|

| Patrick Jackson, Head, Hands and Feet, 2011. Hammer Museum |

Trompe l'oeil is French for

deepfake. It describes hand-crafted paintings and sculptures installed so that their illusion is taken for reality, at least momentarily. Trompe l'oeil exploits the attention economy, as do today's AI deepfakes. A pope in a white puffer jacket convinces; a pope in a meat dress presumably wouldn't.

|

| Deepfake Pope Francis, 2023, created with Midjourney |

A recent exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum unearthed Cubism's complicated frenemyship with trompe l'oeil. Considered gimmicky and middle-brow, trompe l'oeil was a perfect foil to the wise-cracking radicalism of Braque, Picasso, and Gris. Does trompe l'oeil mean anything to today's avant garde? I would have answered a hard no, but several works in the Hammer Museum's "Together in Time: Selections from the Hammer Contemporary Collection" made me reconsider.

|

| Laura Owens, untitled, 2016. Hammer Museum |

A untitled Laura Owens painting from 2016 is a proper trompe l'oeil. The painting's "raised" elements appear to hover above the canvas. Given that the average museum visitor spends ~15 seconds on a work of art, most viewers ponder the funny text and ads, not questioning whether the reliefs are real. Assuming they then walk on to the next work, they've been scammed by the oldest trick in the book: the drop shadow.

From the side, it can be seen that the raised bits are flush with the canvas. The picture is flat, save for the gobs of colored paint.

|

| Side view. (In the distance, Brandon D. Landers' 1 of 1, 2020) |

The backstory is that Owens was remodeling her Echo Park home when she discovered some old paper stereotype plates that a former owner had used for insulation. The plates were used for printing the Los Angeles Times in 1942. Intrigued by the filler stories and sexist ads, Owens used PhotoShop to collage different plates into a Frankensteinian whole. The use of mashed-up or fabricated news clippings references practices of traditional trompe l'oeil painters and the Cubists. Owens used PhotoShop drop shadows to simulate raised features and to set the page above its background (the background can also be read as a frame). The digital collage was screen-printed on a large linen canvas. Owens added juicy brushstrokes of oil and vinyl paint. The one part of the picture that's real is the paint, otherwise the raw material of illusion.

|

| Jefferson D. Chalfant, Which Is Which?, 1890. Brandywine Museum of Art. One postage stamp is real, the other painted |

