Camp and Rejlander

|

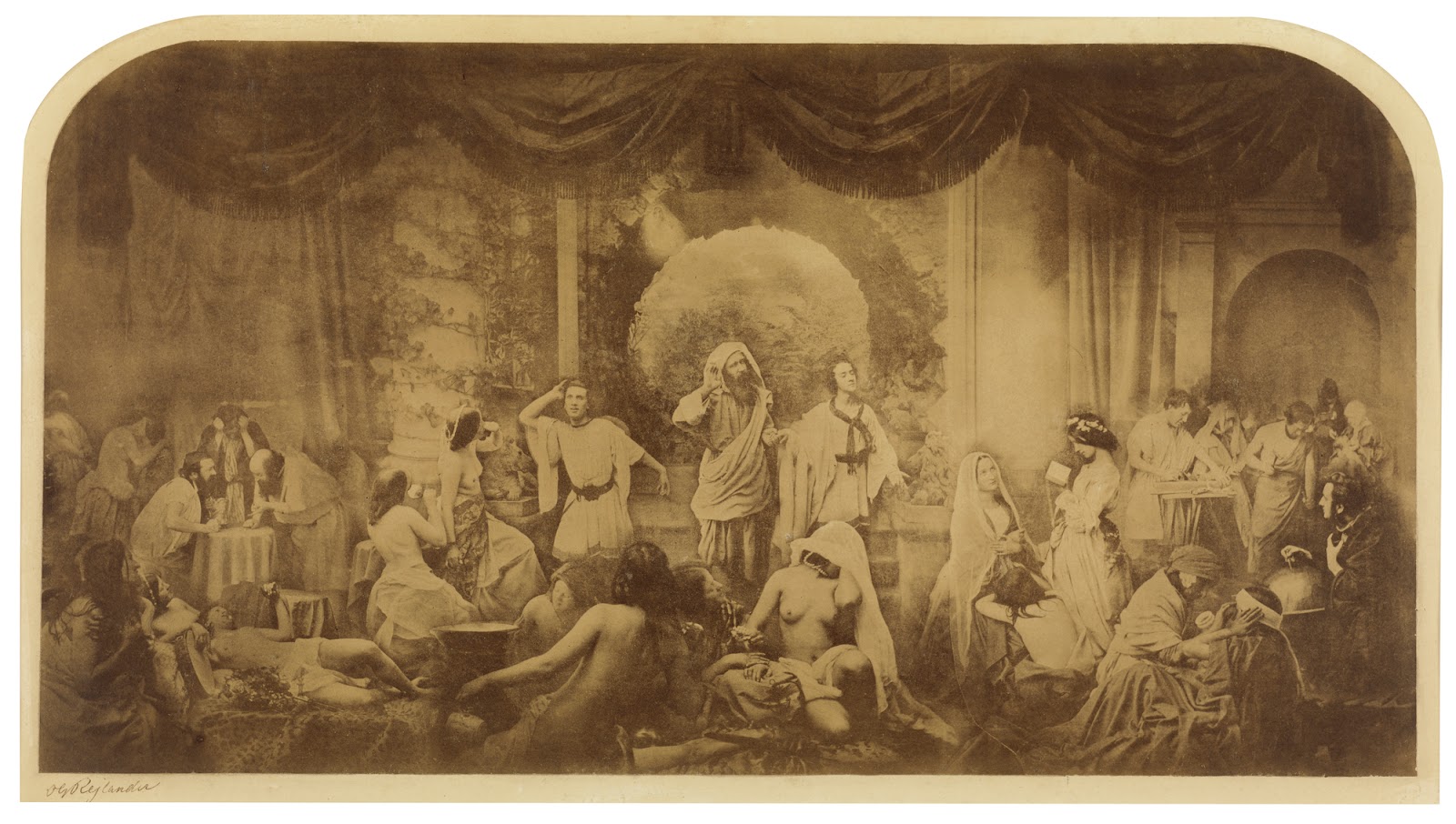

| Oscar Gustaf Rejlander, Two Ways of Life (Hope in Repentance), 1857. Moderna Museet, Stockholm |

Camp taste "relishes rather than judges," as Susan Sontag wrote. "What it does is to find the success in certain passionate failures." In "Notes on Camp" (1964) Sontag articulated a mostly urban gay aesthetic that was becoming central to the emerging Pop movement. Camp also describes the usual contemporary reaction to the picture that made Rejlander's reputation, and secured him a small though solid niche in photographic art history: Two Ways of Life (1857). It's a moralizing potboiler collaged from multiple negatives. Its original audiences had never seen anything like it, a salon "painting" with the verisimilitude of a photograph.

The fascination of the Getty's "Oscar Rejlander: Artist Photographer" is that it zooms out to survey the full production of this Swedish-born photographic pioneer. It gravitates between two ways of art, respectably serious and camp. It's no surprise which wins here. I was most taken, not by Two Ways, but by a less-heralded picture with an equally remarkable title: Mental Distress (Mother's Darling).

|

| Oscar Gustaf Rejlander, Mental Distress (Mother's Darling), 1871. The Royal Photographic Society Collection at the V&A. Image (c) Victoria & Albert Museum, London |

It's an amazing photograph even before you learn one jaw-dropping fact: It was commissioned by Charles Darwin. The naturalist was writing a book on facial expressions and asked Rejlander to supply photographs.

Rejlander took a baby photo to represent "mental distress." It was too small to reproduce well in Darwin's book. Rejlander made a drawing after the photograph, and photographed the drawing with a solar enlarger.

|

| Oscar Gustaf Rejlander, Mr. Collett's Return, 1841. Usher Gallery, Lincoln, UK |

Rejlander printed many copies of Mental Distress and sold them as independent works of art. It was identified with the child-hero of Ginx's Baby, a satirical novel by Edward Jenkins that was published the same year (1871).

The Getty is pairing the Rejlander show with "Encore: Reenactment in Contemporary Photography," a selection of works by seven artists who revisit staged (and stagey) photography. All are women or persons of color who use tableaux vivant to tweak a history of exclusion. The connection to Rejlander might seem facile. On the other hand, Rejlander's mission was to counter the "exclusion" of photography from the fine arts, and he did this mainly by staging photographs to look like Old Master paintings.

|

| Yasumasa Morimura, Daughter of Art History, Theater A, 1989. J. Paul Getty Museum |

Art, like poetry, is about the impossibility of translation. Forget the runway—there's your passionate failure.

|

| Amy Adler, Amy Adler Photographs Leonardo DiCaprio, 2001 |

Comments