Two Questions About Reynolds' "Portrait of Mai"

|

| Joshua Reynolds, Portrait of Mai (Omai), about 1776. National Portrait Gallery, London, and Getty Museum |

(1) Is $62 million way too much to pay for a Joshua Reynolds painting? (2) Is it insane to ship a painting between London and Los Angeles in perpetuity?

Britain's National Portrait Gallery and the Getty will be sharing ownership of Reynolds' Portrait of Mai, depicting one of the first Pacific Islanders to visit England. Mai ("Omai," or most properly Ma'i) was born on Raiatea, an island near Tahiti. He escaped slavery after Chief Puni of Bora Bora conquered Raiatea in 1763. Mai encountered Captain Cook's expedition in Tahiti and talked himself into a post as a seaman for the return voyage. He presented himself as expert navigator.

Mai's people skills were better than his navigation skills. He charmed the crew and, after landing in 1774, London society. Some mistook him for island aristocracy. "There was nothing regal or patrician about Mai," wrote historian Hampton Sides. "He was a nobody who happened to hitch an epic ride to England, a regular guy who went on a most excellent adventure."

Mai's aim was to secure Western military aid to repel the Bora Borans. He found however that the British insisted on viewing him as a specimen of Rousseau's "noble savage." They did not want to hear that Tahiti was a rat race.

|

| Joshua Reynolds, Omai of the Friendly Isles, about 1774. National Library of Australia |

|

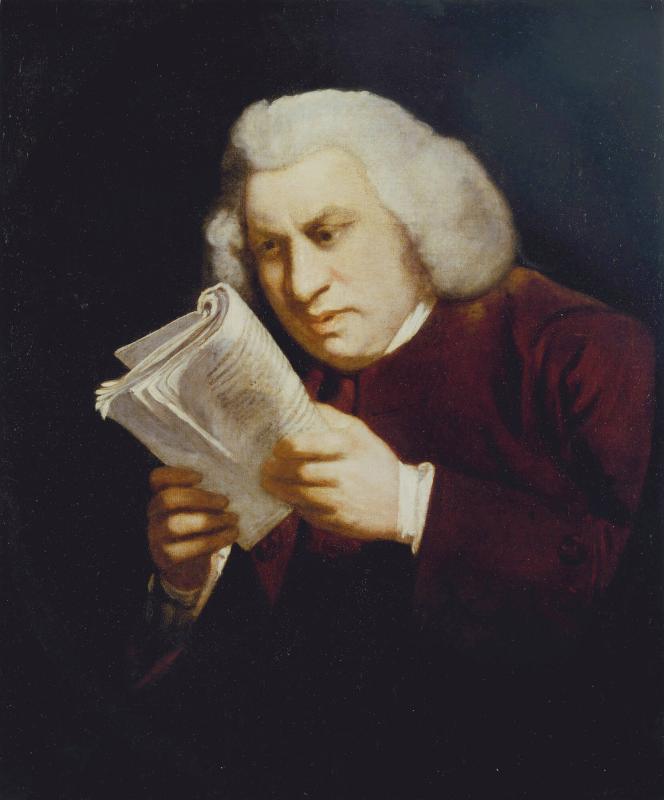

| Joshua Reynolds, Portrait of Samuel Johnson, 1775. Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens |

Rousseau held that people are naturally good and that it is civilization that corrupts. Mai's amiability, intelligence (he beat Europeans at chess), and good looks were taken as proof. One skeptic was dictionary maven Samuel Johnson, a friend of Reynolds. Johnson countered that people are determined by their environment. Mai moved in London's best circles, so he acted as a perfect British gentleman. Mai seemed to offer the British multivalent proof of all their social theories.

When presented to King George III, Mai announced, "Sir, you are king of England, king of Tahiti. I am your subject, come here for gunpowder to destroy the people of Bora Bora, our enemy."

It was a bad time to ask for regime change. George had rebellious American subjects to worry about. Ultimately George's Britain granted Mai a golden parachute. The islander was returned to the neutral island of Huahine on Captain Cook's third expedition to Polynesia. Cook set Mai up in British style, in a McManor House with Maori servants.

