|

| Christen Købke, Portrait of Professor Christian Sibbern, 1833. SMK—The National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen |

"Danish Art" would be a tough Jeopardy! category. Most Americans' knowledge begins and ends with The Little Mermaid, Edvard Eriksen's 1913 bronze sculpture in Copenhagen harbor, sharing a name with a Disney remake of a Hans Christian Anderson fairy tale. Eriksen's place in art history is slight, but an earlier school of Danish art gets a well-deserved survey in the Getty's new exhibition, "Beyond the Light: Identity and Place in 19th-Century Danish Art."

Organized with the Metropolitan Museum and the National Gallery of Denmark, it brings together drawings, sketchbooks, oil sketches, and paintings from the first half of the 19th century, Denmark's "Golden Age." The period was scarcely known to Americans prior to a 1993 exhibition at LACMA and the Met. That led to new scholarship and a spate of U.S. museum acquisitions, especially in New York. The Met and Morgan Library & Museum account for nearly a quarter of the objects in the current exhibition. The National Gallery of Denmark is the primary lender.

|

| Adam August Müller, The Hall of Antiquities at Charlottenborg Palace, Copenhagen, 1830. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

|

Denmark was the medieval stronghold of the Vikings and Prince Hamlet. Its imperial ambitions frayed in the Napoleonic Wars, losing Norway to Sweden and much of its southern territory to Germany. But like 18th-century Venice, Copenhagen became an artistic powerhouse even as its geopolitical power ebbed. It drew foreign art students, including the Germans Philip Otto Runge and Caspar David Friedrich. A key figure was Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg, who studied with David in Paris and spent a long career as teacher at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. Eckersberg mentored the next generation of Danish artists, including Christen Købke, Johan Thomas Lundby, and Martinus Rørbye. Their work, a blend of empiricism and the ideal, focuses on landscape as a medium of Danish identity. The show is no less striking for its portraits, mostly small, in pencil, and of a fellow artist.

|

Constantin Hansen, A Group of Danish Artists in Rome, 1837. SMK-The National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen. Image: SMK Photo/Jakob Sjou-Hansen

|

The landscapes aren't all Danish. Most of the artists traveled, and there was a community of of Golden Age expats in Rome, as recorded in a painting by Constantin Hansen. The artist disputed the term "Golden Age": his pockets never saw much gold, Hansen said.

The emergence of Paris as the "capital of the 19th century" relegated Copenhagen to provincial status. The exhibition's outlier is Vilhelm Hammershøi (1864-1916), born after many of the show's artists were in their graves. Hammershøi's silvery, minimalist interiors and landscapes have also seen a global surge of interest.

"Beyond the Light: Identity and Place in 19th-Century Danish Art" runs through Aug. 20, 2023.

