Rubens' Drunk Antiquity

|

| Workshop of Peter Paul Rubens (possibly Anthony van Dyck), Drunken Silenus, about 1620, National Gallery, London |

One theme Rubens copped from antiquity was Silenus, the old, sloppy-drunk follower of Bacchus. A Roman sculpture from Dresden is shown next to a Rubens drawing of it from the British Museum and a workshop painting from the National Gallery, London. At first glance the painting, Drunken Silenus, is awkward. The Santa Claus head seems askew from the bear-daddy body. On further inspection, each supporting figure is brilliantly realized. This painting is now understood to be a studio piece, but the artist may have been the young Anthony van Dyck. The grapes have been attributed to Rubens' still-life maven, Frans Snyders.

|

| Sarcophagus Panel with the Calydonian Boar Hunt, Roman, 280-90 AD, Woburn Abbey Collection, Bedfordshire, U.K.; and Peter Paul Rubens, The Calydonian Boar Hunt, 1611-12, J. Paul Getty Museum |

|

| Studio of Peter Paul Rubens, Diana and Her Nymphs on the Hunt, 1627-28. J. Paul Getty Museum |

|

| Gemma Constantiniana, Roman, 320-30 AD, Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden |

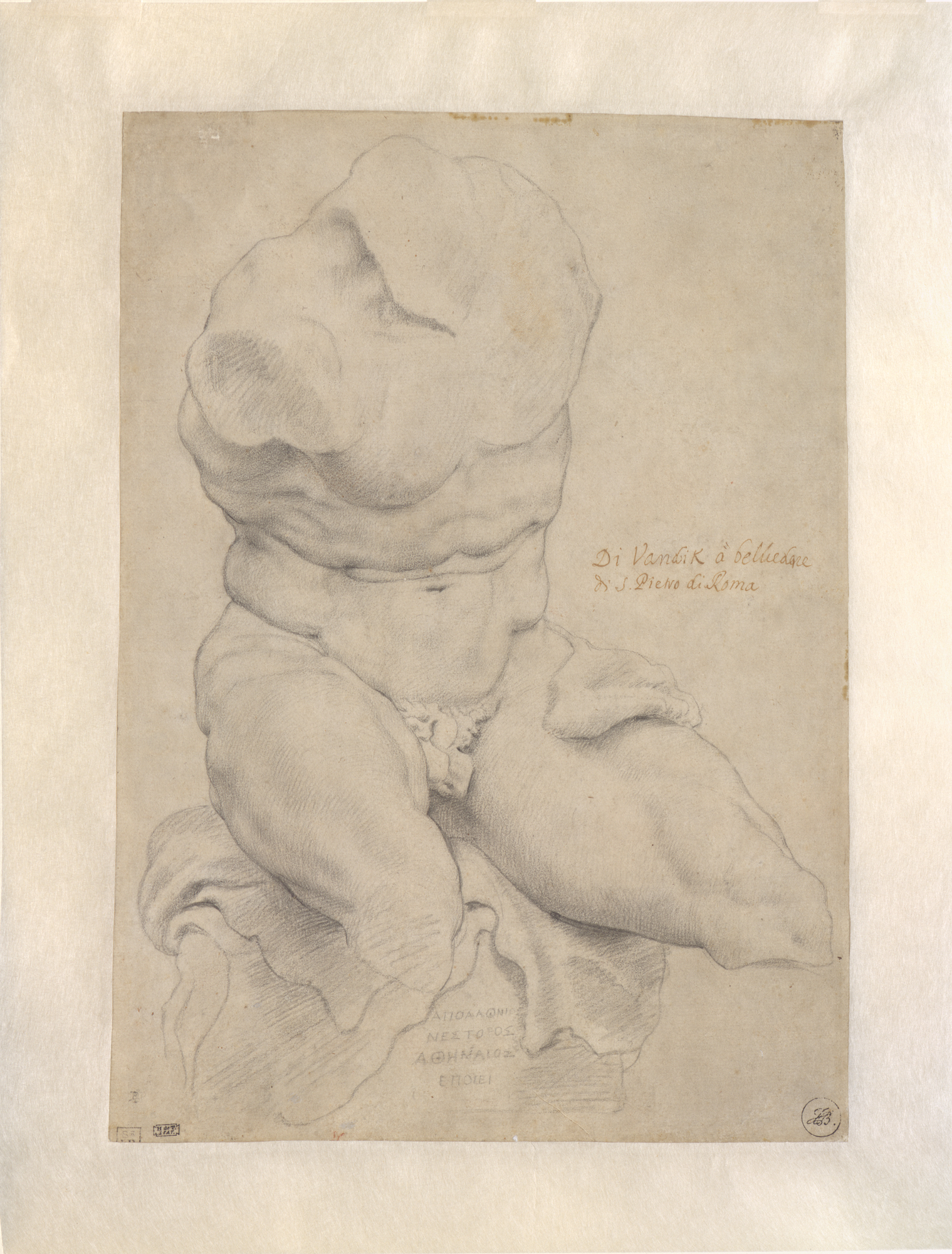

Rubens had no doubt of his ability to surpass his models. He owned a drawing from the studio of Giulio Romano and took the liberty of improving it with his own hand. He could find inspiration in the fragmentary sublime (the Belvedere Torso) and the near-ridiculous. The Gemma Constantiniana is one of the largest surviving Roman cameos, but you can probably find better craftsmanship on the Liquidation Channel. Rubens translated its visual language into one suited to the triumphal monarchs of his own day.

The show is a reminder that Rubens' art transcends that usually displayed in museums. Curators favor autograph paintings and drawings and don't quite know to what to do with collaborative ("workshop") pieces. Yet delegating execution to assistants was part of Rubens' early capitalist business plan. He spent much effort on the small and mass-produced (designing book frontispieces) and on the super-big and ephemeral (the nine double-sided, 72-ft high, painted triumphal arches for Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand—executed by others and now long gone, save in sketches and printed books).

"Rubens: Picturing Antiquity" runs through Jan. 24, 2022.

Comments

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gemma_Augustea