The West next heard of Mai from the notorious Captain Bligh. When The Bounty docked in Tahiti, in 1789, Bligh learned that Mai had died two and a half years after his return to Polynesia—maybe three years after Reynold completed his portrait. Mai would have been about 28 years old. (Compare Thomas Lawrence's Pinkie, dead practically before her portrait's paint was dry, at age 12.)

Portrait of Mai becomes the Getty's only work by Joshua Reynolds. J. Paul Getty lived in England and bought British artists from Hogarth to Walter Sickert. But his museum has shied away from building this part of the painting collection in deference to the Huntington's unmatchable holdings. The main exceptions were two Turner landscapes acquired from British collections (each occasioning UK demands to "save" the Turners for the nation).

|

| Joshua Reynolds, Sarah Siddons as the Tragic Muse, 1783-1784. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens |

British media have described Portrait of Mai as Reynolds' greatest painting. That of course is a matter of taste. A century ago, when Henry Huntington bought Reynolds' Sarah Siddons as the Tragic Muse, it too was the stuff of superlatives. Thomas Lawrence had rated Sarah Siddons as "indisputably the finest female portrait in the world"—better, in other words, than the Mona Lisa.

|

| Joshua Reynolds, Portrait of Frederick, 5th Earl of Carlisle, 1769. Tate Gallery |

That leads us to (1), the price of £50 million/$62 million. There aren't any direct comparatives. The second highest amount ever paid for a Reynolds painting is $14.6 million… for this same painting. The current seller, Irish billionaire John Magnier, paid that when he bought it in 2001.

(Let no one take that as proof that art is a great investment. Magnier's profit amounts to a 7.4 percent annualized return. He could have realized 7.6 percent by investing in an S&P 500 index fund over the same period.)

Supply and demand set prices, and when it comes to Reynolds, there's a lot of supply. The prolific artist ran an efficient studio and accommodated half a dozen sitters a day. Most of today's billionaires prefer contemporary art. Reynolds' full-figures of run-of-the-mill aristocrats sell for seven figures (or less, sometimes a lot less). The Portrait of Mai was long at Castle Howard, the exterior shot for the Jeremy Irons Brideshead Revisited TV series. Another Castle Howard Reynolds, Portrait of Frederick, 5th Earl of Carlisle, shows the aristocrat who bought Portrait of Mai after the artist's death. In 2016 Frederick's portrait was valued at $6.1 million in lieu of inheritance tax. If that's a fair valuation for a great Reynolds, then the £50 million price for Portrait of Mai is due less to Reynolds than to its subject's resonance with 21st-century museum audiences.

Western museums are striving to diversify their collections with early portraits of persons of color. They have often had to settle for pictures by third-rate artists. An example is a painting bought by LACMA last year. It is believed to be British painter William Armfield Hobday's 1815 portrait of the American-Haitian educator Prince Saunders. Like Mai, Saunders was feted in London. Unlike Reynolds, Hobday was "an exceptionally minor early nineteenth century portrait painter," as Britain's export case hearing for the LACMA picture bluntly puts it. "Hobday's work cannot be said to possess great aesthetic merit."

UK and US media (including The New York Times, see correction) have described Mai as Britain's first painting of a person of color. It's not that. Pocahontas visited England in 1616-1617, and her likeness, in British finery, was recorded in a famous engraving suspected to be based on a lost painting. A surviving Portrait of an African is attributed to Allan Ramsay and dated around 1758. It may depict Ignatius Sancho, a early abolitionist and author. Gainsborough painted Sancho a decade later.

|

| Joshua Reynolds, Portrait of a Man, Probably Francis Barber, about 1770. The Menil Collection, Houston |

A few years after that Reynolds painted a Black man believed to be Francis Barber, Samuel Johnson's Jamaican servant and heir. The painting is lost, but the Menil Collection has a brilliant sketch.