|

| Christen Købke, Limewood Tree, about 1838. National Gallery of Denmark |

|

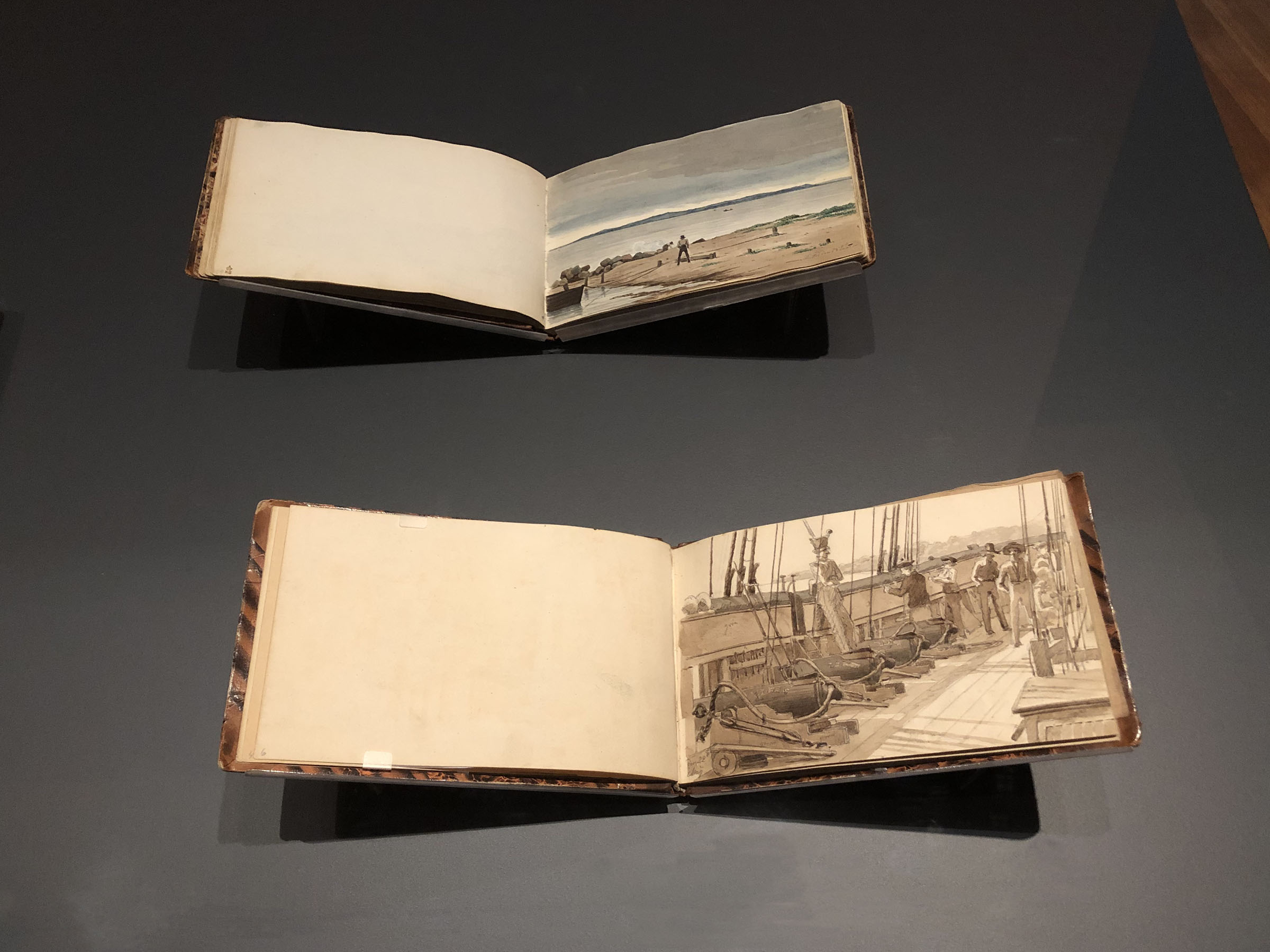

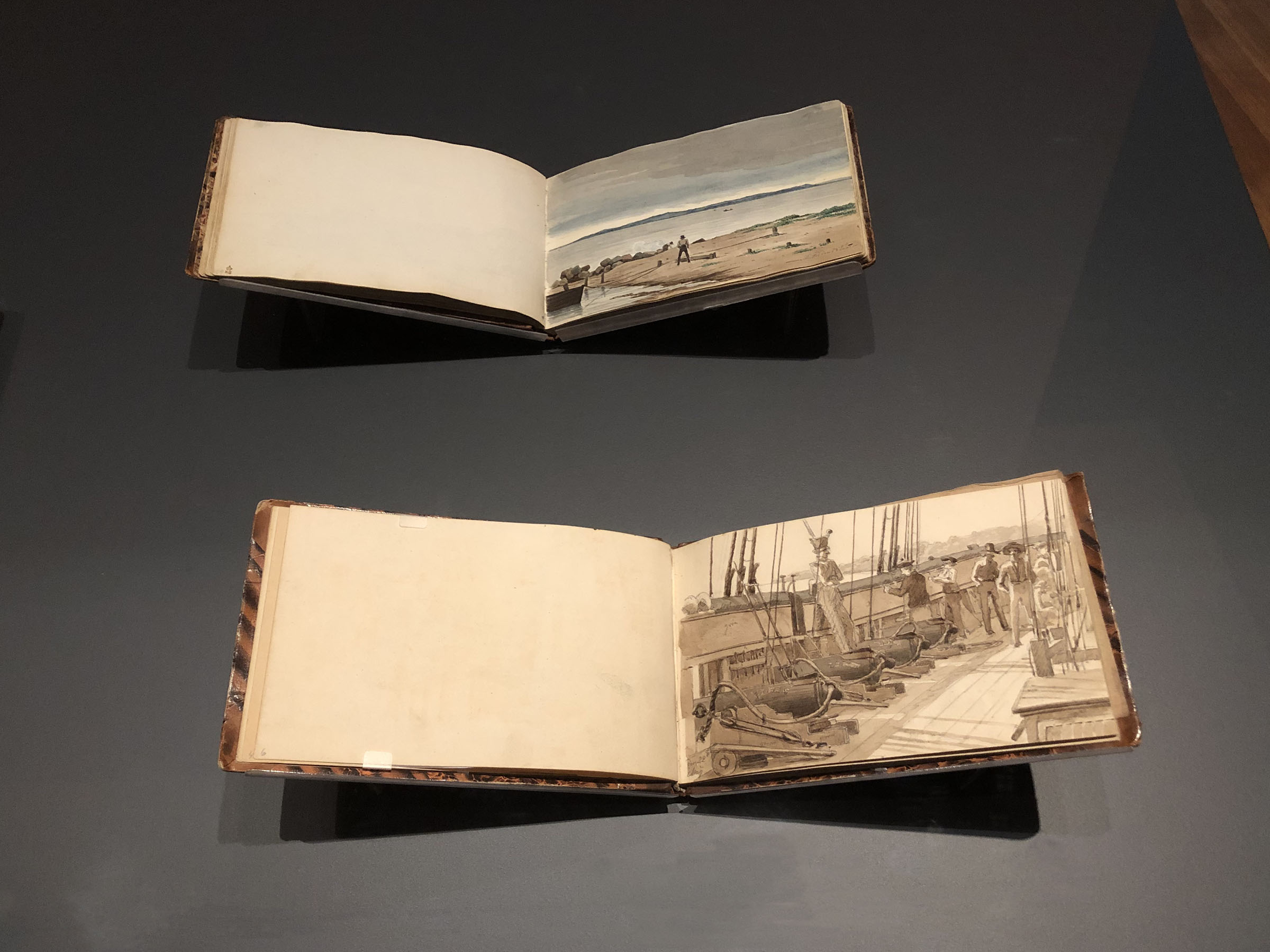

| Sketchbooks of Martinus Rørbye, early 1930s. National Gallery of Denmark |

Martinus Rørbye ventured as far afield as Constantinople (which he preferred to Rome). He recorded his travels in small sketchbooks. |

| Martinus Rørbye, Entrance to the Vicarage at Hellested, 1844. LACMA |

|

| Johan Christian Dahl, Copenhagen Harbor by Moonlight, 1846. Metropolitan Museum |

Johan Christian Dahl was born in Norway when it was part of Denmark. He spent much of his career in Copenhagen and Dresden, working in a mode closer to German Romanticism than most of his colleagues.  |

Peter Vilhelm Carl Kyhn, View from Kalvebod Strand near Copenhagen, 1853. Collection of Roberta J.M. Olson and Alexander B.V. Johnson. Image (c) Metropolitan Museum. Photo by Juan Trujillo

