|

| Hughie Lee-Smith, Pumping Station, 1960 |

The Hammer Museum's "Joan Didion: What She Means" is an art exhibition about a literary figure, curated by another writer, Hilton Als. The artists on view are Didion's bicoastal contemporaries, though the show is more of a rebus than a visual biography. The lone figure in Hughie Lee-Smith's

Pumping Station could be Didion, though of course she's not.

Didion self-diagnosed an "obsessive interest… in the movement of water through aqueducts and siphons and pumps." There's a great Wayne Thiebaud painting imagining Western hydrology as cake frosting. Didion and Thiebaud died two days apart, the latter in Sacramento, where Didion was born. The show invites you to find your own connections.

|

| Wayne Thiebaud, River Intersection, 2010. Crocker Art Museum |

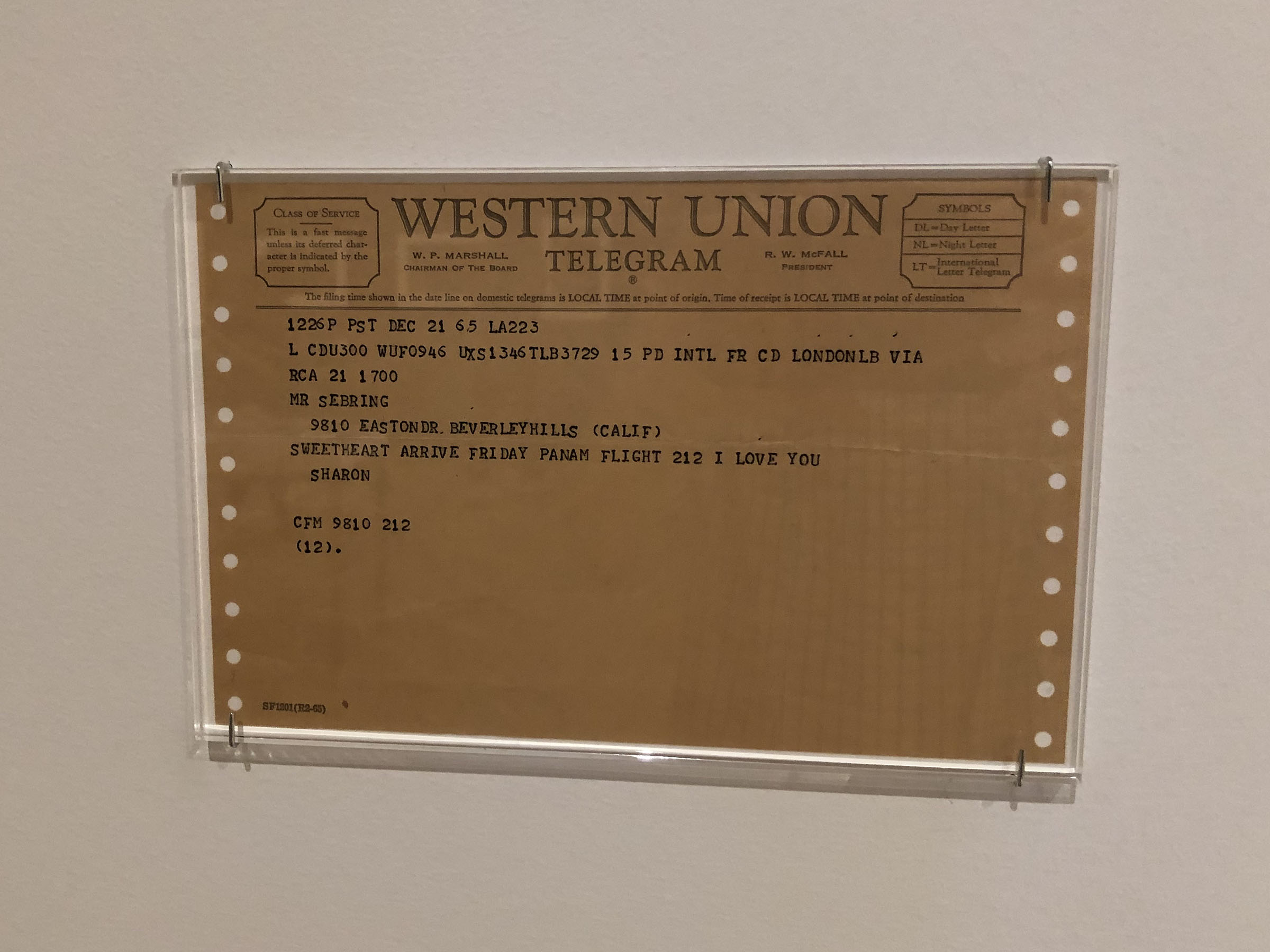

Even in a smart university museum, a show like this raises the question: What if you don't know who Joan Didion is? To some extent the exhibition doubles as a user-friendly introduction to Didion's work. Choice quotes from Didion's oeuvre are printed on the walls in large type. If you're a Didion fanperson-to-be, you'll find out soon enough.