_-_Huang_Ya_Dong_'Wang-Y-Tong'_-_129924_-_National_Trust.jpg) |

| Joshua Reynolds, Portrait of Wang-y-Tong, 1776. Knole, Kent, National Trust |

Reynolds also painted one of the earliest Chinese visitors to Britain, known as Wang-y-Tong. His portrait is a character study reflecting European conceptions of chinoiserie. It may have been made while Reynolds was working on Portrait of Mai.

Portrait of Mai stands apart in scale (full-length and life-size), classicism (the Apollo Belvedere with tats) and apparent sympathy with the subject. The painting was not commissioned, and Reynolds kept it in his studio throughout his life. The portrait is a fiction, as Reynolds' major portraits generally are. Mai wore English clothes in London, and complained they were miserably uncomfortable. Reynolds imagines Mai in a globalizing costume combining toga, turban, and kapa cloth sash. It is the first grand manner portrait of a Pacific Islander, and certainly the first by a British artist of Reynolds' stature.

It's not surprising that Portrait of Mai commanded a premium over a more typical Reynolds. But £50 million still seems high. My reading is that NPG director Nicholas Cullinan really, really wanted this painting and knew that Magnier was a wild card. The tycoon had spurned the Tate Gallery's 2002 offer of £12.5 million. Cullinan offered a price that Magnier would understand to be more than he could likely get on the international market. This secured Magnier's patience and cooperation during a long fund drive.

The NPG would have bought Mai on its own, had the fundraising gods allowed. The Getty was brought in as a partner of last resort. At that, the deal almost fell apart last December, when one of the UK funders, the National Heritage Memorial Fund, objected that the painting should stay on British soil.

The National Heritage Memorial Fund is now on board, and its chair Simon Thurley is among those praising the joint purchase in the Getty/NPG press release. The word innovative appears six times. Historian and NPG trustee Simon Sebag-Montefiore calls the partnership "an innovative deal that itself will be a model for the future." For Timothy Potts, it's "an innovative model that we hope will encourage others to think creatively about how major works of art can most effectively be shared."

(2) Is this innovative model scalable? There are other art-sharing arrangements in the UK, Europe, and greater L.A. (where the Getty and the Norton Simon museum have been time-sharing a Poussin painting and a Degas pastel since the 1980s). Sharing across continents rather than freeways amplifies the risks.

The Getty was thwarted in its bid to acquire Canova's sculptural masterpiece, The Three Graces. The British government repeatedly delayed export, allowing it to be purchased jointly in 1994 by the National Gallery of Scotland and the V&A Museum, London. The sculpture rotates between the two museums. In 1998 a new hairline crack was discovered in the marble. "To be honest, it would have been much safer in the Getty," said Duncan McMillan, director of the University of Edinburgh's gallery.

That's a marble statue that weighs nearly a ton. A closer analogy to Mai is Gainsborough's Blue Boy. In 2022 the Huntington lent Blue Boy to the U.K. National Gallery. There was alarming dissent over the loan's safety, with dueling panels of experts. Blue Boy made it back in one piece.

Sharing is good. In some cases, joint ownership is a no-brainer, as when museums share video or conceptual works that don't entail moving physical objects. For older, more fragile works, sharing comes with risk. The Getty-NPG partnership apparently envisions shipping Mai across the globe ~20 times a century, forever. What happens, should Mai one day be judged too fragile to travel anymore?

The two museums are evidently satisfied that any such eventuality is a long way off. But there are risks any time an artwork is moved. We accept them in order to have loan exhibitions that advance scholarship and to bring art to parts of the world where it's not normally on view.

Say the Yale Center for British Art wanted Mai for an exhibition. Would they get it, even though it might come out of one co-owner's term, and fewer people would see it in New Haven? What if the Tate, Met, and National Gallery of Australia wanted Mai for a Reynolds mega-show touring for multiple years? It would be like holiday arrangements for divorced families. It could be worked out, but it adds a layer of complication that's not there with a single owner/lender.

