|

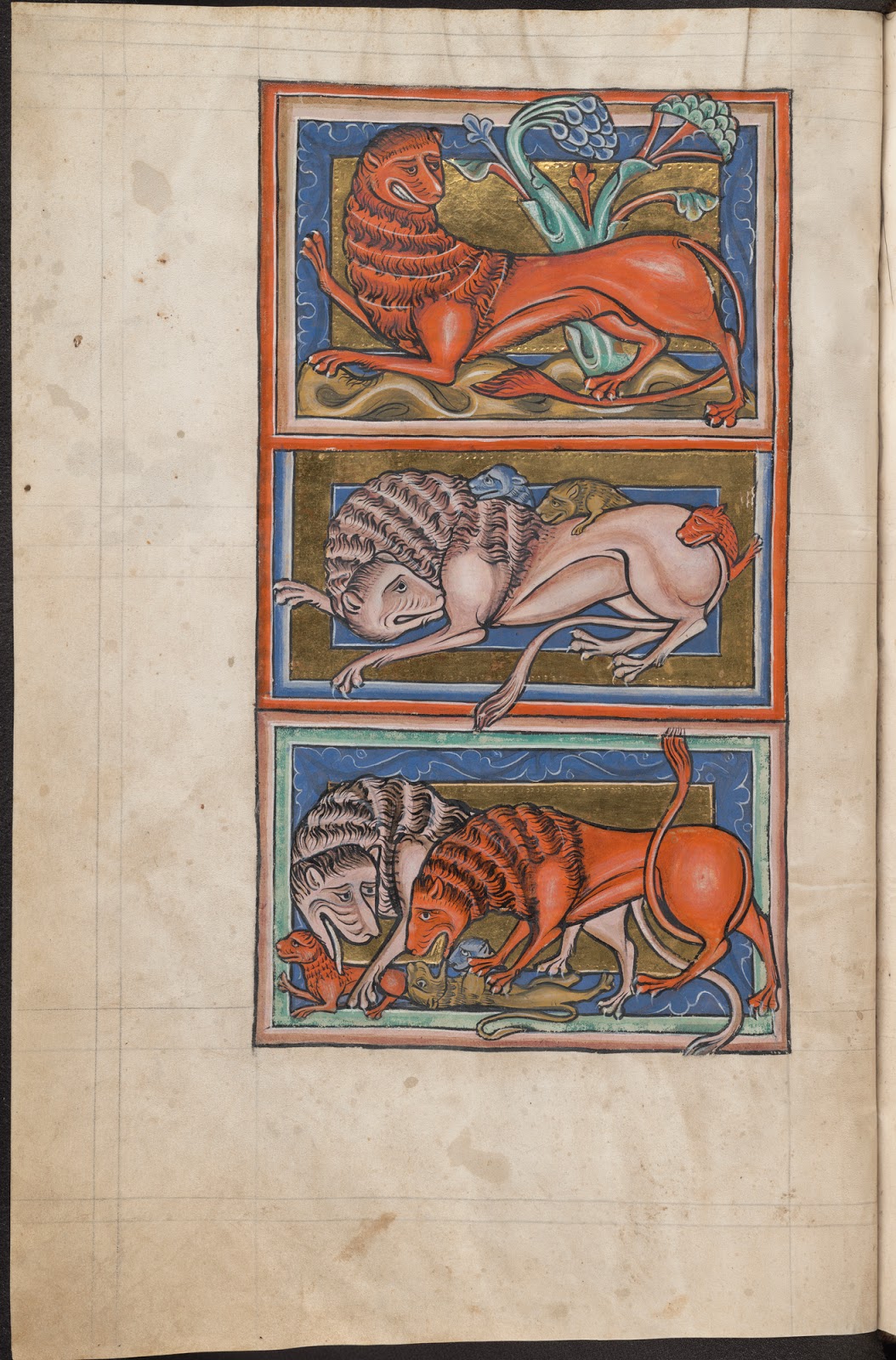

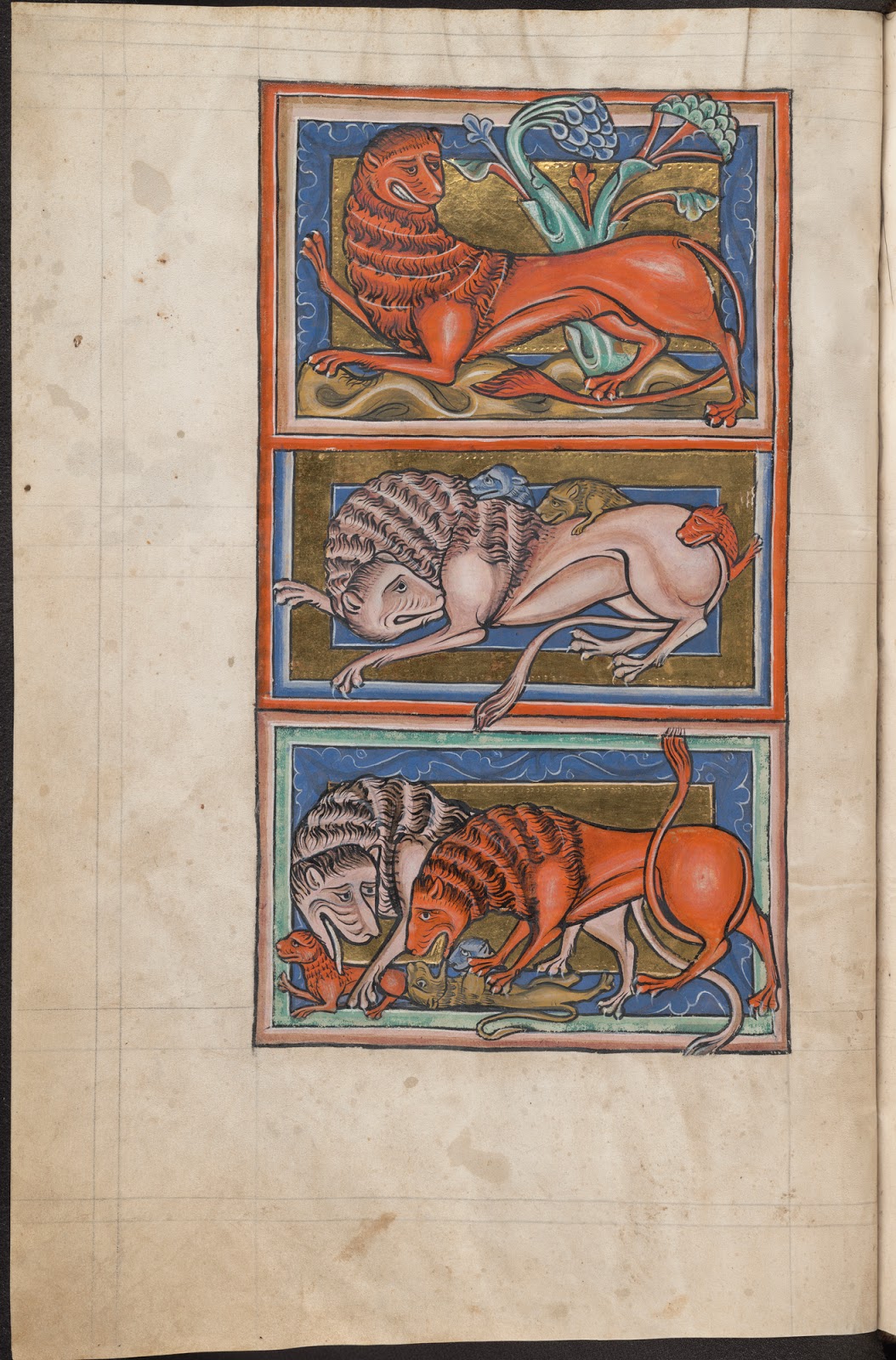

| Lions. Bestiary, about 1250. The Bodelian Libraries, Oxford |

A bestiary is a medieval picture book of animals. Written and illustrated by hand, mainly from 1180 to 1300 AD, bestiaries present lions, tigers, and hedgehogs alongside dragons, unicorns, and centaurs. Bestiaries were the cultural ancestors of natural histories, zoos, and Darwin; of My Little Pony and

Animal Planet.

