|

| Käthe Kollwitz, Frontal Self-Portrait, 1922-23. Museum of Modern Art |

Not many Westerners know of the significance of Käthe Kollwitz's work to Chinese modernism. In the early 1930s, poet and activist Lu Xun championed Kollwitz's woodcut prints to Chinese artists. This led to a vogue for the woodcut medium in mid-century China. Kollwitz's social justice concerns resonated, and Mao's 1942 speech at the Yan'an Forum on Literature and Art gave woodcuts an official imprimatur. The People's Republic adopted the medium for propaganda. Kollwitz-style angst gave way to beatific views of a workers' utopia. More recently woodcuts have been repurposed to critique the Chinese state.

USC's Pacific Asia Museum has a survey of contemporary Chinese printed pictures in "Imprinting in Time—Chinese Printmaking at the Beginning of a New Era" (through Nov. 12, 2023). It covers the period from about 1980 to the present, showing a varieties of techniques and politics. The works are drawn from the Charles T. Townley collection, donated to the museum over the past few years. In recent decades the museum's exhibition program has emphasized contemporary art. Townley's collection (which also includes contemporary paintings and sculptures) is a significant boost in that direction.

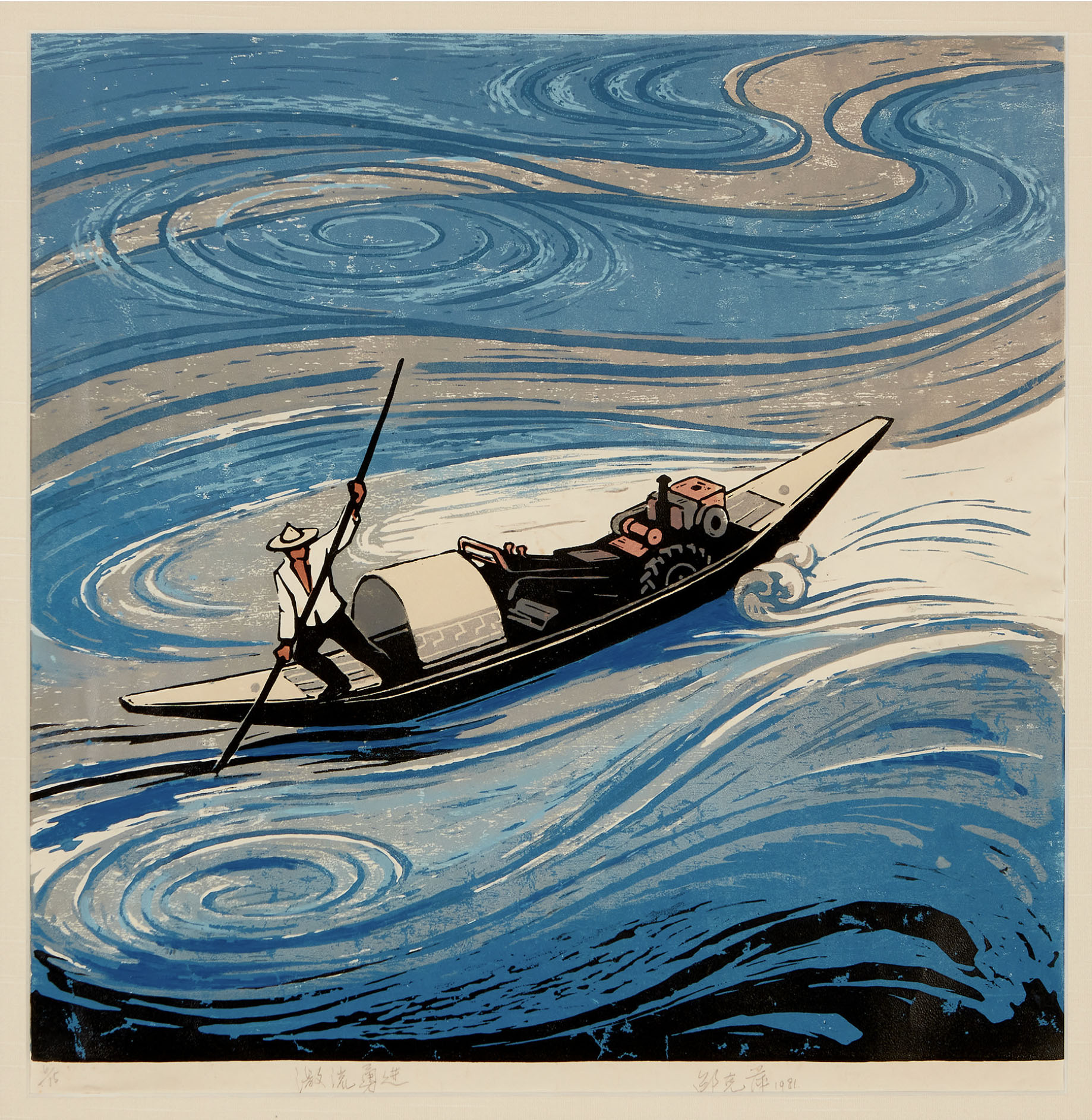

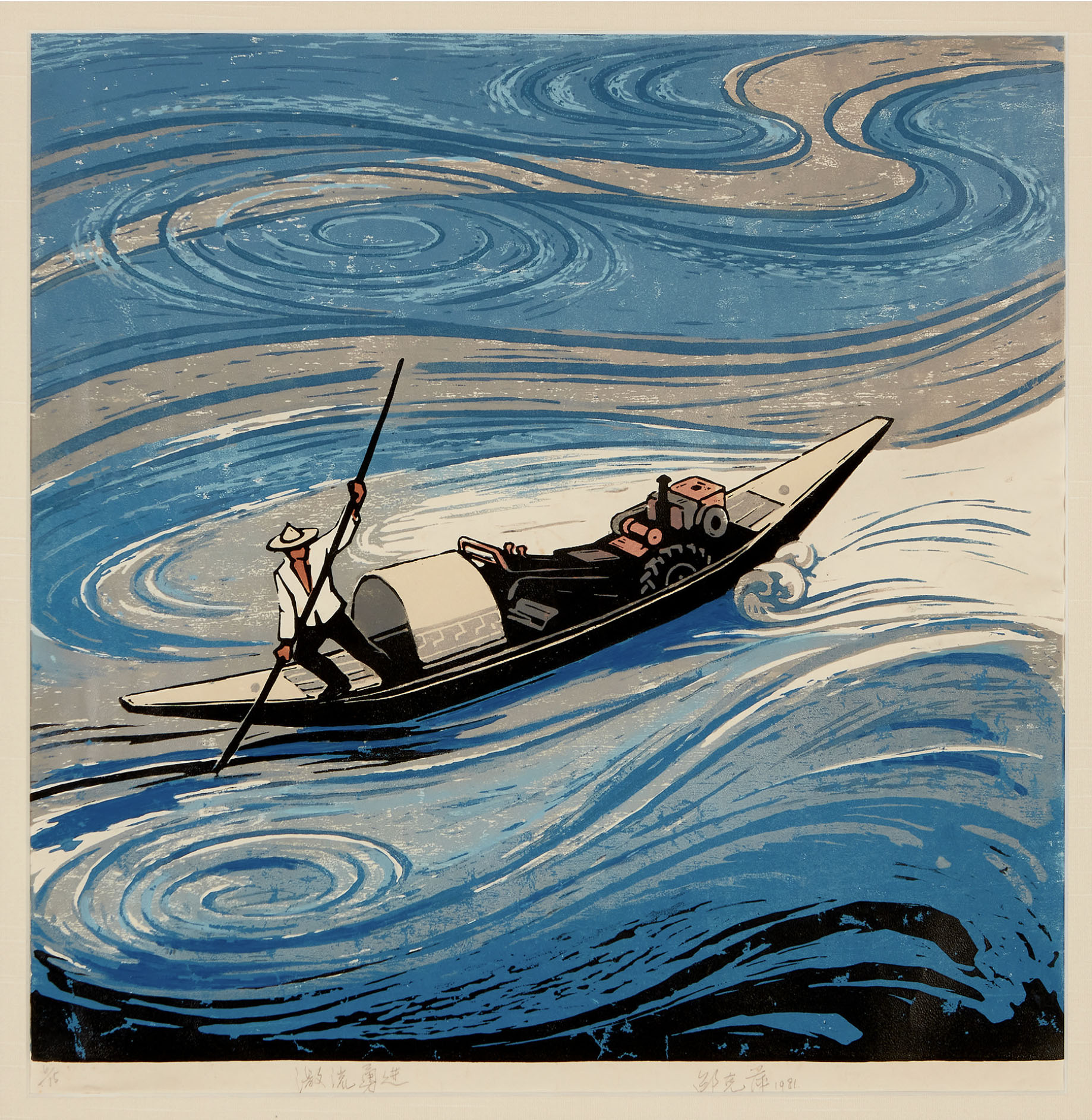

|

| Shao Keping, Floating to the Future, 1981. USC Pacific Asia Museum, gift of Charles T. Townley |