My sense is that the NPG-Getty deal means Mai will spend a lot of time in London and L.A., but loans elsewhere may be less frequent than they might have been otherwise. There are other ways to share. Nothing prevents a single owner from being super-generous with loans and ensuring that valued artworks are seen throughout the world. That too is a model worth considering.

Comments

Also, European cities like London or Paris have more "bric-a-brac" (valuable or otherwise) than they know what to do with.

Someone doesn't know much about the Yale British Art Center. More people would probably see it in New Haven because the Yale museums draw visitors from New York.

Some points:

Exceptional full lengths by Reynolds have never really been sold on the auction markets for at least 20 years. You had Potrait of Lady Marsham that sold for around GBP 5 Million ( then over USD 8 Million) in 2016 but then this was a good but not an exceptional full length. Yes Portrait of Earl of Carlisle is a brilliant Reynolds and was bought by the UK state in lieu of circa GBP 5Million. But you forget the way this system works. The seller is saving 40 percent UK inheritance tax by relinquishing title to the painting. So the GBP 5Million value is saving 40 percent IHT. To get a "market value" you would have to gross up the value by the balance 60 percent. Which would mean an open market value of well over GBP 10 Million.

Condition of the painting is another variable factor affection price. Omai is in exceptional condition.

Reynolds produced a lot of Portraits and employed a lot of studio assistants. But the Portrais that are painted solely by his hand can be differentiated and are much less. So you had Potrait of the Earl of Hay that sold at Christie's for GBP 150K. But you can see that this is a hugely inferior work.

Say you had an exceptional full length like the Portrait of Lady Worsley come up for sale at one of the major auction houses and the work had an export license I can well believe the auction estimate would be GBP 30 to 50M and that the actual selling price would probably fly well above that level.

The issue is these portraits rarely/never come up for sale.

As in all things there is the best and then the rest!

Admission is free for everyone.

When I went to Yale, the person at the front desk did not count how many times I came and went in the same day. I used the sitting areas in the Yale museums like a reading room.

Thinking back, I can't remember where the front desk was/is at the Yale British Art Center. You do not pass directly in front of it to gain admission. That makes it less likely someone is truly counting visitors who are associated with the University or not part of some tour group.

As an aside, I'm checking out RISD in June.

Reynold also painted the remarkable full length Portrait of the children of Sir Simpson Gideon, 1st Bt. and his wife Maria Yardley Wilmot. The sitters' grandfather, the Portuguese-born financier, Sampson Gideon was the first major Jewish collector of old master pictures in this country, commissioning Isaac Ware to add a Great Room for these to Belvedere, his house in Kent.

This ambitious late work by Reynolds is the earliest swagger portrait of members of a Jewish family by a major British artist.

In 2012 the painting was saved for the nation in lieu of tax of £3.3 million of tax. This was based on a market value of the painting of over £7 million.

It is interesting that this picture came from the Cowdray collection and the then UK government had a choice to accept this Reynolds or Gainsborough's Lady Villebois( from the same collection) in lieu of the tax owed.

The government of course opted for the Reynolds. This picture is allocated to the Barber Institute in the UK which was considered doubly appropriate because Birmingham has long had a significant Jewish community and Broughton Castle, seat of Maria Gideon's husband is less than forty miles away.

The Gainsborough full length of course sold at Christie's in 2012 for about £8 million.

Had the Reynolds been the one sold at auction it is almost certain that it would have achieved much more than the Gainsborough.

Again this illustrates that these important and magnificent Reynolds full lengths are never allowed to be released to the open market. Private buyers are never given access.

Today Portrait of Maria and William Gideon is probably a £50 million plus painting or more! We will never know because it will never be given the opportunity to be tested on the sales market.

This is why Omai is so special and the price fully justified.

You say:

'Let no one take that as proof that art is a great investment. Magnier's profit amounts to a 7.4 percent annualized return. He could have realized 7.6 percent by investing in an S&P 500 index fund over the same period.'

Whilst the above is correct, please also note that Magnier is Irish resident and any gain on stocks would have been taxed at a capital gains tax rate of 15 percent (if held for more than 2 years) and 35 percent (if held for less than 2 years).

