The Broad Raids the Vault

|

| These three Basquiat paintings, worth $1 bazillion, are owned by the Broad and have never been shown until now |

One of Eli Broad's favorite talking points was that museums keep too much art in their storerooms. He claimed that was why he didn't give his collection to MoMA or LACMA; why he built his own museum o Grand Ave. But of course the Broad (like every other museum) isn't nearly big enough to keep all its art on permanent view. That fact gains ironic perspective at the reopened Broad in a quartet of permanent collection installations celebrating artists held in depth: Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Kara Walker. In each case they're showing all or nearly all the collection's unique works held by the artist. Close to half the objects are being shown at the Broad for the first time ever.

|

| Andy Warhol, Liz [Early Colored Liz], 1963 |

That includes several expensive new acquisitions, headed by a prime Warhol Liz Taylor, a 1973 deconstruction of trompe l'oeil by Lichtenstein, and a big, portentous Walker triptych on paper, The White Power 'Gin/Machine to Harvest the Nativist Instinct for Beneficial Uses to Border Crossers Everywhere (2019), created before the calamities of 2020 and 2021.

|

| Kara Walker, The White Power 'Gin/Machine to Harvest the Nativist Instinct for Beneficial Uses to Border Crossers Everywhere (detail, 2019). Also part of the piece is a group of smaller drawings |

The Broad collection differs from typical public collections in that almost everything is a good-to-great example of some phase of an artist's work. Thus the median quality level of the expanded displays is still high. This may be most evident in the Lichtenstein display, the largest, spanning three rooms and 22 works.

|

| Roy Lichtenstein, Entablature, 1976 |

|

| Jean-Michel Basquiat, Wicker, 1984 |

The Basquiat installation has the smallest ratio of never-shown to shown, 3:10. One of the three is unresolved (Deaf), another is small (Santos 2), and the third (Wicker) is the sort of thing any mid-size public museum would kill for. All are from the early 1980s, the peak of the artist's career.

|

| Susan Rothenberg, Green Studio, 2002-2003 |

Off menu is a one-room grouping of paintings by Susan Rothenberg, who died last year. It has a Green Studio, an ambitious inversion of Matisse I've never seen before.

So why do museums keep so much significant art in storage? It comes down to a topic that Eli knew well, real estate. There is far more museum-worthy art than there is museum space to show it. No, that doesn't mean we need to build more and bigger museums. Real estate is expensive, and so is maintaining it and paying curators decent wages (there's never enough money for that).

There's little point in building much bigger museums unless they draw much bigger audiences. Museum building is limited by the public's large but ultimately finite interest in museum going.

The upshot is that most art owned by museums has to be in storage most of the time. That's a simple reality, not a problem that needs to be solved.

|

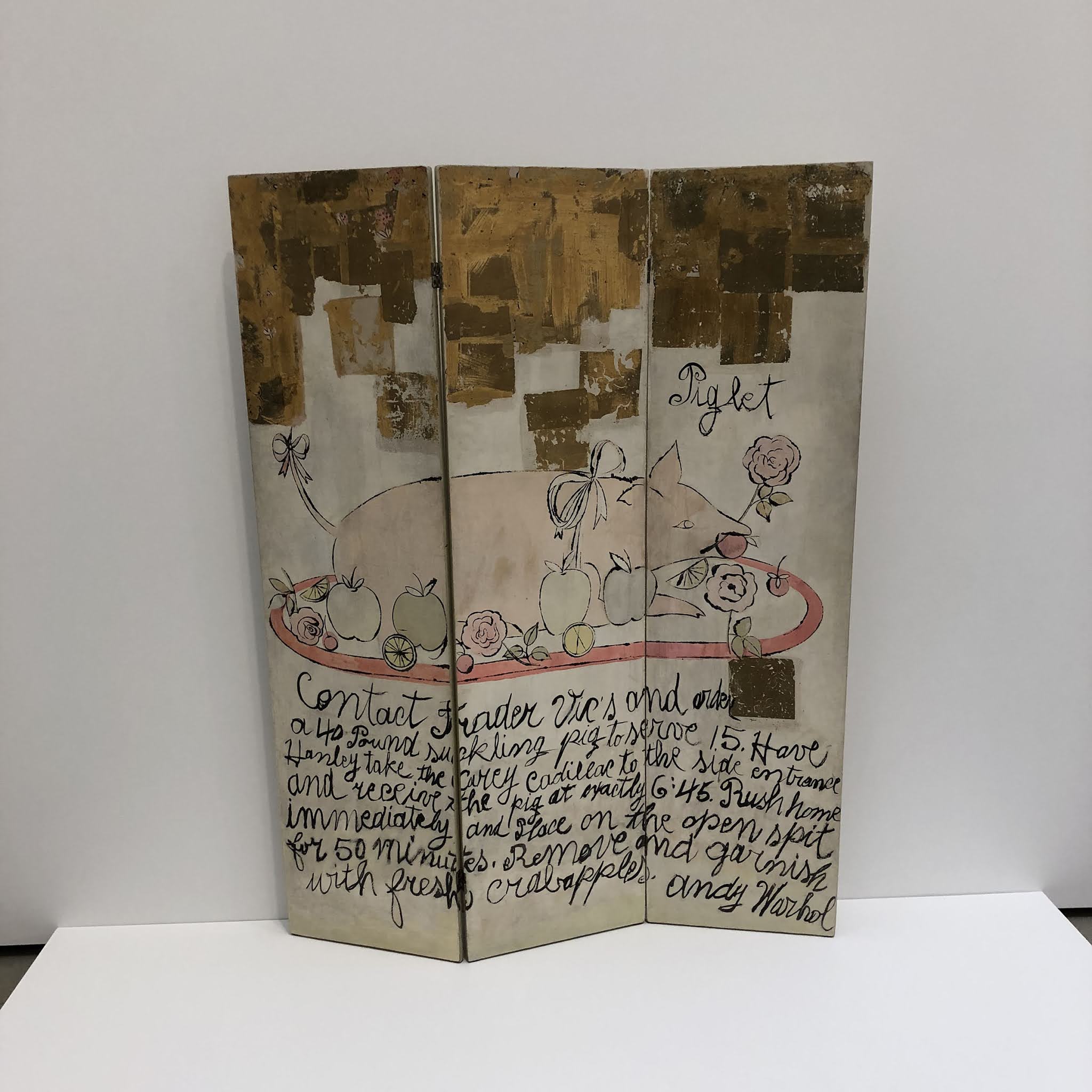

| Andy Warhol, Folding Screen (Piglet), 1955-1957. The Broad owns several 1950s works dating from Warhol's career as a commercial illustrator |

|

| Andy Warhol, Mao, 1973 |

Comments

There's now also that unfinished commercial development across from the concert hall and the rising Lucas Museum a few miles away.

With Andy Warhol's picture of Mao Tse-tung in mind, such entities, including MOCA across the street, will hopefully survive America's own ongoing version of China's Cultural Revolution.