His polymath life has contributed prizes and gifts to the world like very few other artists.

A measure of his contributions is on display with his catalogue raisonne, known as the Corpus Rubenianum. The Corpus is a product that is more than 50 years in the making, and is hardly complete.

Brepols, the publisher of the Corpus, puts the work in apt context:

"The Corpus Rubenianum holds a unique place within Art History as one of the most ambitious projects ever undertaken. Both its massive scale and sheer duration fully parallel the complexity of the oeuvre of Peter Paul Rubens. In every brushstroke he ever painted, the grand baroque master blended art with literature, art theory with theology, mythology with history. Studying Rubens in this collaborative effort is much like studying the very foundations of European civilization, for the oeuvre of Rubens is a true treasure trove of the principal elements of our culture. Rubens's compositions are the most fascinating combinations of ideas ranging from kabbalah to Greco-Roman mythology, from optics to image-theology, from linguistics to archeology, or from politics to ethics (not to mention esthetics)."

The Corpus is planned with nearly 30 parts, each part comprising up to three volumes.

So far the following volumes have been published [as of 2018], authored by many of the preeminent Rubens scholars in the world:

I John Rupert Martin, The Ceiling Paintings for the Jesuit Church in Antwerp, 1968;

II Nora De Poorter, The Eucharist Series, 2 vols. 1978;

III R.-A. d’Hulst & M. Vandenven, The Old Testament, 1989;

V (1). Hans Devisscher & Hans Vlieghe, The Life of Christ Before the Passion: the Youth of Christ, 2014 (2 vols.);

VI J. Richard Judson, The Passion of Christ, 2000;

VII David Freedberg, The Life of Christ After the Passion, 1984;

VIII Hans Vlieghe, Saints, 2 vols. 1972–1973;

IX Svetlana Alpers, The Decoration of the Torre de la Parada, 1971;

X Egbert Haverkamp-Begemann, The Achilles Series, 1975;

XIII Elizabeth McGrath, Arnout Balis, Subjects from History, 2 vols, 1997;

XIII (Part 3). Koenraad Brosens, Subjects from History. The Constantine Series, 2011;

XV Gregory Martin, The Ceiling Decoration of the Banqueting Hall, 2 vols. 2005;

XVI John Rupert Martin, The Decorations for the Pompa Introitus Ferdinandi, 1972;

XVIII (1). Wolfgang Adler, Landscapes, 1982;

XVIII (2). Arnout Balis, Landscapes and Hunting Scenes, 1986;

XIX (1). Frances Huemer, Portraits Painted in Foreign Countries, 1977;