Ireland has a special exemption for artwork that is lent to national galleries. As Magnier lent Mai to the National Gallery of Ireland for 6 years his capital gains tax on Mai would be ZERO percent.

On a net back basis Magnier's purchase of Mai has greatly outperformed the S&P 500 index fund over the same period.

What is that they say about the luck of the Irish!?

The only downside for Magnier is that had he been successful in getting an export license and Mai had been put up for sale privately or via auction he most likely would have achieved a price far above $62 million.

As for the Getty it should really be on the lookout to purchase another spectacular full-length Reynolds for when Mai is not in situ.

One thing I've taken with me from my low-rent college days is a professor's constant refrain: "Decision with reasons, please."

I'd love for someone to tell me how this work would fetch USD62M at an unrestricted sale at a major auction house in London or New York.

The reason it would probably reach more than $62M is:

Competition.

The current sale process is completely shrouded in mystery. I understand the initial valuation was done by Christies. This was corroborated by the UK government's valuer Anthony Mould.

But we don't know what metrics were used for valuation. Was the valuation based on Mai being sold freely on the world stage with an export license? Or was it based with the caveat that the export license 'might' not be available.

All commentators go on about the fact that Mai was sold in 2002 for £10M. Sure. But even when Magnier bid for this picture in 2002 he would have known and been advised that it was dead certain that Mai would not receive an export license automatically and have an export ban put on it. So even the result of the 2002 auction is also flawed as it is not fully representative of the scenario of Mai being sold on the world stage with an export license. This scenario has never ever been tested except perhaps hypothetically.

The second thing commentators go on about is how could Omai be worth £10M in 2002 and now after 20 years be worth £50M. Apart from the inflation of the top end of art prices and Reynolds full lengths ( see above comment that an ordinary full length by Reynolds of Lady Marsham sold for £5M at auction at Christie's in 2016) and more interest in non white subjects-perception can change fast in art.

As an example,Reynolds full length 'The Archers' came up for sale at Christie's in 2000. It was dirty and not in good shape. At the auction the estimate was £1.5 to 2.5M. There was only one bidder the Australian billionaire John Schaffer who picked it at the reserve of £1.5M. He had the picture cleaned and restored over one year. When Tate Britain saw it they loved it. There was also a German Museum interested. It sold in 2005 for £3.2M to the Tate. That is the price more than doubled in five years. The point is these things do happen in art commerce and to Reynolds full lengths!

The final point re competition is that the world has changed from 20 years ago. There are bigger buyers with deeper pockets than the Getty. You have the Louvre Abu Dhabi, the Qatari Royals and now the Saudis. What happened to Salvatore Mundi is more likely to happen to Mai. The image of Mai, although Polynesian, with his beautiful Golden brown face and white turban is more Middle Eastern/Turkish/South Asian and orientalist. This is an image that these buyers (who have the deepest pockets in the world) and their audiences can identify with. For them to own perhaps the greatest earliest full length by one of the great 18th century artists of such an image, I believe, would drive the price far above £62M.

Even the campaign to save Mai in the last year has already made it a world famous image. Ironically this campaign has probably actually pushed up its value further.

One thing I am certain is that it is a bargin for the NPG and the Getty. In an interview in the FT the NPG director said the Full power of the Potrait has not been freed. I agree. Mai has never been in a large museum on public show continually. The Getty and NPG have the chance to do this.

And if done correctly in 20 years commentators will laugh at how in 2023 Mai was bought way too much on the cheap!

Always a pleasure Ted!

Getty don't need no more stinkin' Reynoldses!

I just got back from spending five days studying the Saxon State art collections at Dresden. They had been on my to-do list for decades and I never got around to seeing them until now.

At the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister I started with the later paintings (1650-1750 CE) on the upper floor, and I was so impressed and amazed at the quality, breadth and depth of the works on display.

