher, "Dear Person of the Future," 2008 |

Comments

I like variety and I dislike casual elitism or nonchalant snobbery. But the calculated politics roiling the world of the arts and culture in general looks like it's going to end up being the worst of both worlds. Or sort of like the Govan-Zumthor debacle and its combination of both "let them eat cake" and "we're more egalitarian than you are."

In any case, the encylopedia (as conceived by Diderot and d’Alembert) was a thought experiment, the crux of which was the index. The index unwound the alphabetical order (of the entries), opening it up to a chain of synchronic associations.

See Umberto Eco, From the Tree to the Labyrinth. As such, the “encyclopedic" museum is a misnomer. “Encyclopedic" museums are closed systems, more like a dictionary (a catalog of essences).