The Chinese taste for Kollwitz led to interest in her European precursors, such as Dürer. Chinese modernists adopted the Japanese use of multiple blocks for color printing.

|

| Zheng Xu, School of Fish 3, 1997 |

|

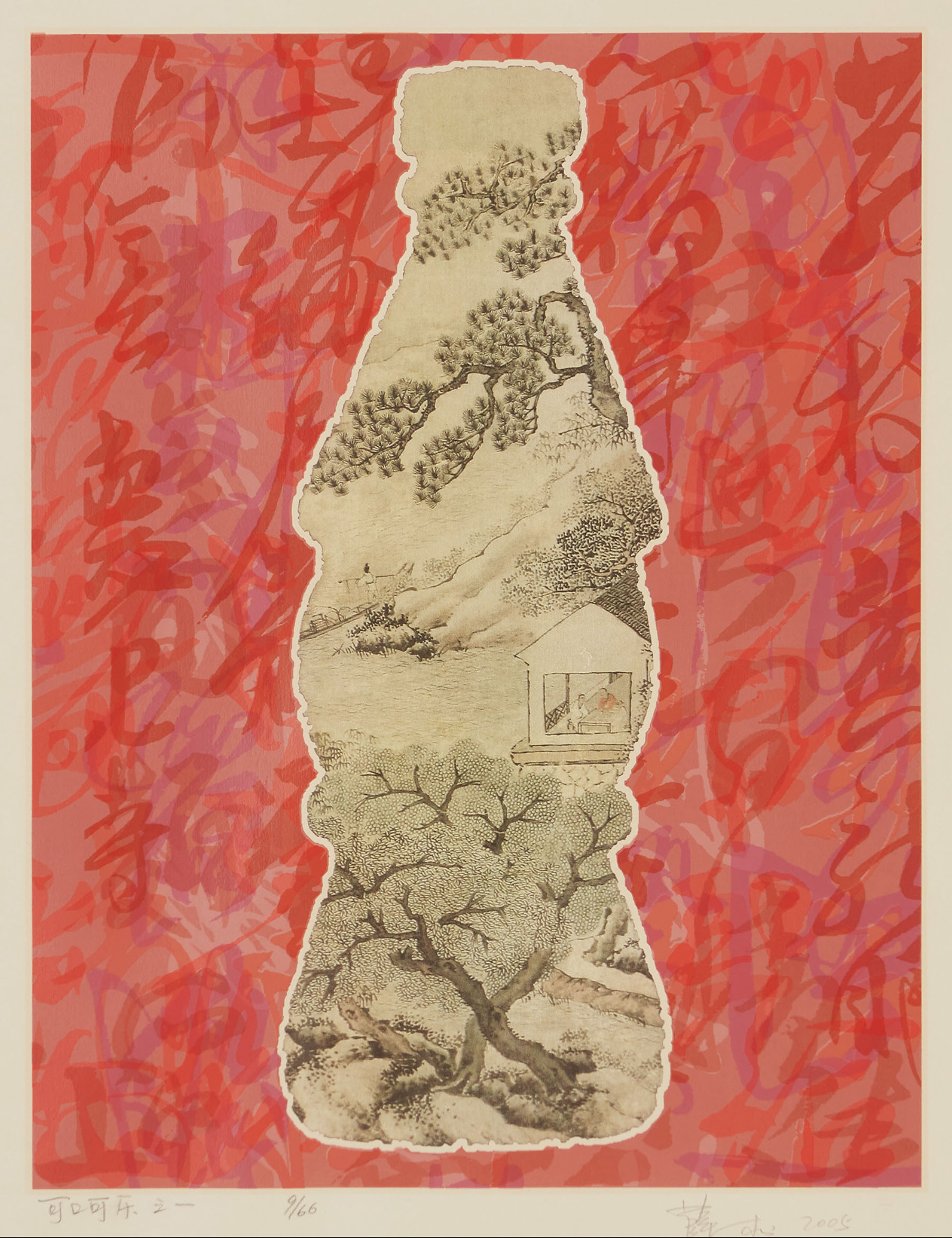

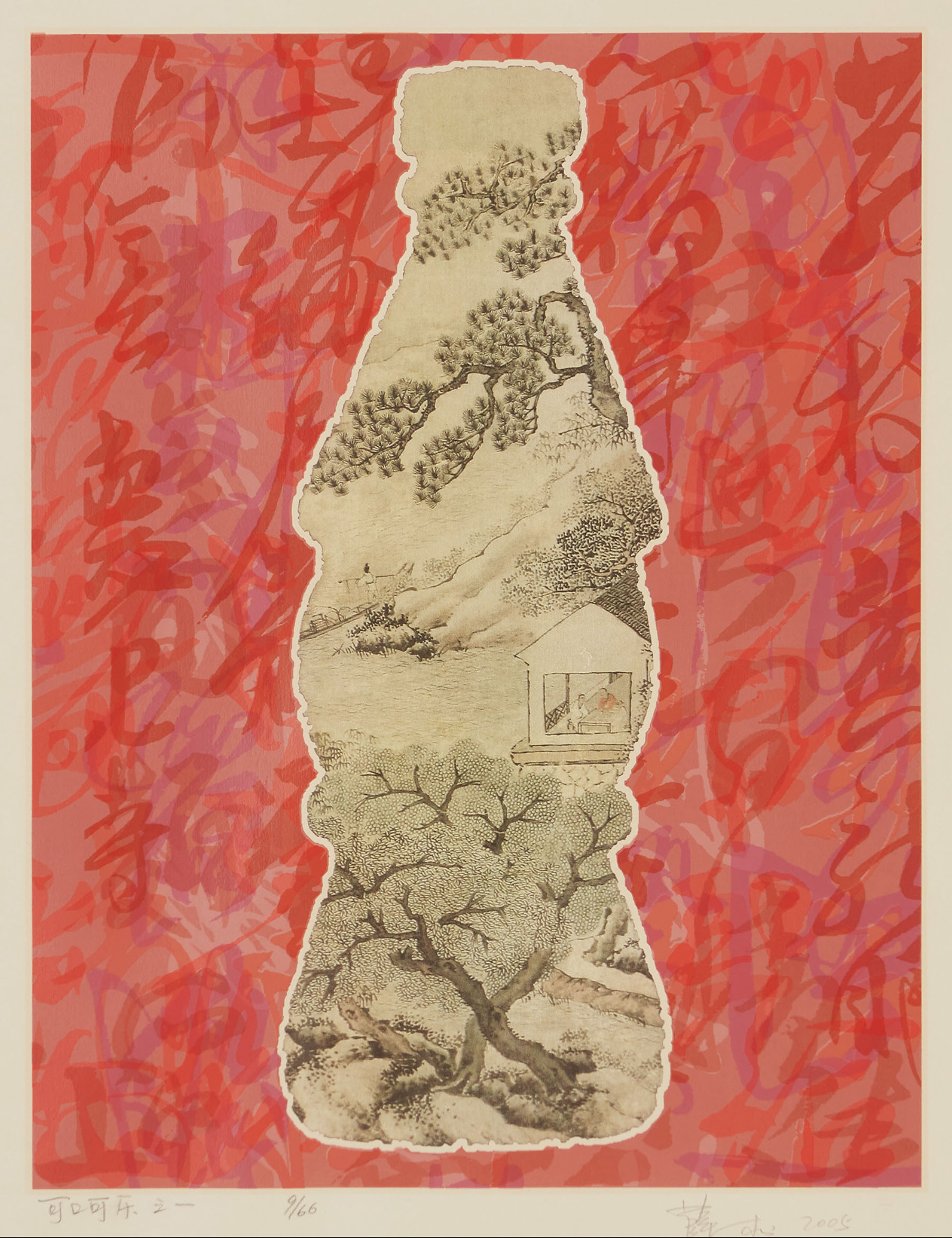

| Xue Song, Coca Cola, 2005 |

As far as anyone can tell, China has priority for the invention of both woodblock and silkscreen printing. Warhol's revival of the latter prompted post-Pop takes on global consumerism, such as Xue Song's Coca Cola.

Comments

Sun Xun's "Time Spy" of 2016 (still of 3D woodcut animation), albeit interesting, made me have to turn away...for fear of mind melt.