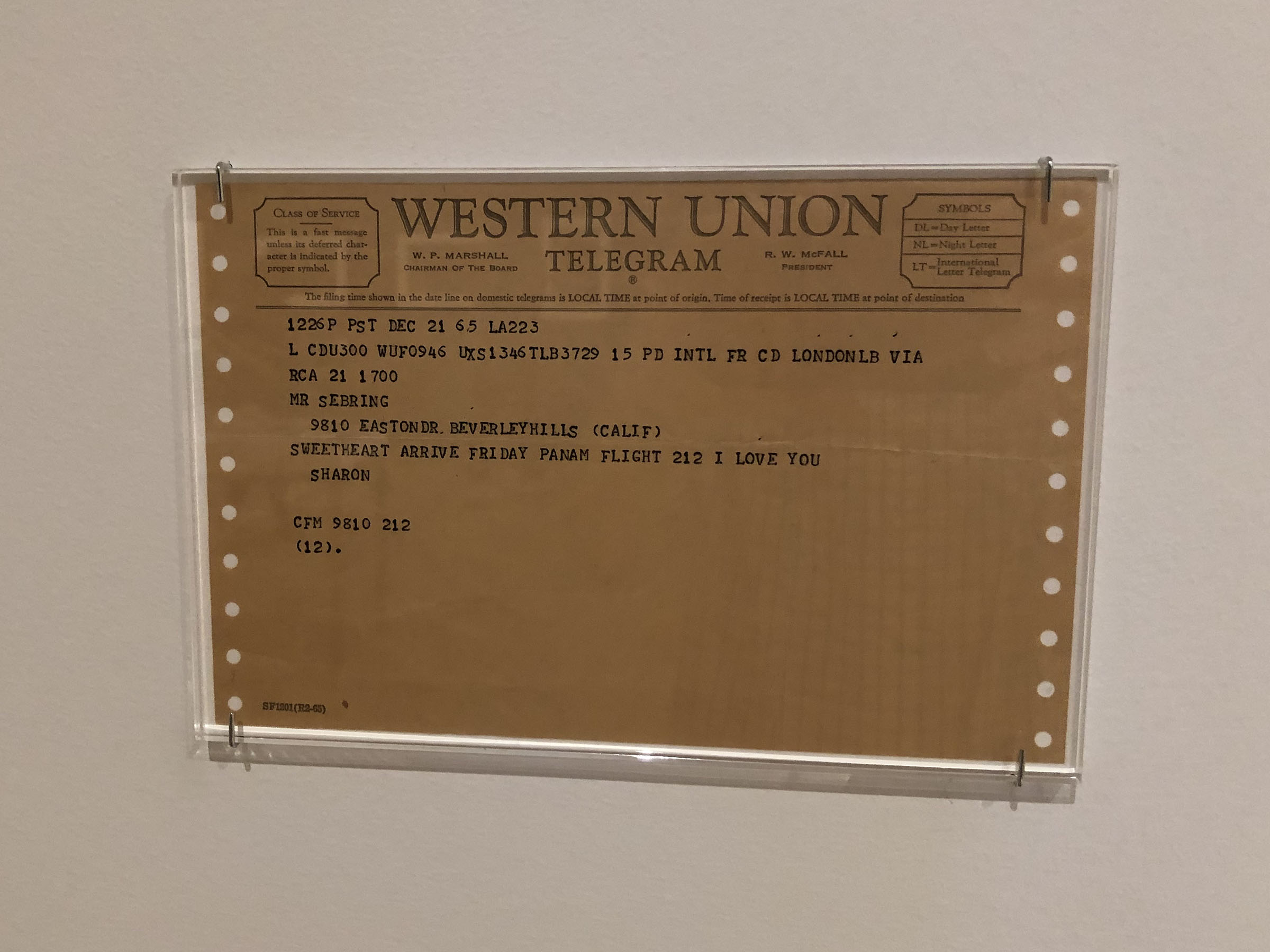

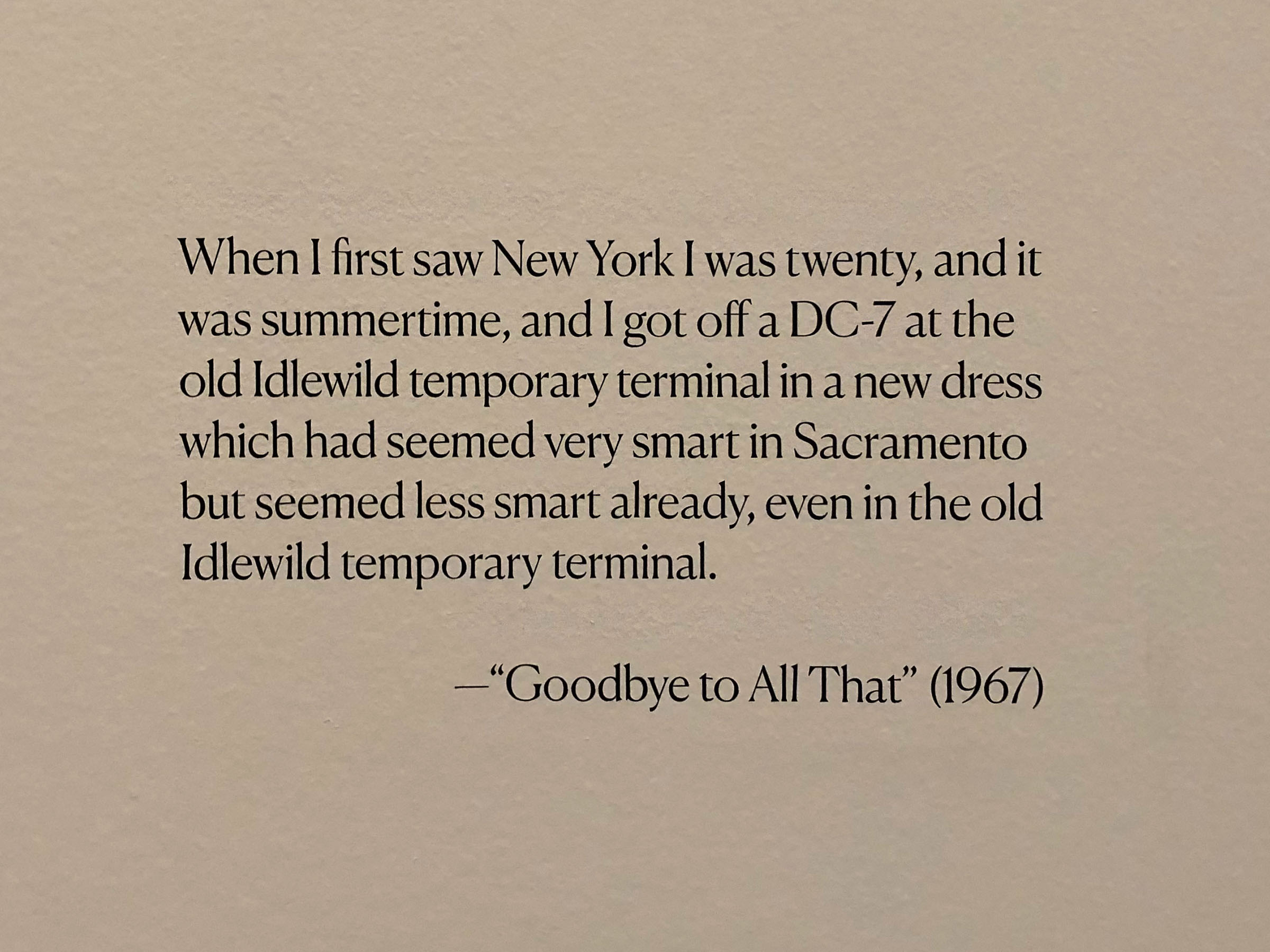

There are the obligatory manuscripts, magazines, first editions, screenplays, and movie posters that you might see in an author show at the Huntington or Morgan. More amusing is a hagiographic assembly of relics from Didion's life, from the family's wooden potato masher to Joan's father's business sign in Sacramento.

The corner installation of the sign echoes that of a brand-new Barbara Bloom piece paying posthumous homage to Didion.

|

| Barbara Bloom, Didion Corner, Captioned, 2022 |

|

| Helen Lundeberg, Studio—Afternoon, 1958-1959. Long Beach Museum of Art |

|

| Vija Celmins, Gun with Hand #1, 1964. Museum of Modern Art |

|

| Diane Arbus, Screaming Woman with Blood on Her Hands, 1961. Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|

| Sharon Tate telegram, sent Dec. 21, 1965 |

|

| Cady Noland, SLA Group Shot #4, 1990. MOCA |

|

| Installation view with Maren Hassinger's River, 1972/2011, in foreground. The Studio Museum in Harlem |

Many of the show's high points are by woman and Watts-era assemblage artists (Hassinger, Saar, Outterbridge, Purifoy). This may cast Didion as more woke than she was. She voted for Barry Goldwater, truly admired John Wayne (referenced here in clips from John Ford's

Stagecoach), and wrote bitterly skeptical pieces on the Black Panthers and Haight-Ashbury hippies. Her most famous comment on the burning of Watts connects it to the Santa Ana winds.

|

| Noah Purifoy, Watts Uprising Remains, 1965-1966. Private collection. Photo: Karl Puchlik |

So is Didion the bard of Hollywood high life… the 60s aftermath… Western water and power… gunslinger Americana… or one of the great post-Algonquin, pre-TikTok wits? This is a show that is certain to extend that conversation. "Joan Didion: What She Means" runs through Jan. 22, 2023. No travel plans have been announced, but a

catalog is to be published next month.

|

| John Koch, Portrait of Dora in Interior, about 1957. Whitney Museum of American Art |

|

| Ben Sakoguchi, Domestic, no date. Hammer Museum |

Comments

> through aqueducts and siphons and pumps."

That reminds me of what I read yesterday about Anne Windsor (aka Princess Anne, daughter of the UK's late monarch). She has a long-time fascination with lighthouses.

https://www.express.co.uk/news/royal/1213532/Princess-Anne-latest-royal-news-lighthouses

Lovelovelove Thiebaud's River Intersection of 2010.

Pity she was a right-wing politico. Hopper was, too.