|

| Édouard Antoine Renard, A Slave Rebellion on a Slave Ship, 1833 |

Slavery is almost invisible in Western art. That changed only in postmodern times as contemporary Black artists took up the theme and scholars renewed interest in the relatively rare historic depictions of slavery and emancipation. The post-1960s contemporary and pre-1888 historical define the chronology of "Afro-Atlantic Histories," an international traveling exhibition now at LACMA for an unusually long run, through Sep. 10, 2023. It's a show with zeitgeist resonance, star-power objects, and surprises at every turn.

|

| Abdias Nascimento, Exu Dambalah, 1973 |

Start with Brazil, as the exhibition itself did. The Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand and the Instituto Tomie Ohtake organized the show in 2018. The former is São Paulo's main art museum; the latter is named for famous-in-Brazil artist Tomie Ohtake and functions as a modern-contemporary kunsthalle. Though the exhibition has gone through nips and tucks on its U.S. tour, the LACMA version incorporates numerous works by Brazilian artists rarely seen here.

Abdias Nascimento was not only a painter but a poet, playwright, scholar, activist, and politician. Exu Dambalah is a lyrical synthesis of African orishas and Latin-American constructivism.

|

| Emanoel Araújo, O Navio (The Ship), 2007. Painted wood and carbon steel. Museu de Arte de Sao Paulo Assis Chateaubriand |

In O Navio (The Ship), Brazilian artist Emanoel Araújo conjoins slave ship diagrams with African wood sculpture, scarification patterns, and globalized modernism. Araújo, who died last September, founded São

Paulo's Museu Afro Brasil. |

| Frans Post, Landscape with Anteater, about 1660. Museu de Art de Sao Paulo Assis Chateaubriand |

An associate of Hals, Dutch painter Frans Post spent seven years in Brazil (1637-1644). Upon returning to Holland, he built a career on re-imagined Brazilian landscapes. He was one of the few European painters to regularly depict slavery, though Post's captives

function as staffage for a New World Arcadia.

|

| Eugène Delacroix, Portrait of a Woman in a Blue Turban, 1827. Dallas Museum of Art |

|

| Frederic Bazille, Young Woman with Peonies, 1870. National Gallery of Art |

Bazille and other struggling Impressionists lived in a Parisian district favored by Black emigres from the French colonies. |

| Nathaniel Jocelyn, Portrait of Cinqué, 1839. Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis |

In 1839 the Africans of the Spanish slave ship La Amistad ("Friendship") rebelled, led by Joseph Cinqué of Sierra Leone. The Africans were not seafarers and did not know how to navigate the ship that had abducted them. Intending to return to West Africa, they went ashore near Long Island and were tried for murder in Connecticut. The U.S. Supreme Court acquitted them. The case galvanized abolitionist sentiment as well as inspiring works of art, literature (Melville's "Benito Cereno"), and film. Nathaniel Jocelyn, a Connecticut abolitionist and painter, portrayed Cinqué through the lens of the Enlightenment—a "noble savage" but also, apparently, an American hero.

|

| Aaron Douglas, Into Bondage, 1936. National Gallery of Art |

|

| Melvin Edwards, Palmares, 1988. Museu de Arte de Sao Paulo Assis Chateaubriand |

|

| Dalton Paula, Zeferina and João de Deus Nascimento, 2018. Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand |

The names but not the likenesses of two leaders of Brazilian slave rebellions—Zeferina and

Joã

o de Deus Nascimento—are recorded. Dalton Paula commemorates them in these imaginary portraits.  |

| Horace Pippin, School Studies, 1944. National Gallery of Art |

A large slice of the exhibition consists of modern and contemporary portrayals of the African diaspora. There is considerable overlap with

LACMA's "Black American Portraits" from only last year. Nevertheless, first-rate works by Jacob Lawrence, Beauford Delaney, Horace Pippin, Romare Beardon, Charles White, Clementine Hunter, and Barkley Hendricks justify the semi-redundancy.  |

| Hayward Oubre, untitled, 1950. The Johnson Collection, Spartanburg, South Carolina |

|

| Alma Thomas, March on Washington, 1964. Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery |

Otherwise DC's great abstractionist, Alma Thomas did this painting of Martin Luther King's 1963 march on Washington. |

| Osmond Watson, Johnny Cool, 1967. National Gallery of Jamaica |

|

| David C. Driskell, Current Forms: Yoruba Circle, 1969. National Gallery of Art |

|

| Barrington Watson, Conversation, 1981. National Gallery of Jamaica |

|

| Clementine Hunter, Black Jesus, about 1985. Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture |

|

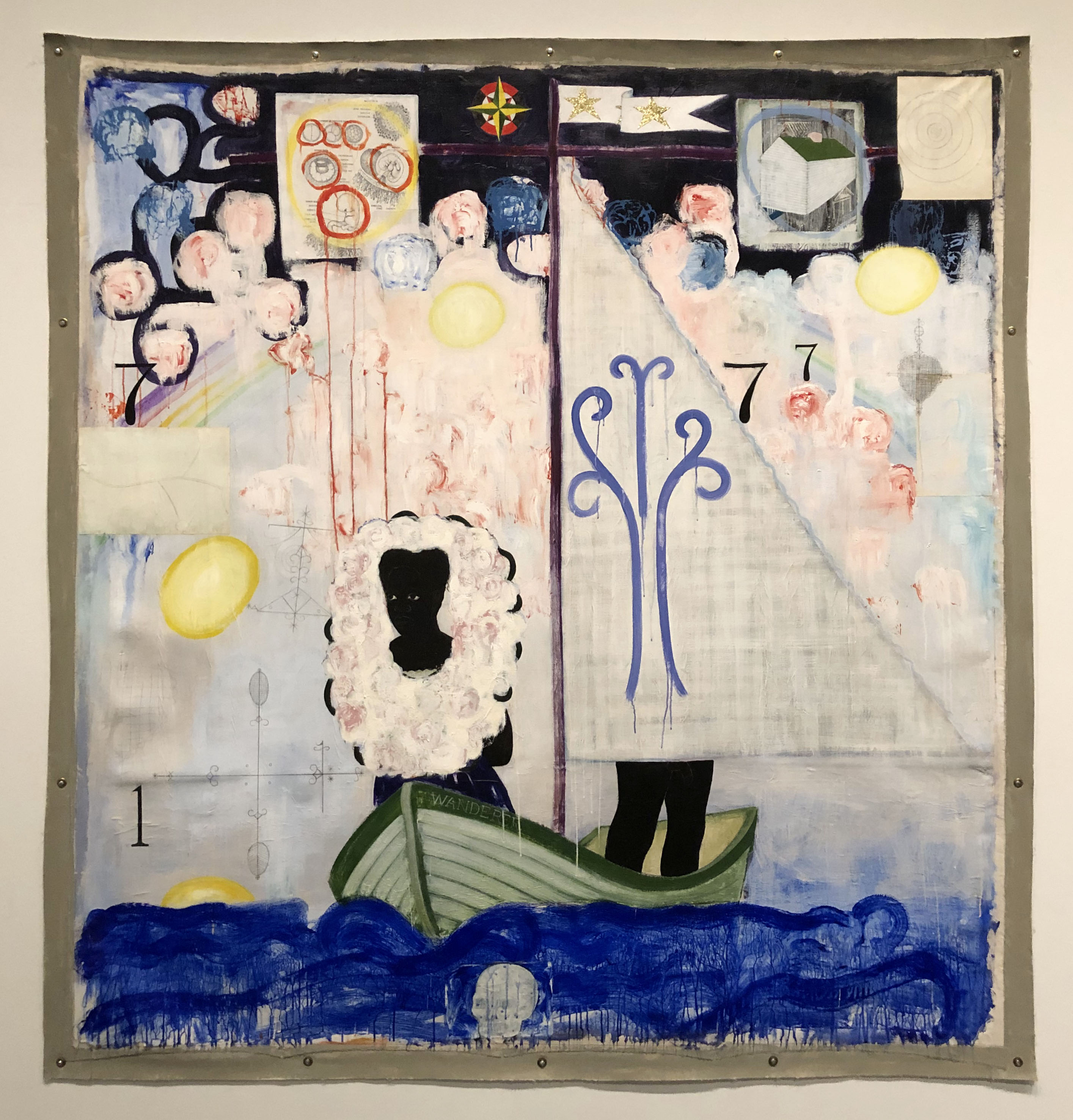

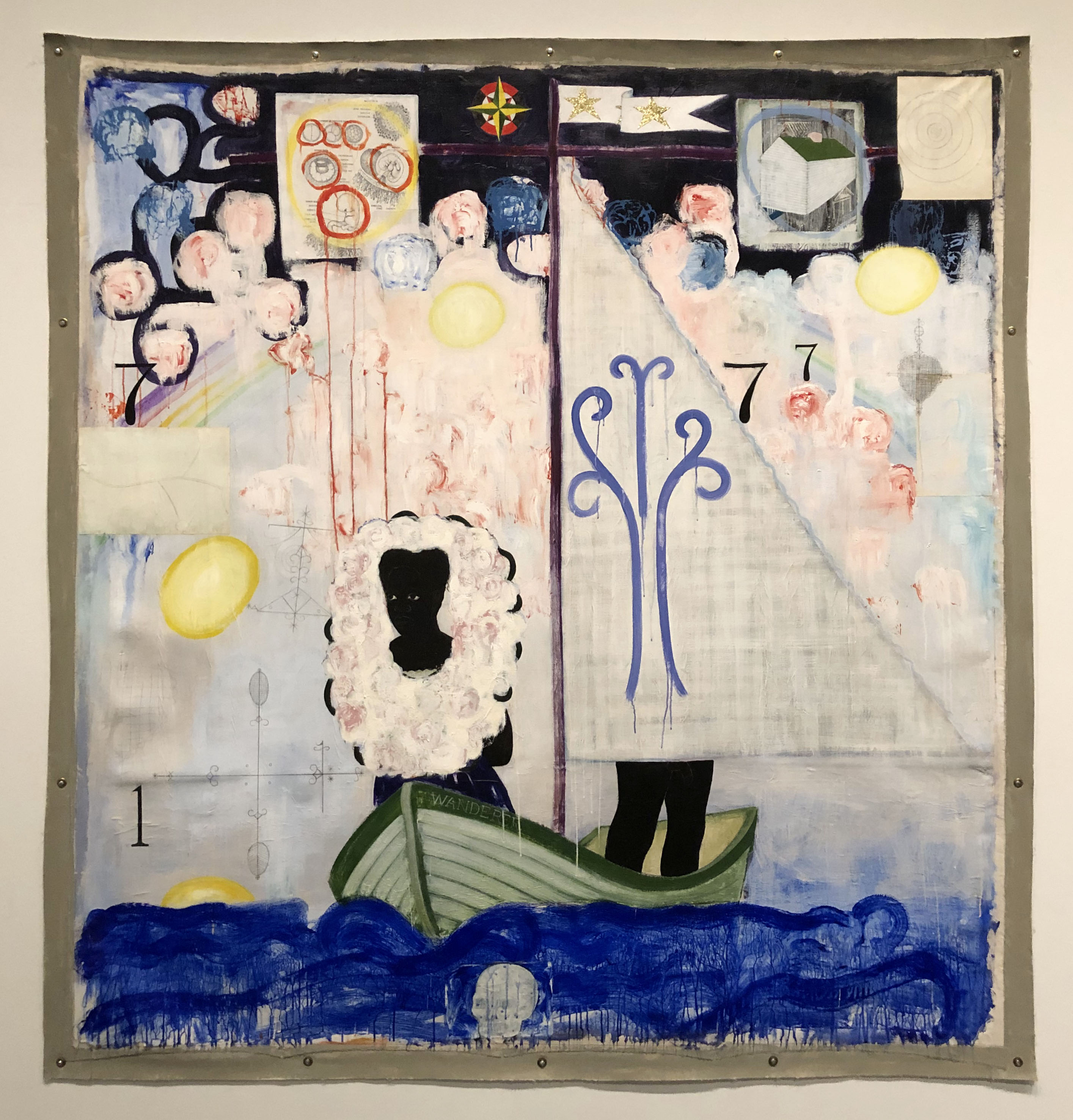

| Kerry James Marshall, Voyager, 1992. National Gallery of Art |

Comments

Do a search for "slavery" on the Met website. There are 182 works listed. No doubt there is vastly more art heritage on slavery at the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History & Culture, to name but one further venue.

One Met work is particularly interesting to me: a ca. 1964 chess set in bronze, titled "Chessgame: Liberty versus Slavery," designed by Alfred Van Loen (1924–1993, American, born Germany).

