|

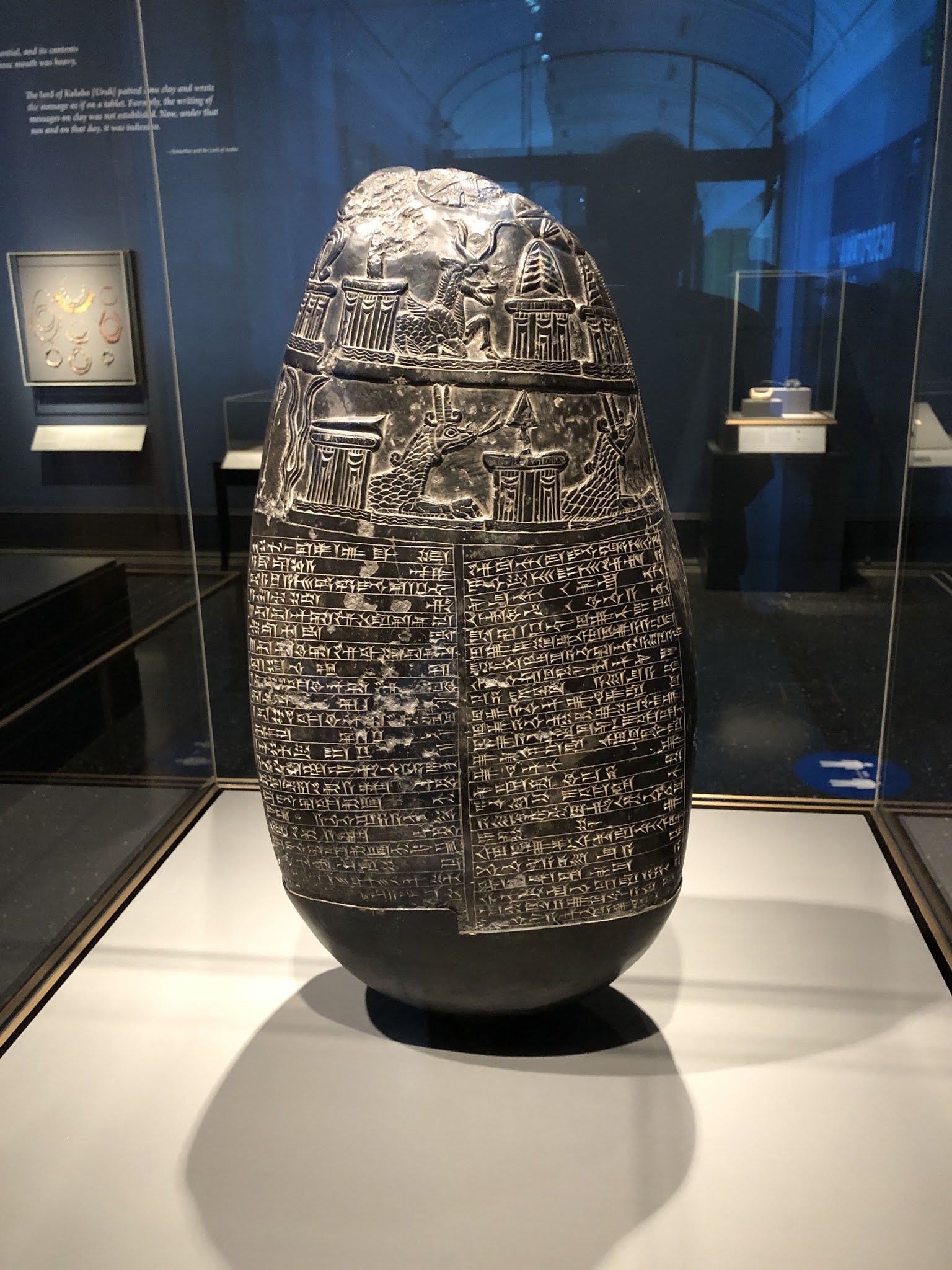

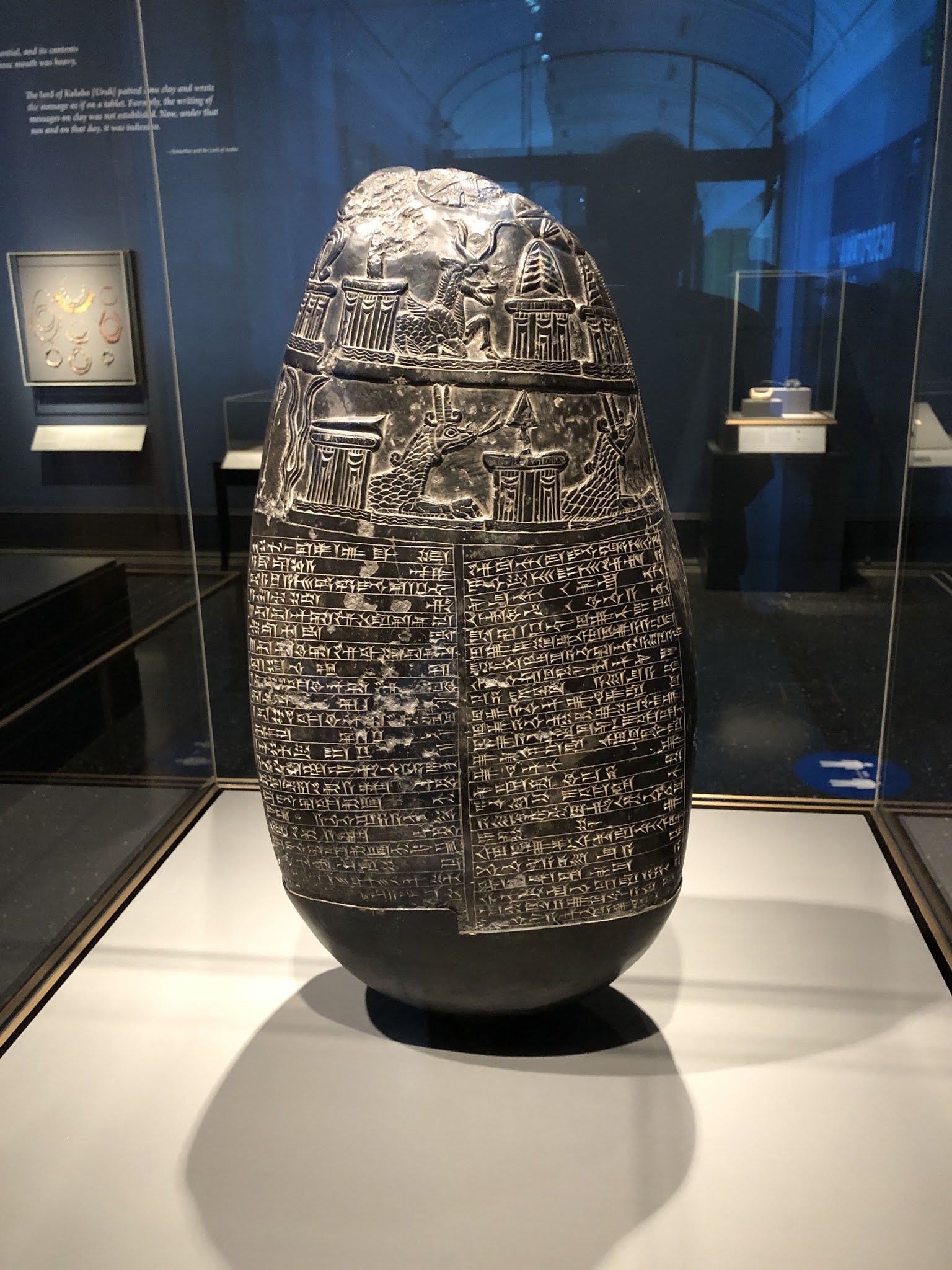

| Land Grant Stele ("Caillou Michaux"), 1100-1083 BC. Bibliothéque nationale de France. |