Despite that cultural influence there has never been a comprehensive loan exhibition on the topic. There is now: the Getty Center's "Book of Beasts: The Bestiary in the Medieval World," curated by Elizabeth Morrison. It has brought to Los Angeles 24 of the 62 surviving illuminated bestiaries in Latin. They include the Aberdeen, Ashmole, Rochester, and Worksop bestiaries, all well-known to scholars. It's hard to imagine a comparably stellar grouping of Renaissance paintings being assembled for one exhibition.

|

| Unicorn and Lynx in the Ashmole Bestiary, about 1210-20. The Bodelian Libraries, Oxford |

|

| Adam Naming the Animals from the Northumberland Bestiary, about 1250s. J. Paul Getty Museum |

Manuscripts present challenges for exhibit designers. A single two-page opening can be shown, leaving most of a hard-won loan's illuminations unseen. This limitation is particularly felt with bestiaries, which may illustrate as many as a hundred species. The Getty show focuses on popular favorites like lions, unicorns, and dragons. "Adam Naming the Animals," a common frontispiece, serves as a visual table of contents.

|

| Ivory Casket Panel with Chivalric Scenes, France, about 1330-50 or later. Cleveland Museum of Art |

"Book of Beasts" is a almost unique as a scholarship-driven survey of medieval art that is accessible and even family-friendly. (The nearly forgotten bonnacon, the medieval fart-monster, still strikes a chord with contemporary kids and dads.) The bestiary tradition influenced animal imagery in many media, European and Islamic, devotional and secular. The show juxtaposes manuscripts, printed books, sculpture, tapestries, stained glass, ivory, painting and—in the final gallery—modern and contemporary art inspired by the bestiary meme. For good measure there's an alleged unicorn's horn and a griffin's claw.

|

| Stained glass Panel with Heraldry and the Hunt of the Unicorn. Germany or Switzerland, about 1515. Cleveland Museum of Art |

|

|

Serpent and Dragon in Bestiary, about 1255-1265. The British Library. Image: GRANGER

|

|

| Hans Hoffmann's A Hare in the Forest (about 1585) and Jan Brueghel the Elder's The Entry of the Animals into Noah's Ark, 1613 |

The Renaissance supplanted bestiaries with printed natural histories and herbals (which perpetuated much of the bestiaries' myth and folklore). German Renaissance artists zoomed in to meticulous nature studies, while Jan Brueghel the Elder zoomed out to "paradise landscapes." In these Adam naming the animals or Noah's ark provided a pious pretext for painting an encyclopedic variety of animals in a landscape. Brueghel worked from animals in the Flemish royal menagerie.

Bestaries still shape our mental landscapes, even if we don't realize it. The notions that bulls are enraged by the color red… that elephants are afraid of mice… that crocodiles cry insincere tears are straight out of the 13th century. "Book of Beasts" is a mediation on how the misinformation and fantasy of the past still shapes our so-called reality. The exhibition ends on Walton Ford's large watercolor

Grifo de California, 2017 (lent by Larry Gagosian). Ford draws on bestiaries and the 16th-century Spanish novel

Las Sergas de Esplandián by Garci Rodrígues de Montalvo. The tale describes an island guarded by fierce griffons and populated by black women who disdained men. The name of the island's queen, Califa, was appropriated for California, the only U.S. state named for a fictional black lesbian.

|

| Walton Ford, Grifo de California, 2017 |

Comments