Following is a list of the cast pieces:

Dimensions:

a) Joy-Tenderness H. 6 3/16 in.

b) Play-Security H. 5 5/8 in.

c) The Scholar H. 7 5/8 in.

d) The United Family H. 10 7/8 in.

e) Peace-Freedom H. 9 3/4 in.

f) Laborer H. 7 5/8 in.

g) Game-Confidence H. 5 3/4 in.

h) Pride-Protection H. 6 in.

i) Drummer H. 4 1/16 in.

j) Clarinetist H. 5 3/4 in.

k) Cellist H. 4 3/4 in.

l) Accordionist H. 4 1/2 in.

m) Cymbal Player H. 4 1/2 in.

n) Guitarist H. 4 11/16 in.

o) Harpist H. 4 in.

p) Violinist H. 4 5/16 in.

aa) Bondage H. 5 5/16 in.

bb) Strangulation H. 5 7/8 in.

cc) Hurt Helpless H. 7 in.

dd) Prisoner-Imprisoned H. 10 1/4 in.

ee) Nurse-Pity H. 8 5/8 in.

ff) Hopeless-Damaged H. 7 in.

gg) Brutality-Cruelty H. 6 1/4 in.

hh) Chained H. 5 in.

ii) Wounded H. 4 1/4 in.

jj) Sick H. 4 9/16 in.

kk) Crushed H. 4 3/8 in.

ll) Hopeless H. 4 7/16 in.

mm) Beggar H. 3 15/16 in.

nn) Despair H. 4 5/16 in.

oo) Cripple H. 4 9/16 in.

pp) Blind H. 4 5/16 in.

EVERYTHING is filtered through the social, cultural, political lens of a person.

"You say tomato, I say tomahto."

Look at how medicine and medical treatments over the past 2.5 years have been very politicized. In general, the gatekeepers of EVERYTHING - in the field of arts, culture, education, athletics, government, economics, etc - are affected by what's known as influencers, pecking order and normalcy bias.

The future Lucas museum ("treacle") is going to be another example of that. The future LACMA building ("concrete overpass with floor-to-ceiling windows") will be an additional case of that.

As for some of the images posted for the "Afro-Atlantic" blog entry? They're examples of hidden talent existing out there. So who gets the most attention - or is generally ignored - is very much dependent on the gatekeepers of culture, history, politics and economics.

https://news.artnet.com/art-world/art-industry-news-social-media-users-lambast-hank-willis-thomass-insulting-martin-luther-king-monument-other-stories-2243215

Hank Willis Thomas’s Martin Luther King Jr.

Monument – The artist’s sculpture in Boston

has become the subject of unflattering

comparisons. Featuring the disembodied arms

of the civil rights leader in an embrace

with his wife, Coretta Scott King, a fair

number of Twitter users—and at least one

relative of the Kings’s—think it looks

like a turd, or worse, a phallus. The

“insulting” artwork “looks more like a

pair of hands hugging a beefy penis than

a special moment shared by the iconic

couple”...

^ As with the new LACMA overpass, I bet that sculpture eventually becomes a major selfie or Instagram moment.

Actually, the criticism of Hank Thomas's sculpture comes from what likely are mainly self-identifying progressives or leftists - or apolitical types - whereas I believe QAnon is associated with mainly conservatives or rightwingers.

By contrast, I appreciate your succinct list, dimensions and all.

If you are criticizing the politicization of art, it's mainly a conservative or rightwing position.

Because what the QAnon art critic is really saying is that when "white" men were the ones making the art, there were more eternal standards and art was not political. That's bull shit. The Railway is a political painting. The Death of Socrates is a political painting. Las Meninas is a political painting.

But hey, if you want to ignore all that to make a convenient point about the Hank Thomas controversy, I hear the MAGA Newsletter and KKK Times are looking for an art critic. By all means, apply...

https://www.nytimes.com/1977/09/22/archives/selective-compassion.html

> The most striking example of selective compassion

> was Hitler. He was a vegetarian and opposed

> vivisection of animals.

Those paintings ask us to take a side --- the side of the child or the train; the side of Socrates or the side of Plato; the side of the painter or that of the King.

The politics of the painting is embedded in the composition. It's unavoidable.

--- J. Garcin