Goya Meets Frankenstein

|

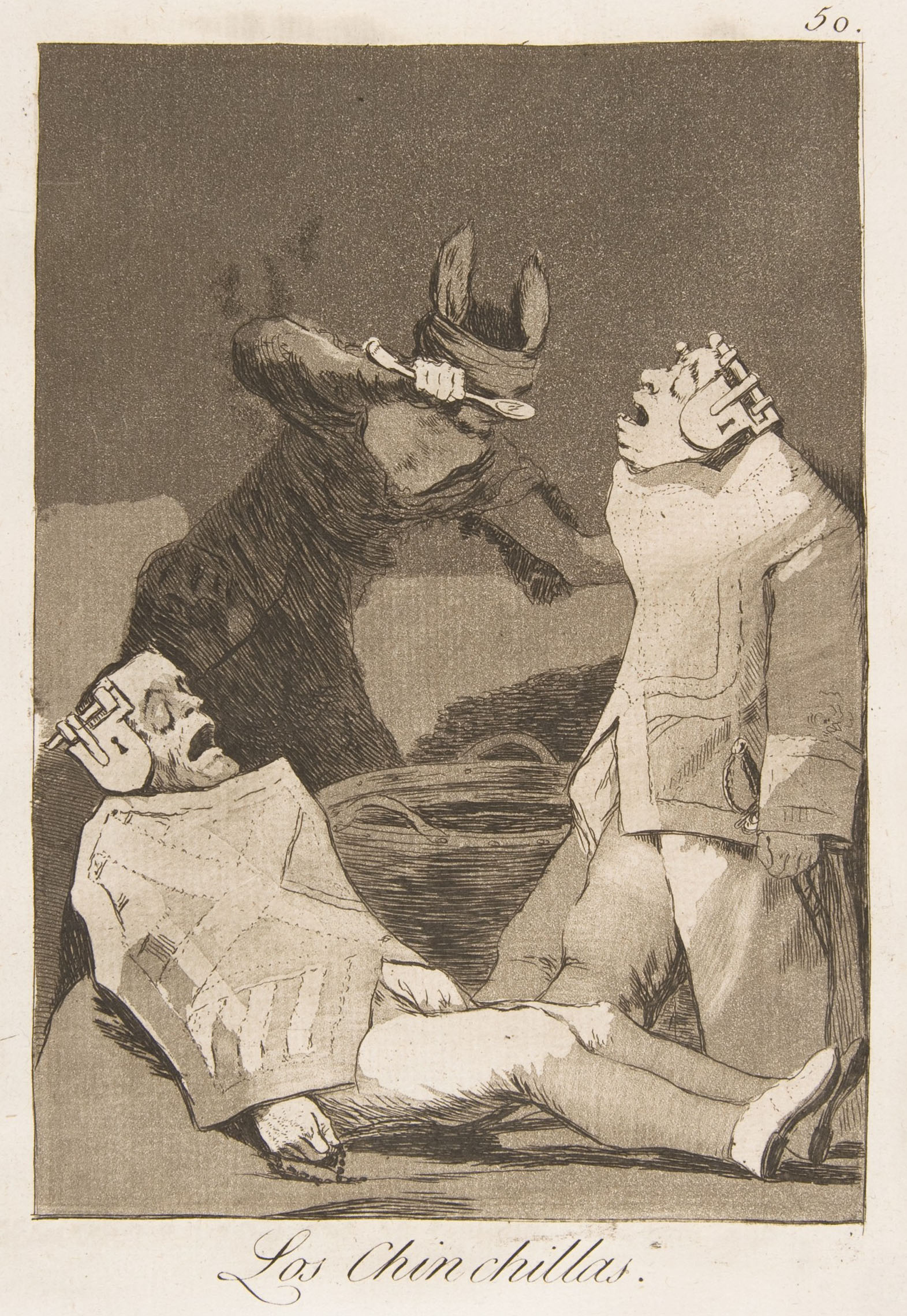

| Francisco de Goya, Los Chinchillas, 1799 |

Did a Francisco de Goya print inspire the make-up for Frankenstein's monster in the 1931 Hollywood movie? A text panel in the Norton Simon Museum's "I Saw It: Francisco de Goya, Printmaker" answers in the affirmative.