The Golden Age had a deep bench. There are brilliant works by lesser-known artists, and many are self-effacingly small. |

|

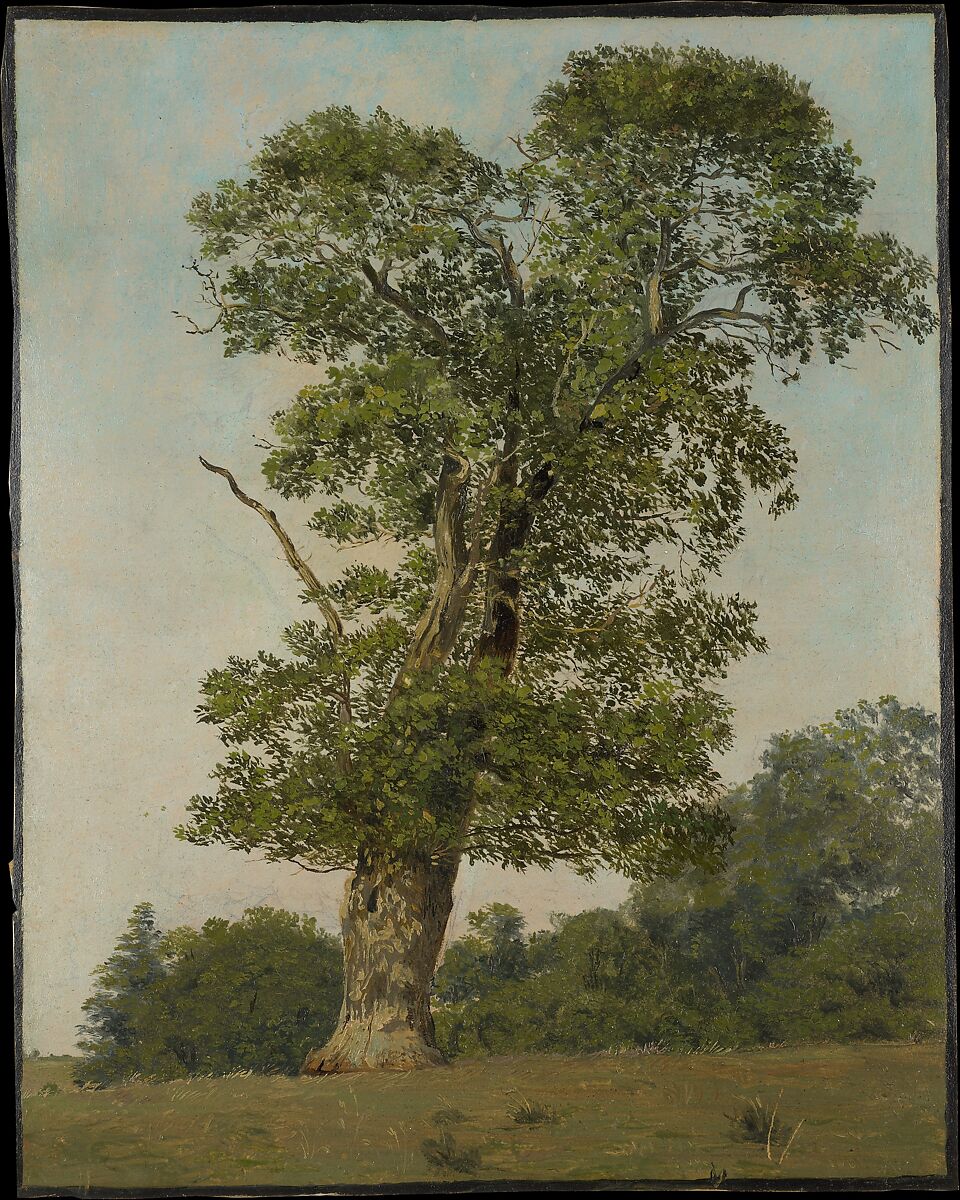

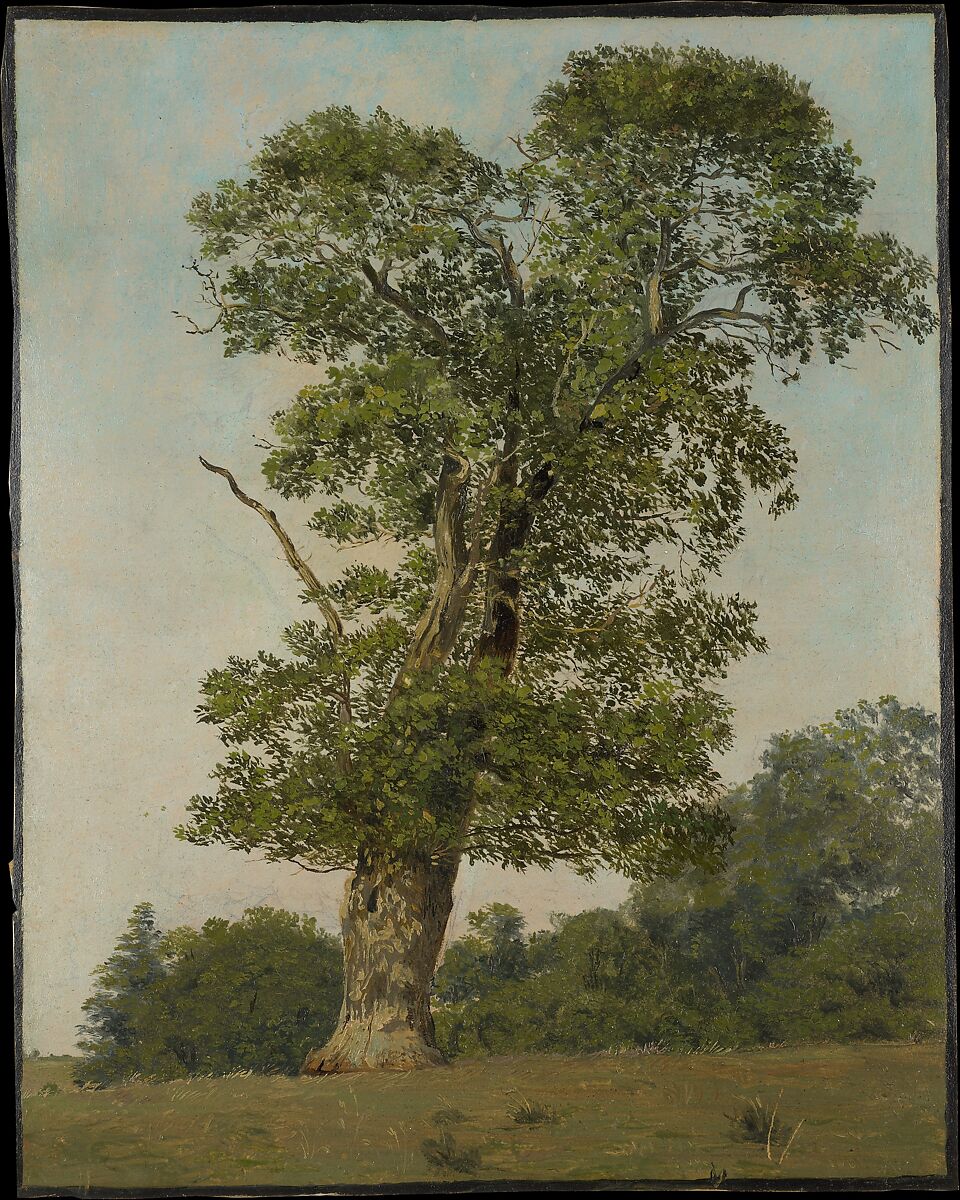

| Lorenz Frølich, A Large Oak, 1837. Eugene Thaw Collection, jointly owned by The Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Morgan Library and Museum |

|

| Wilhelm Bendz, Room in Secular Convent of Unmarried Noblewomen in Odense, 1831. National Gallery of Denmark |

Bendz's small study of light of an empty room provides a bridge to the reductive spaces of Hammershøi.

|

| Vilhelm Hammershøi, Interior with an Easel, Bredgade 25, 1912 |

Comments