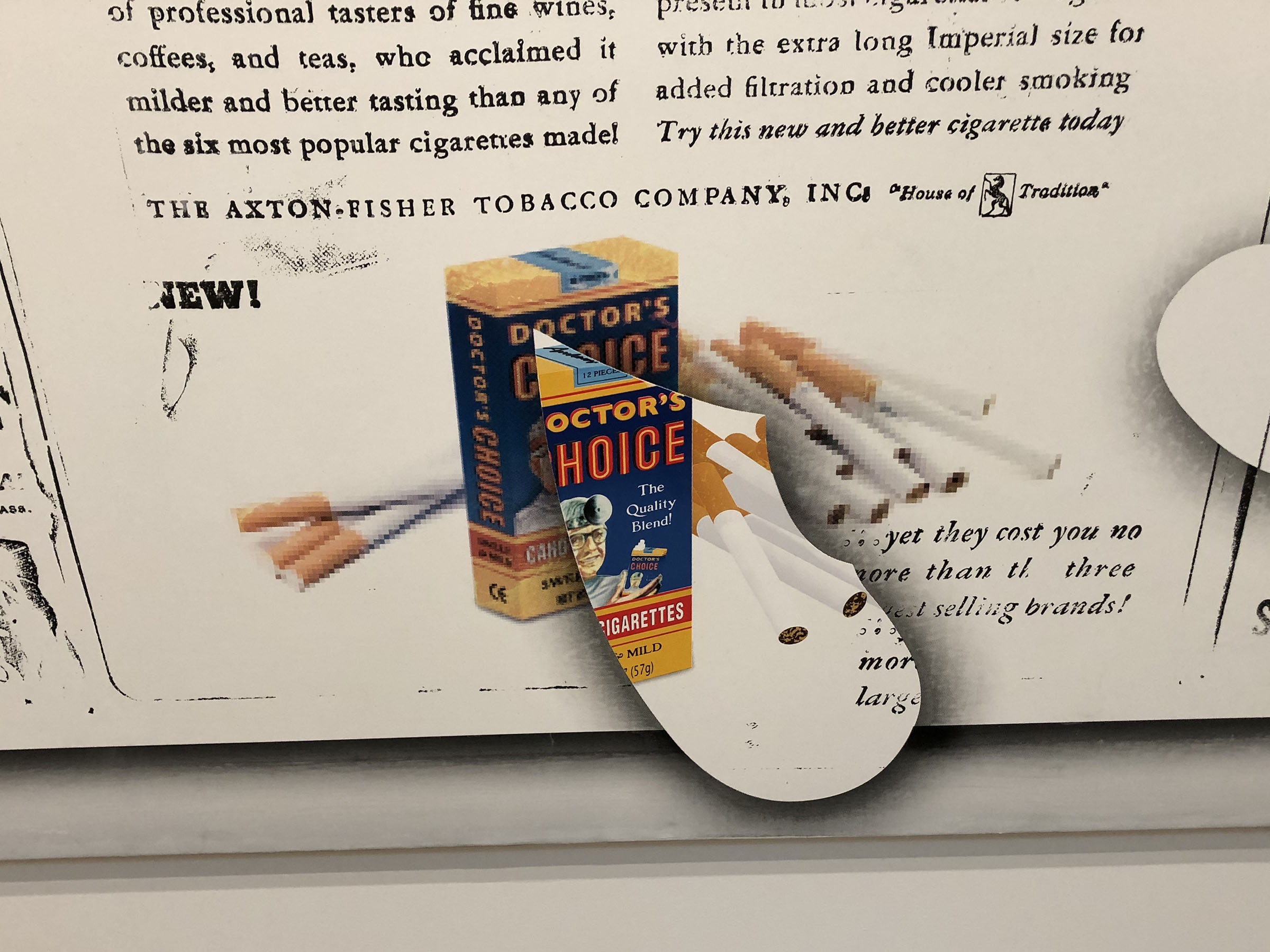

Owens thereby addresses a history of fakery, starting with the Boomer maxim "you can't believe everything you read in the newspaper." An ad for evaporated milk uses Ben Day dots, the pixel precursor now associated with Roy Lichtenstein's brand of Pop. At the bottom of the canvas, a cigarette ad is rendered in color pixels.

|

| Detail of untitled 2016 Owens with paint and Ben Day dots |

|

| Detail with pixels and faux relief element overlapping frame |

|

| Llyn Foulkes, Lucky Adam, 1985. Hammer Museum |

Once I saw Owens' painting as an exercise in/rebuttal to trompe l'oeil, I noticed other examples. Llyn Foulkes'

Lucky Adam was made three years before PhotoShop existed. The subject is Foulkes' second father-in-law, an Air Force colonel, whose blue eyes set off a mask of blood. The envelope is a real envelope collaged to the paint surface with a cord. The painting is literally a letter rack, a trompe l'oeil genre going back to the Renaissance and favored by the 19th-century school of American deepfakery.

Duane Hanson entered the trompe l'oeil pantheon when a museum guard confused one of his hyperreal figure sculptures for a real woman and called firefighters to revive her. Patrick Jackson is not playing that game, exactly, yet his two prone figures, dressed in real clothes like Hanson's, create a sense of the uncanny. The two sculptures were created for House of Double (2012), in which Jackson installed an empty apartment next to his own with simulacra of himself and his furnishings. The figures, modeled from film props, toys, and mannequins, are made of resin, silicone, human hair, yak hair, and denim clothing.

The figure at top of the post, with red hands, is easily missed, for it's installed among Armand Hammer's Old Masters, at the foot of Rembrandt's Juno. The Jackson installation reminds us that trompe l'oeil has been around a long time and, as the age of AI dawns, it's not going anywhere.

Comments