It refers to plate 50 of Goya's Los Caprichos, titled "Los Chinchillas." "The flat, square head and prominent brow ridge of the reclining figure at lower left inspired the make-up for actor Boris Karloff's role as Frankenstein in the 1931 movie." The claim is easy to believe, as the resemblance is striking. Similar claims are to be found on museum websites and online discussions of Goya's print. Yet I believe that the Goya-Frankenstein connection is an urban legend, unprovable at best. Here's why.

|

| Unknown photographer, Boris Karloff with Jack Pierce. Photo via Wikimedia Commons |

"His limbs were in proportion, and I had selected his features as beautiful. Beautiful! Great God! His yellow skin scarcely covered the work of muscles and arteries beneath; his hair was of a lustrous black, and flowing; his teeth of a pearly whiteness; but these luxuriances only formed a more horrid contrast with his watery eyes, that seemed almost of the same colour as the dun-white sockets in which they were set, his shrivelled complexion and straight black lips."

|

| Richard Brinkley Peake's "Presumption, or the Fate of Frankenstein," 1823 |

The novel was soon adapted to the stage. A publication of Richard Brinsley Peake's 1823 adaptation "Presumption, or the Fate of Frankenstein," shows a boyishly "beautiful" monster with flowing hair, akin to Jacques-Louis David's smirking 1817 Cupid. It's reported that Mary Shelley saw this production and approved the interpretation of the creature. But a sketch from the play's 1828 revival records a menacing, kouros-rigid wraith.

|

| Richard Wynn Keene, actor O. Smith as Frankenstein's monster in Richard Brinsley Peake's "Presumption, or the Fate of Frankenstein," English Opera House, Lyceum, 1828 |

|

| Karoly Grosz, poster for Frankenstein, 1931. (c) Universal Pictures |

The former reproduces Los Chinchillas. Frayling writes,

"Instead of Mary Shelley's beautiful but scary creature, her new Adam, instead of Peake's dark-haired brute in a scarf, the Monster became a more literal thing of scars and stitches and skewers—loosely based on an image of the madhouse entitled The Chincillas [sic] from Goya's series of prints Caprichos / Caprices (1799)."

That's it. Frayling does not cite any earlier source. He does not say where and how Pierce encountered the print. The 2005 book came out 74 years after the movie and 35+ years after the deaths of its creative partners.

My guess is that Frayling noticed the similarity to Goya's print and thought it worth mentioning. But he errs (IMHO) by not acknowledging that visual similarity does not imply artistic influence. Sometimes a coincidence is just a coincidence.

|

| Henry Fuseli, The Nightmare, 1781. Detroit Institute of Arts |

Frayling's 2017 book expands on this theme, connecting Frankenstein's monster (and his bride) to a slide-show of art history. Elsa Lanchester's The Bride of Frankenstein (1935) is juxtaposed with ancient Egypt's Queen Nefertiti and Henry Fuseli's The Nightmare. It's fascinating, but again, Frayling doesn't make much distinction between coincidence and influence.

|

| Karoly Grosz, poster for The Bride of Frankenstein, 1935. (c) Universal Pictures |

The New York Times review of Frayling's Frankenstein said, "According to Frayling, Karloff’s look was directly informed by 'Los Chinchillas,' a print from Francisco de Goya’s 1799 series 'Los Caprichos,' which unfortunately isn’t pictured."

With the imprimatur of the NYT, the Goya /Frankenstein claim has since been widely taken as fact. The Philadelphia Museum of Art's collection website says of its impression of Los Chinchillas: "If these figures look familiar it may be because the makeup for Boris Karloff’s character in the 1931 movie Frankenstein is purportedly based on the foolish nobles in the print."

The "purportedly" helps. But qualifiers tend to get stripped out in the retelling, as in the NSM label.

|

| Post-1931 appropriations |

Intellectual property lawyers have split many a hair over Shelley's public domain novel and Universal's copyrighted interpretation of the monster's appearance. Visual adaptations of Frankenstein can be distinguished between those operating under Universal's license (the 1964-66 sitcom The Munsters) and those relying on fair use (FrankenBerry cereal), parody (Mel Brooks' Young Frankenstein), Shelley's text (Mary Shelley's Frankenstein), and/or counterintuitively handsome monsters (Lisa Frankenstein).

A public domain source for the Universal Frankenstein in Goya could upset this applecart. But I suspect that Frayling's claim would fail to stand up in a court of law. In any case, the copyright for Universal's Frankenstein is set to expire in 2026.

Los Chinchillas aside, any would-be horror auteurs can find inspiration in the Norton Simon show. "I Saw It: Francisco de Goya, Printmaker" runs through Aug. 5, 2024.

|

| Installation view of "I Saw It: Francisco de Goya, Printmaker" |

Comments