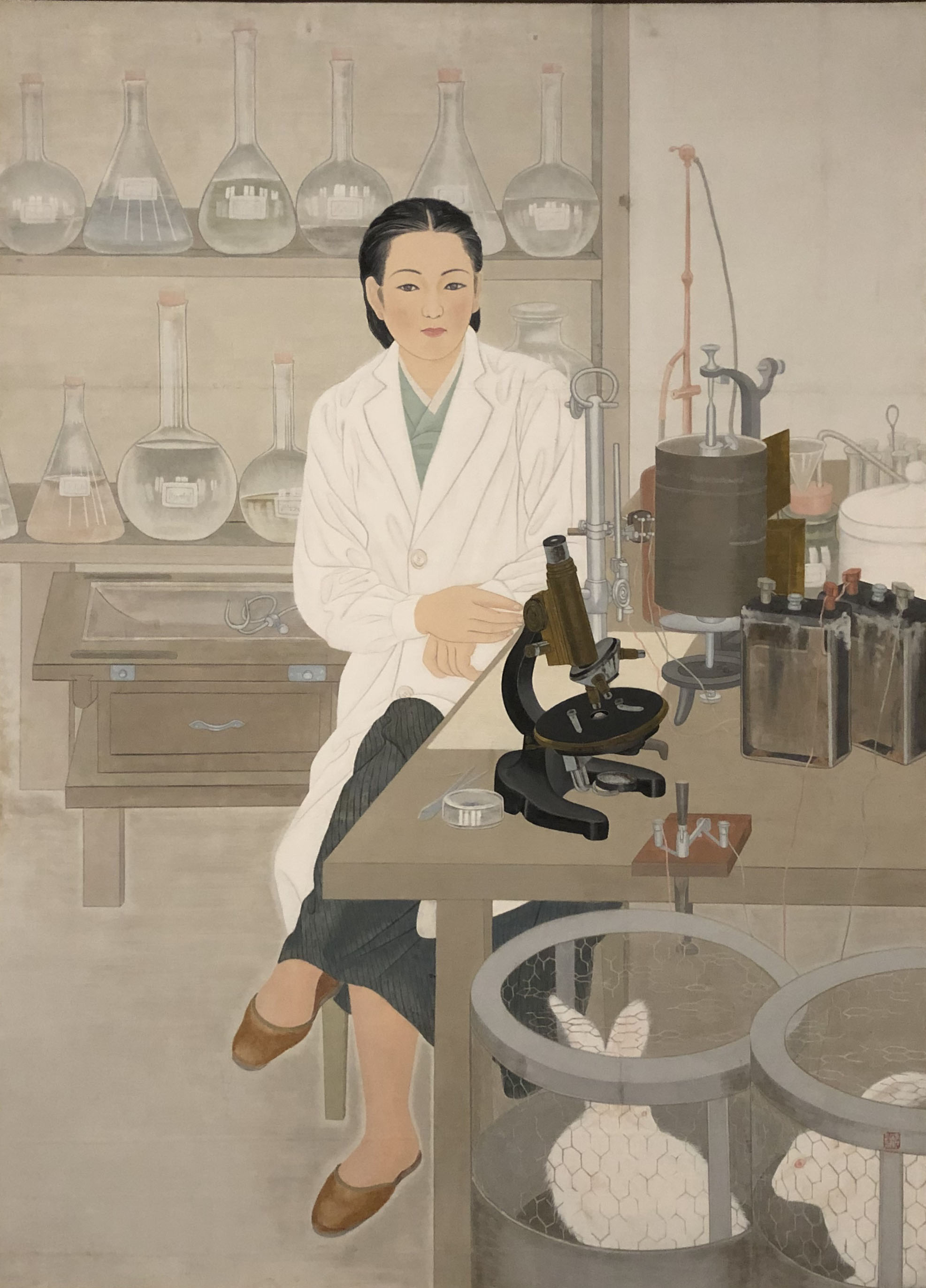

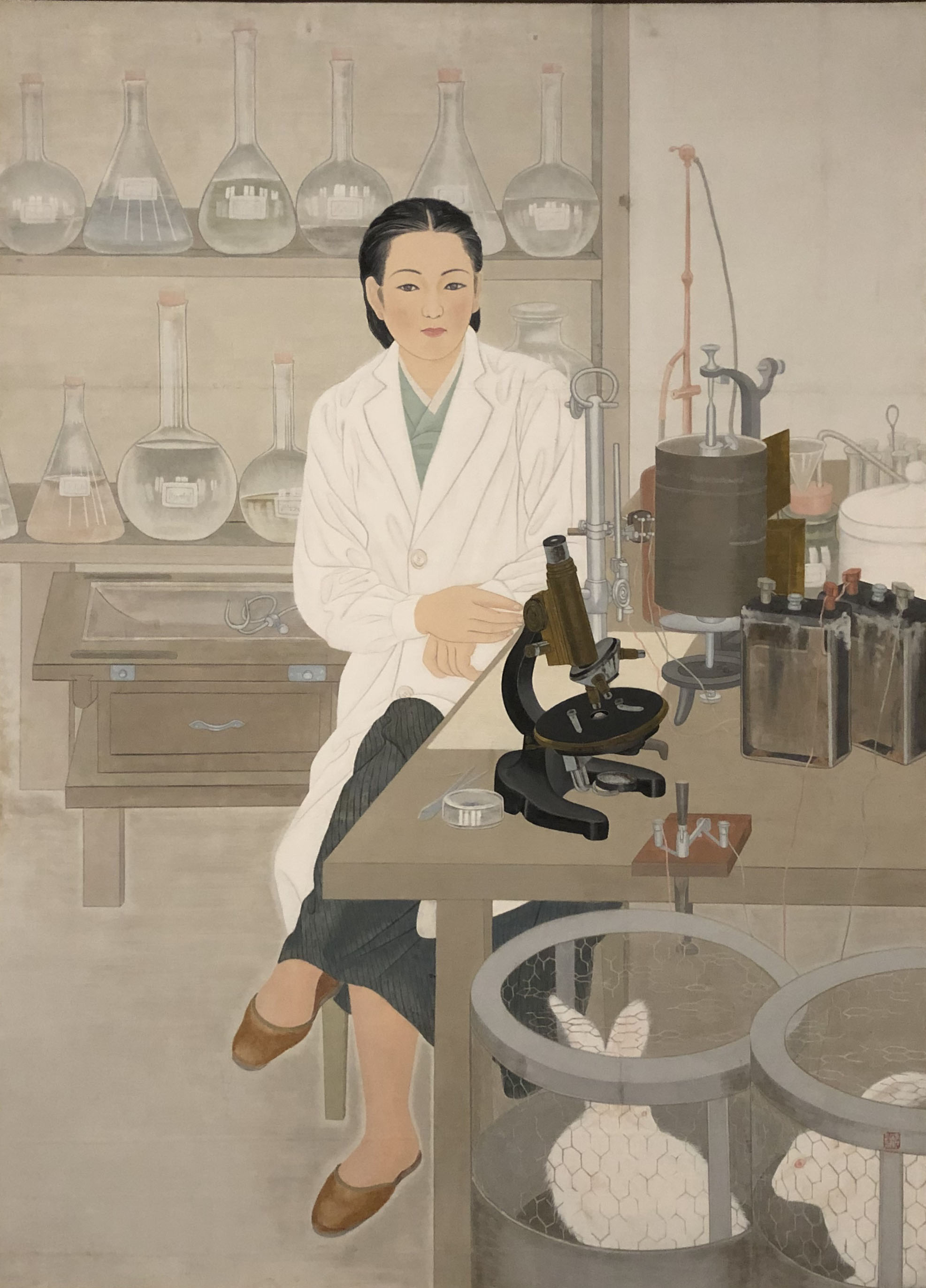

Lee Yootae,

Research, 1944. National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea

I'll bet that the median visitor to LACMA's "The Space Between: The Modern in Korean Art" has heard of 0 of the 88 artists included. Despite that, the exhibition is instantly accessible, even familiar. You will find works reflecting the influences of cubism, Socialist realism, the New Objectivity, Regionalism, the New York School, hard-edge abstraction, and process art. In some ways the story of modernism in Korea is not unlike that of the avant-garde in America. Waves of European movements inspired homegrown variants ("colonial cubism") that drew on local tradition or pointedly rejected it. Like American modernism, the Korean form is more than a retread. It doesn't take long to start appreciating the unique qualities of the roughly 130 Korean works assembled here.

