|

| Andreas Gurksy, Review, 2016. The Broad |

The Broad is showing Andreas Gursky's Review (2016) as part of its exhibition "Since Unveiling: Selected Acquisitions of a Decade." At first glance, Gursky's photograph may bring to mind an auction house or even a still from Succession. Art mavens will recognize the red abstract painting filling nearly the whole image as Barnett Newman's Vir Heroicus Sublimis (1951), now in the Museum of Modern Art. German viewers, but few uncued Americans, will recognize the four figures as German chancellors: Gerhard Schröder, Helmut Schmidt (with puff of smoke), Angela Merkel, and Helmut Kohl. This is not just a digitally adjusted image but an utter fabrication. That fact has dominated criticism of Review, and often with a note of discomfort. Gursky is better known for the hyperreal, not the fake.

When Barnett Newman first showed Vir Heroicus Sublimis, he put up a sign instructing viewers to move close to the work. Gursky's picture takes Newman at his word. A telephoto perspective flattens the chancellors against the picture plane.

|

| Barnett Newman, Vir Heroicus Sublimis (1950-51). Museum of Modern Art |

But where are the chancellors, exactly? Their chairs aren't museum seating, and this appears to be a

Rear Window view from a building across the street. There's a mullion between Merkel and Kohl. It's a visual pun, covering and replacing the dark plum stripe ("zip") in Newman's painting.