Then I went to the main floor (pre-1650 CE) and I felt like I was struck with cataracts. Masterpiece after masterpiece (Annibale Carracci; Rubens; Raphael; Corregio; Poussin) was so dulled, one could hardly identify the actual colors! Varnish so old, dirty and crusty I could hardly contain my sadness. This place wasn't the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister. It was the Gemäldegalerie _Jaundice_ Meister!

That's why I continuously thought ... Getty, Getty, Getty.

I thought: Getty has a storied conservation infrastructure, among the finest in the world. Why can't Getty stage a Rapid Response Campaign in aid of Dresden? Maybe 50-100 paintings are in dire need of restoration. Dresden could give Getty two or three paintings at a time, and in exchange for Getty's efforts, Getty could keep the works and show them in Los Angeles for 6 months to a year. The relationship would be decades in development.

A win-win.

I think Dresden is waiting for your call.

I lodged my disappointment to a doyenne who was showing the collection to large groups. She said, "money" was the issue.

Getty will never have works of the quality of Dresden's, but they could bring German heritage back to full flower, and enhance California's art scene immeasurably.

My two cents.

I'm so angry I could spit.

These are the full lengths that the great Reynolds scholar E K Waterhouse considered to be among Reynolds best.

looking at the list I think the Getty has no chance of buying another so the previous reader can relax. Its not going to happen.

1. The Hon. Augustus (later Viscount) Keppel (1725-86),

1753-4

National Maritime Museum, UK

2. Peter, 1st Baron (later Earl) Ludlow (1730-1803), 1755

Marquess of Tavistock and the Trustees of the Bedford Estate, at Woburn Abbey, UK

3. Captain Robert Orme ( 1725-90), 1756

National Gallery London, UK

4. James, 7th Earl of Lauderdale (1718-89), 1759-61

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Australia

5. Lady Elizabeth Keppel, Marchioness of Livestock (1739-68), 1762

Marquess of Tavistock and the Trustees of the Bedford Estate, at Woburn Abbey, UK

6. Master Thomas Lister, later 1st Lord Ribblesdale (1752-1826), 1764

Cartwright Hall Art Gallery, UK

7. Philip Gell (1723-95), 1763

Private collection, Henry Chandos-Pole-Gell descendants, UK

8. John, 3rd Earl of Bute (1713-92), and his secretary, Charles Jenkinson (1729-1808), later Earl of Liverpool, 1763

Private collection, Marquess of Bute descendants, UK

9. Lady Sarah Bunbury (1745-1826) sacrificing the Graces, 1764

The Art Institute of Chicago, USA

10. Elizabeth (Widdrington), Mrs Thomas Riddell (1730-96), 1763

Laing Art Gallery and Museum, UK

11. Colonel John Dyke Land (1746-78) and Thomas, Viscount Sydney (1733-1800), 1770

Tate Britain Museum, UK

12. Fredrick 5th Earl of Carlisle, K.T. (1748-1825), 1769

Tate Britain Museum, UK

13. The Hon. Mrs Theresa Parker (1744-75), 1773

Saltram, The National Trust, UK

14. Three Ladies adorning a term of hymen, 1774

Tate Britain Museum, UK

15. Omai, 1776

National Portrait Gallery UK and The Getty Los Angeles USA

16. The Hon. Mary Monckton, later Countess of Cork (1745-1840), 1777

Tate Britain Museum, UK

17. The family of George, 4th Duke of Marlborough, 1778

Blenheim Palace, Duke of Marlborough, UK

18. Lady Worsley, 1780

Harewood House, Earl and Countess of Harewood and the Trustees of the Harewood House Trust, UK