The Getty Villa is reopening Apr. 21 with "Mesopotamia: Civilization Begins." It's billed as the "most important exhibition of Mesopotamian art ever assembled on the West Coast." To be honest, there hasn't been a whole lot of competition. Most of the objects are from the Louvre. They constitute a choice sampling of that collection's transportable objects, many of them well-known. The exhibition covers a staggering 3000 years of art history, greater than the span from Phidias to Beeple.

Mesopotamia invented cities, and with them, the infrastructure for strangers to coexist in proximity and relative harmony. Objects and labels at the Villa trace the origins of big government and big data; science and social justice; portraiture and poetry. There are magnificent works aplenty, but it's also a show where modest objects tell stories.

There is a small cuneiform tablet of a hymn by Enheduanna (about 2300 BC), celebrated as the first author known by name. Enheduanna, a woman, lived about 1400 years before the Greek poet Homer assuming that Homer was even a real person.

Thanks to the invention of cuneiform writing we know more about the lives of Mesopotamians, ordinary and royal, than is true of many later cultures. Cuneiform text looks spectacular, even when it's legalese boilerplate, as in the Land Grant Stele at top of post. It was a land deed conveying a marriage gift of property to the bride.

|

| Cylinder Seal of the Royal Scribe Ibni-Sharrum, 2217-2193 BC. Louvre. Image © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY. Photo: Franck Raux |

Carved cylinder seals were rolled onto clay to sign a cuneiform tablet. They were a status object, like smartphones or handbags. As relief sculptures in miniature, executed in rare stones, cylinder seals include some of the most inventive and accomplished works of the ancient Middle East. They nonetheless pose a challenge to museum display. It is all but impossible to read tiny negative reliefs on a cylindrical surface only half visible. At the Getty pinpoint lights reveal the seals as the gems they are, but blown-up photos of modern impressions—reproductions twice removed from the original— are essential to appreciate the imagery. Of course, the seal reliefs were made to be seen in reproduction, as clay impressions.

|

| Installation view with Statue of Prince Gudea as Architect (on platform at right), about 2120 BC. |

|

| Head of Prince Gudea, about 2120 BC. Louvre. Image © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY. Photo: Franck Raux

|

Gudea is the most recognizable of Mesopotamian faces. As part of his personal brand-making the ruler of Lagash encouraged sculptural likenesses, and over two dozen are now known. Gudea probably didn't expect that, 41 centuries down the line, his hat would be more recognizable than his blandly sculptured features. The trademark hat, evoking a shtreimel or energy dome, was probably made of wool.

"Mesopotamia" has several Gudea portraits, including two outliers: a standing

Prince Gudea with a Vase of Flowing Water and a seated

Prince Gudea as Architect (both about 2120 BC). The latter has lost its head but, as with other examples, the most expressive part might be the clasped hands. Today the hands read as anxious or calculating. They actually represent a prayer.

|

| Statuette of a Human-Headed Bull, 2140-2000 BC. Louvre. Image © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY. Photo: Hervé Lewandowski

|

Being city folk did not preclude an interest in the natural world. A bestiary of Mesopotamian animals includes supernatural hybrids such as this human-headed bull, a relation to the monumental lamassu statues at the Louvre and elsewhere. Few pack the expressive punch of this fist-sized statuette. (Want a

big lamassu?

Try the Citadel.)

Comments

Nice to also see some normalcy returning to the world of culture, economics and socialization. Even more so when LA's cultural scene has taken a big hit because of the loss of its publicly owned (supposedly) museum devoted to the visual arts.

Then again, people and entities like Anna Bing Arnold or the Ahmanson Foundation were white-supremacist elitists who donated a lot of junk. Grrr.