|

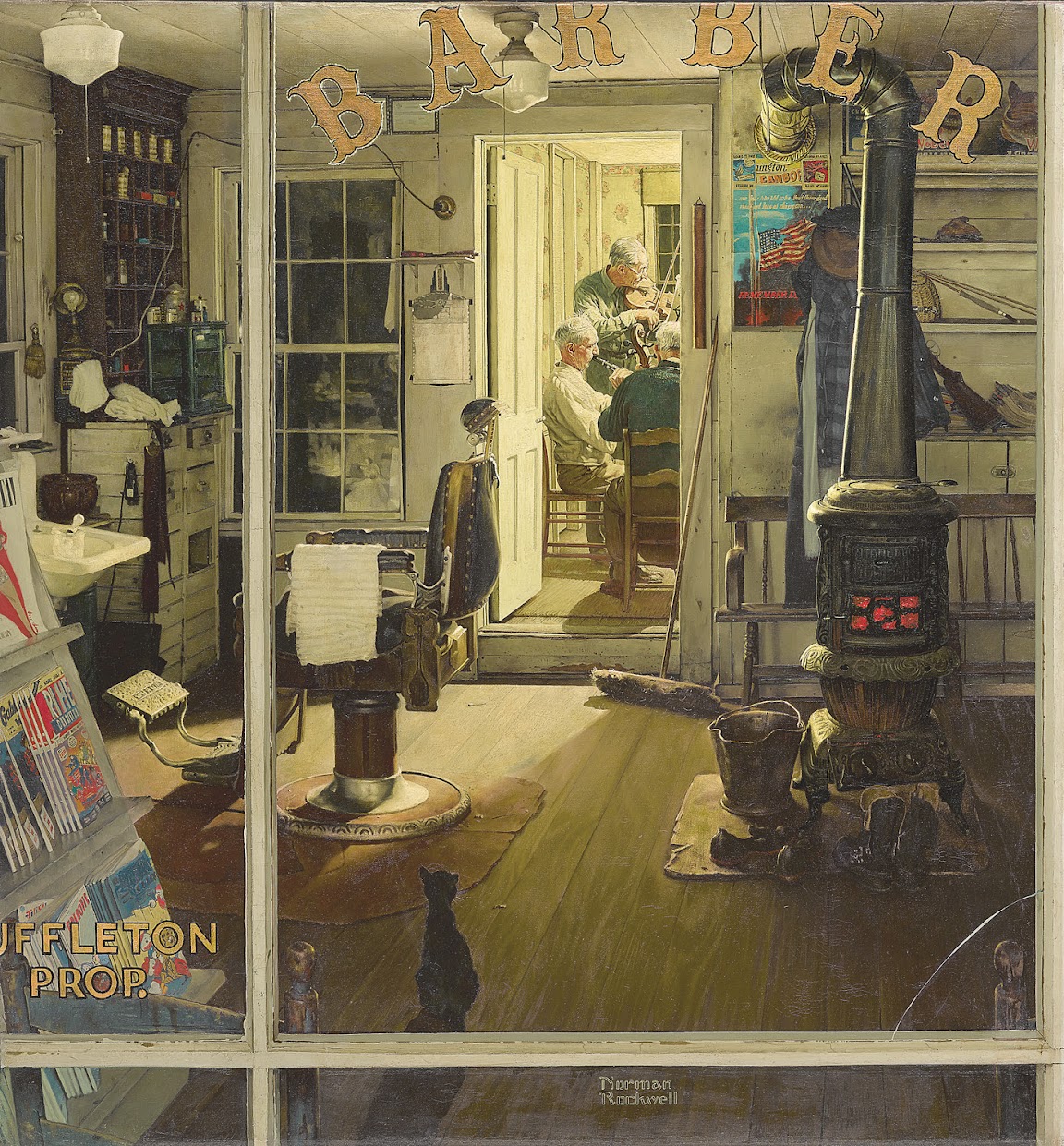

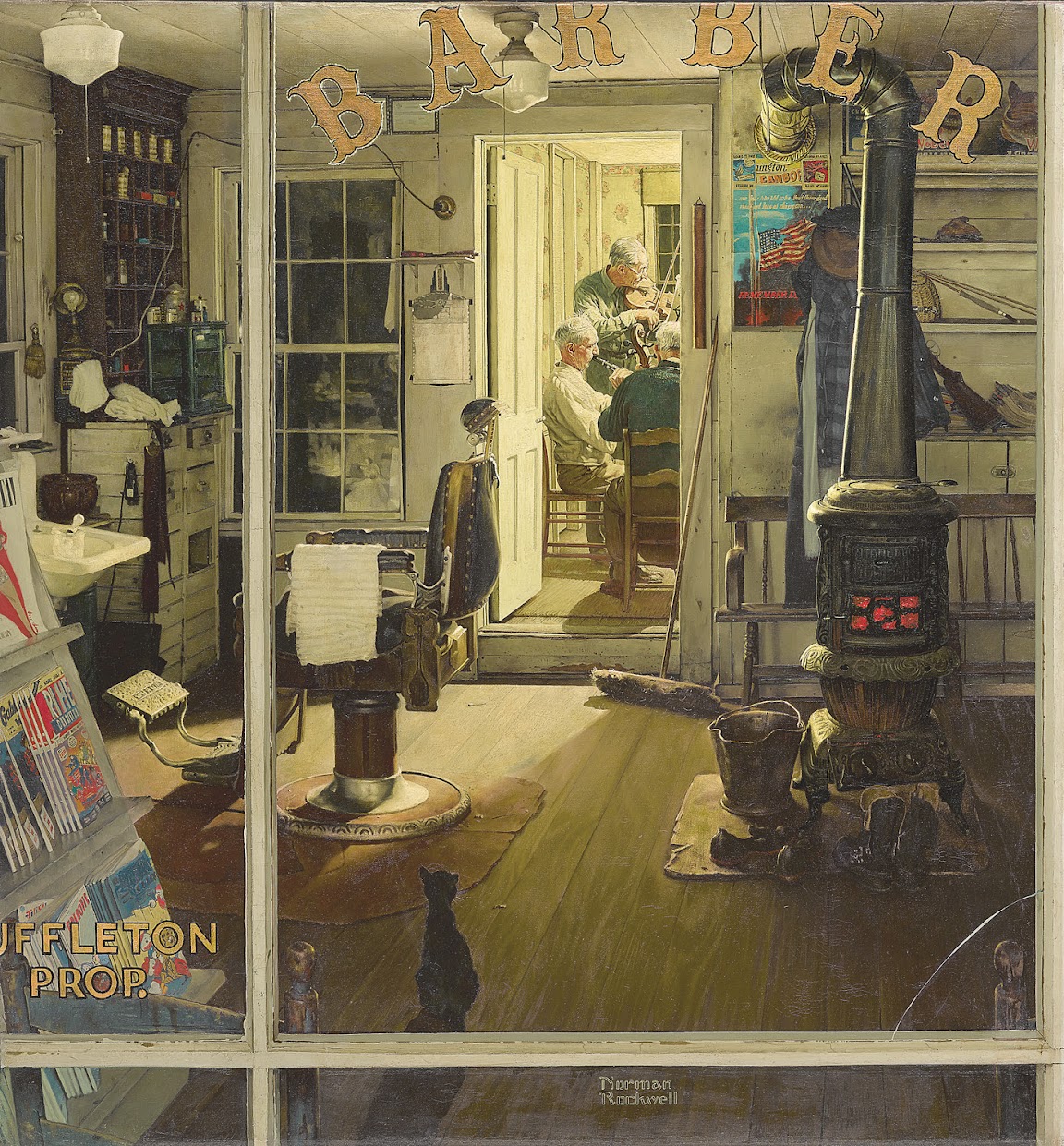

| Norman Rockwell, Shuffleton's Barbershop, 1950. Lucas Museum of Narrative Art |

Mullions figure in a very different painting created about the same time as

Vir Heroicus Sublimis. Norman Rockwell painted

Shuffleton's Barbershop for a 1950

Saturday Evening Post cover. It has been interpreted as a reaction to modernism, perhaps Mondrian with its rectilinear asymmetries.

Shuffleton's Barbershop also evinces a Cubist/Walker Evans interest in signage. Newman's painting appears text-free, though the artist signed and dated it at lower left—and supplied a portentous Latin title demanding translation ("Man, Heroic and Sublime")—and appended that literal sign instructing viewers to stand close.

Similarly, Gursky's Review has a "punch line." A figure seen from the back, looking at a landscape, is traditionally a stand-in for the viewer (Friedrich, Caillebotte, etc.) Here that initial framing unravels after a beat, once the viewer recognizes the four chancellors and then that they could not have possibly appeared together like this.

The four are one with the art, yet their hidden poker faces betray no reaction. It is left to the viewer (or writer of gallery texts) to decide what Gursky's picture means. The Broad's label describes it as "an open-ended reflection on the values of Western art and political traditions.…Review calls for viewers to consider global powers in a time of extreme precariousness, when propaganda wars hardly seem outlandish."

Perhaps Review is no less in the spirit of Ad Reinhardt's art-world cartoons. A 1946 cartoon for PM magazine makes the deadpan proposition: "An abstract painting will react to you if you react to it.… It will meet you half way but no further."

|

| Ad Reinhardt, "How to Look at a Cubist Painting," 1946 |

Comments

Perhaps the chancellors are experiencing a particularly German vista, over a Soviet horizon.

On triptychs I'm always a yes.