19. John Campbell, 1st Lord Cawdor ( 1753-1821), 1778

Private collection, Earl Cawdor descendants, UK

20. Captain John Hayes St Leger (1756-99), 1778

Waddesdon Manor, The National Trust, UK

21. Lady Jane Halliday (1750-1802), 1779

Waddesdon Manor, The National Trust, UK

22. Mary, Countess of Bute (1718-94), 1779

Private collection, Marquess of Bute descendants, UK

23. Mrs Pelham (1752-86), 1774

Private collection, Earl of Yarborough descendants, UK

24. Jane Fleming, Countess of Harrington (1755-1824), 1779

Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery, USA

25. Mrs Emily Pott (d. 1782), 1781

Waddesdon Manor, The National Trust, UK

26. Sarah Siddons (1755-1831) as the Tragic Muse, 1784

Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery, USA

27. Lieutenant-Colonel (Sir) Banastre Tarleton (1754-1833), 1782

National Gallery London, UK

28. Charles, 3rd Earl of Harrington (1753-1829), 1783

Yale Centre for British Art, Yale University, USA

29. George IV (1762-1830), when Prince of Wales, 1787

Arundel Castle, Duke of Norfolk, UK

30. George IV (1762-1830), when Prince of Wales, 1784

Lord Andrew Lloyd-Webber Art Collection, UK

31. Colonel (later General) George Morgan (1740-1823), 1788

The National Museum of Wales, UK

32. The Lamb family, 1785

Firle Place, Viscount Gage, Trustees of The Firle Estate Settlement, UK

33. The Cottagers, Mrs and Miss Macklin and Miss Potts, 1788

The Detroit Institute of Arts, USA

34. Admiral Lord Rodney (1719-92), 1789

Royal Collection Trusts, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, UK

35. Francis Lord Rawdon, later Marquess of Hastings (1754-1825), 1790

Royal Collection Trusts, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, UK

36. Lady Amabel Yorke, later Baroness Lucas (1751-1833) and Lady Mary Jemima Yorke (1756-1830), 1760

The Cleveland Museum of Art, USA

37. The children of Edward Holden Cruttenden, 1759

Sao Paulo Museum of Art, Brazil

38. Four children of the 2nd Viscount Grimston, 1767

Gorhambury, Earl of Verulam, UK

The above works are from Ellis Waterhouse's anthology Reynolds (1973). Here Waterhouse acts a curator of a Musée imaginaire and selects those full lengths (and other smaller works) which he considered to be among Reynolds best. I don't think he ranked the full lengths in any particular order of preference.

Regarding no. 28 on the Waterhouse list, Charles, 3rd Earl of Harrington, owned by Yale Center.

Yale has retitled this masterpiece quite rightly to include the identity of the child in the picture, now known to be Marcus Richard Fitzroy Thomas (ca. 1768–1816). According to Yale website,this marks the first time in the painting’s 240-year exhibition history that both figures are named.

Fascinating write up on site:

https://britishart.yale.edu/naming-marcus

Apart from Mai being a hugely important picture for the Getty, the Waterhouse list would have also played a part in its decision to acquire this specific masterpiece.

Waterhouse was the doyen of all Reynolds scholars and a brilliant art historian which the Getty institution had always highly venerated.

After his death in 1985, Waterhouse's wife sold his large library and annotated photographs to help in the initial formation of the Getty Research institute.

The Getty would have anyway always had on its wish list a Reynolds full length from the Waterhouse list.

That it took so very long to acquire one demonstrates how difficult it is to buy the best of Reynolds.

Just saw this.

I don't know about rankings re Waterhouse's list of the 38 of the finest Reynolds full lengths

But, in my humble opinion. the BEST full lengths Portraits and my 5 favourites from the 38 are:

Portrait of Captain Robert Orme-Stunning!

Portrait of Philip Gell-a truly lovely quintessentially English picture!

Portrait of 5th Earl of Carlisle-Gorgeous composition!

Portrait of Family of 4th Duke of Marlborough-Majestic!

Portrait of Lady Worsley-beautiful lady in Red!

Sadly I do NOT think Omai to be Reynolds best or even in the TOP 5.

My late 10 cents for what it's worth!

This is not a full length, nor a masterpiece by any standards. And while Sir Thomas Lawrence is a good English portrait painter, he is my no means anywhere near the standing of Sir Joshua Reynolds in a the history of British Art or for that matter Western art.

So 50 million pounds for a full length masterpiece of a POC by the great Sir Joshua Reynolds seems fully justifiable. It actually looks more like a good deal for the Getty and NPG than Magnier.