XIX (2). Hans Vlieghe, Portraits of Identified Sitters Painted in Antwerp, 1987;

XXI J. Richard Judson & C. Van de Velde, Book Illustrations and Title Pages, 2 vols, 1977;

XXII (1). Herbert W. Rott, Architecture and Architectural Sculpture. Palazzi di Genova, 2 vols., 2002;

XXIII Marjon Van der Meulen, Copies After the Antique, 3 vols. 1994;

XXIV Kristin Lohse Belkin, The Costume Book, 1978;

XXVI (1). Kristin Lohse Belkin, Copies and Adaptations from Renaissance and Later Artists. German and Netherlandish Artists, 2 vols., 2009;

XXVI (2.1). Jeremy Wood, Copies and Adaptations from Renaissance and Later Artists. Italian Masters

I. Raphael and his School, 2 vols. 2010;

XXVI (2.2). Jeremy Wood, Copies and Adaptations from Renaissance and Later Artists. Italian Masters

II. Titian and North Italian Art, 2 vols. 2010;

XXVI (2.3). Jeremy Wood, Copies and Adaptations from Renaissance and Later Artists. Italian Masters

III. Artists working in Central Italy and France, 2 vols, 2011;

XI (1). E. McGrath, G. Martin, F. Healy, B. Schepers, C. Van de Velde, K. de Clippel, Mythological Subjects; Achilles to the Graces, 2 vols. 2016

*****

***

The following volumes still need to be published, with authors not yet assigned (as of 2018):

IV The Holy Trinity, Life of the Virgin, Madonnas, Holy Family;

V (2). The Life of Christ Before the Passion: the Ministry of Christ;

XI (2). Mythological Subjects H–O;

XI (3). Mythological Subjects O–Z;

XII Allegories and Subjects from Literature;

XIII (2). Subjects from History. The Decius Mus Series;

XIV (1). The Medici Series;

XIV (2). The Henry IV Series;

XVII Genre Scenes;

XIX (3). Portraits of Unidentified Sitters;

XIX (4). Portraits after Existing Prototypes;

XX (1). Anatomical Studies;

XX (2). Study Heads;

XXII (2). Architecture and Architectural Sculpture. The Rubens House;

XXII (3). Architecture and Architectural Sculpture. The Jesuit Church;

XXII (4). Architecture and Architectural Sculpture. Architectural Sculpture;

XXII (5). Architecture and Architectural Sculpture. Sculpture and Designs for Decorative Art;

XXV The Theoretical Notebook;

XXVII (1). Works in Collaboration: Brueghel;

XXVII (2). Works in Collaboration: Other Masters;

XXVIII Drawings Not Related to the Above Subjects;

XXIX Addenda.

Really?

One would NOT know that from how he has been largely ignored by some studies of "the very foundations of European civilization."

For example, in Foucault's The Order of Things (a history of the "foundations" of European knowledge), it's Manet who gets the star treatment.

Ruben's work is not even mentioned in Deleuze's book on Baroque thought and culture, The Fold. And, it's not like Deleuze did not draw examples of the "fold" from art history.

Joseph Garcin

It's Velazquez who gets the star treatment in The Order of Things, specifically his painting Las Meninas.

Apt, again.

His portrait of Innocent X at the Doria Pamphilj Gallery in Rome, to my mind, is the world's most beautiful painting.

A salient excerpt treats Rubens's uneven reception among America's robber barons in the late 19th-early 20th century:

"[]Rubens’s oeuvre [] was less popular with wealthy American collectors at the turn of the [20th] century. The German art historian Wilhelm Valentiner, in his book "Rubens paintings in America" (1946) gave us an overview of the American market for the artist at that time. According to him, Rubens was the last of the great Dutch and Flemish masters to be appreciated by the American private collectors and museums. Rembrandt and Hals were the heroes of the first generation. Rubens was less sought after because of the puritanical prejudice against the sensuous nature of his art. Many American millionaires such as Frick, Altman, Mellon or Widener did not like Rubens’s style and did not buy his paintings. Only Morgan acquired half a dozen works which were, in Valentiner’s own words, ‘not of equal quality’. The 1920’s and 1930’s saw a new vogue for Rubens in Europe, which resulted in the American market showing more interest for the artist towards the middle of the 1930’s.