As organized by LACMA curator Virginia Moon, the exhibition draws heavily on the preeminent collection of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea. It shows Korean photography alongside painting and sculpture, and it foregrounds both women artists and the independent, educated "new woman" (Sinyeoseong) as a symbol of modernity.

The exhibition begins with works illustrating the influence of photography, introduced at the end of Joseon dynasty, on painted portraiture. The Japanese colonial period (1910-1945) coincided with high modernism in Europe. In Korea the school of Paris was thus filtered through Japan and its art schools. WWII was quickly followed by the Korean War and partition. In South Korea, the postwar U.S. art scene became an important influence.

|

| Kim Whanki, Mountain and Moon, 1958. National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea |

Kim Whanki (1913-1974) is one of the show's breakout stars. He had an impressive career in the West, living in Paris in the late 1950s and having multiple New York shows in the 1960s. As seen here, he's a nimble abstractionist spanning hard-edge and painterly techniques.

Mountain and Moon rethinks classic Korean subject matter in oil paint on canvas.

| | Quac Insik, Artwork, 1962. National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea |

|

Quac Insik dug pits matching the dimensions of glass panes. He broke the glass by dropping a metal weight on it, then carefully reconstructed the pieces in a frame.

|

| Installation view. The large painting of struggling nude figures (left) is Lee Qoede's Group IV, about 1948 |

|

| Pai Unsoung, Family, 1930-1935. Private collection |

After losing his father, Pai Unsoung was taken in by a wealthy family who allowed him to become the first Korean artist to study in Europe. This depiction of his benefactors observes the traditional Korean palette, but the European dog and Western shoes (far left) were signifiers of wealth and a globalizing Korean economy. Speaking of that, the LACMA exhibition is sponsored by Hyundai, includes works collected by a chairman of Samsung, and has audioguide content by global K-pop star RM.

|

| Jung Hae Chang, Lady, 1930s, printed 1995. Gelatin silver print. Jipyong Collection, Research Institute for the Visual Language of Korea, Seoul |

|

| Lee Quoede, Self-Portait, late 1940s |

|

| Pen Varlen, Panmunjeom Hall of the Armistice Talks in 1953, 1954. National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea |

This small, striking painting is one of the few North Korean pieces in the show. Pen Varlen, of Korean ethnicity, was born in Russia and studied Socialist Realism in Leningrad. In 1953 the Soviets sent him to North Korea to reestablish the Pyongyang University of Fine Arts.

Panmungeom Hall shows the room where the Korean war's cease-fire was negotiated.

|

| Yoo Youngkuk, Composition, 1957. National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea |

|

| Seung-taek Lee, Tied Stone, 1958. The Rachofsky Collection, Dallas |

|

| Lee Hyoung Ron, Solitude, 1960. Gelatin silver print. Jipyong Collection, Research Institute for the Visual Language of Korea, Seoul |

|

| John Pai, untitled, 1963. Steel. Collection of the artist. |

|

| Kim Chong Hak, Work 603, 1963. National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea |

"The Space Between" runs through Feb. 19, 2023, in the Resnick Pavilion.

Comments

Global surrealism at the Met. The National Gallery UK, for the first time, launching an overview of Winslow Homer.

Let's see this everywhere.

Some of that's affected by geographic biases (Westerners sniffing at Easterners, Europeans sniffing at Americans, New Yorkers sniffing at Californians, etc) or cultural-political biases (the politically correct sniffing at the politically incorrect, etc).

Throw in the idiosyncrasies of personal taste (the Lucas Museum will be a major illustration of that) and it's one giant crapshoot. But to accommodate such a large world, a museum should have as much square footage as possible. Which is why tiny MOCA on Grand Ave and reduced-size LACMA on Wilshire Blvd are not exactly ideal or the best way to go.

The Insik piece could have been inspired by Duchamp's Large Glass (1923) which was accidentally and fortuitously broken upon transport to its first exhibition.

Duchamp chose not to fix the break because he thought the break added something uncanny to the piece.

Duchamp's "break" has quite a legacy. Breaking glass also figures in the work of Larry Bell, Jorge Macchi, and Alex DaCorte. DaCorte's "broken window" series and Macchi's "Parallel Lives" come closest to recapturing the spirt of Duchamp's Large Glass in so much as they repurpose Duchamp's major themes in Large Glass, sacrifice (Da Corte) and repetition (Macchi).

--- J. Garcin