The Curve of Beauty

J.M.W. Turner > Frederick Evans > Aubrey Beardsley

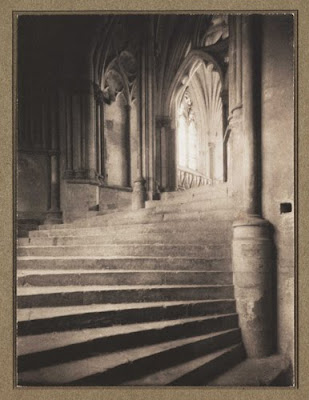

J.M.W. Turner > Frederick Evans > Aubrey BeardsleyThat's the unlikely lineage exposed in the Getty Museum's "A Record of Emotion: The Photographs of Frederick H. Evans." Evans, revered as a pictoralist photographer of cathedrals (above, Stairs to the Chapter House, Wells, 1900), said he came to that subject after seeing Turner's watercolors of church interiors, a relatively minor phase of the great Romantic painter's production.

Evans appreciated the way that Turner crammed the mysteries of light and dogma into a few square inches (left, Salisbury Cathedral, c. 1802). It's easy to see echoes of that in Evans' trademark photos of cathedral vaulting and staircases.

Evans appreciated the way that Turner crammed the mysteries of light and dogma into a few square inches (left, Salisbury Cathedral, c. 1802). It's easy to see echoes of that in Evans' trademark photos of cathedral vaulting and staircases. A more surprising link in the social network of art history is Evans to Aubrey Beardsley. It turns out that Evans "discovered" Beardsley. The future decadent was then a humble salaryman frequenting Evans' London bookstore on his lunch hour. Evans gave him his first big break, a recommendation to the de luxe publisher of Le Morte d'Arthur. Evans made a profile portrait of Beardsley and promoted him by selling platinum-print reproductions of Beardsley's drawings in his shop (both can be seen in the Getty show).

This may leave you puzzling over how Evans could be the nexus between two polar opposites of 19th-century British art. The show provides a few clues. One is an Evans photo of the spiral shell of a sectioned chambered nautilus. Another is a small album of brown-paper leaves, owned by the Getty, and opened to a postage-stamp-size pen drawing that looks like it was made with a Spirograph. Not quite. It was created by Evans with that toy's Victorian predecessor, the Harmonograph.

Invented by Joseph Goold, the Harmonograph used two pendulums to generate pleasing ink curves on paper. (Above, one of Goold's own productions.) In the Getty show, Evans comes off a shade less the seeker of spiritual light and a bit more the gadget-crazed uncle in the garage. Cameras were a gadget, after all. So were the magic lantern and the microscope, both wielded by Evans and represented here.

Invented by Joseph Goold, the Harmonograph used two pendulums to generate pleasing ink curves on paper. (Above, one of Goold's own productions.) In the Getty show, Evans comes off a shade less the seeker of spiritual light and a bit more the gadget-crazed uncle in the garage. Cameras were a gadget, after all. So were the magic lantern and the microscope, both wielded by Evans and represented here.  The perpetual sin of art history is to reduce every novelty to a banality. Notwithstanding, this exhibition makes a fairly compelling case that Evans, and perhaps some contemporaries, had a jones for a serpentine "curve of beauty" (in Hogarth's words) intersected by a series of similarly curved lines. Think of a sectioned nautilus, or the stairs of a spiral/eroded staircase, or the butterflied-shrimp form of some Beardsley drawings, such as The Black Cape from the 1894 edition of Oscar Wilde's Salome (above).

The perpetual sin of art history is to reduce every novelty to a banality. Notwithstanding, this exhibition makes a fairly compelling case that Evans, and perhaps some contemporaries, had a jones for a serpentine "curve of beauty" (in Hogarth's words) intersected by a series of similarly curved lines. Think of a sectioned nautilus, or the stairs of a spiral/eroded staircase, or the butterflied-shrimp form of some Beardsley drawings, such as The Black Cape from the 1894 edition of Oscar Wilde's Salome (above).

Comments