"Frank's Archive Is a Real Beast": Getty Gets Gehry

|

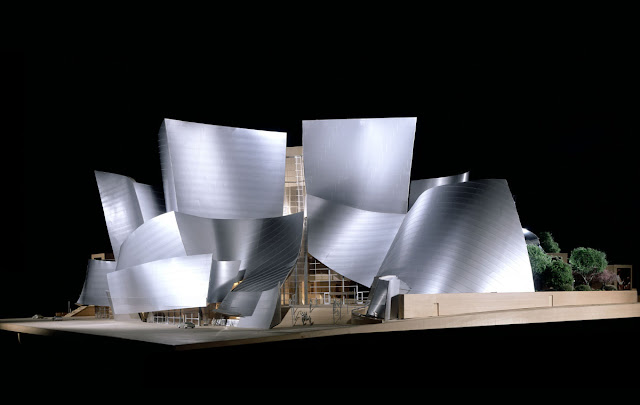

| Frank Gehry, Walt Disney Concert Hall model, 2003. Frank Gehry Papers at the Getty Research Institute, (c) Frank O. Gehry |

"I don't want to give it away—it's an asset," Gehry told The New York Times in 2007. "I've been spending a lot of rent to preserve it."

|

| Frank Gehry, Greber Studio, 1967. Frank Gehry Papers at the Getty Research Institute, (c) Frank O. Gehry |

Given Bilbao, former Guggenheim Museum chairman (and Gehry client) Peter Lewis commissioned a study on the economics of Gehry's archive. "Frank's archive is a real beast," reported Jennifer Frutchy—a "gold mine" though a potential money pit.

The Canadian Centre for Architecture is a well-funded institution with a laser-sharp focus. It made Gehry an offer he couldn't refuse: $1.5 million just for material relating to a house that was never built.

Nope, said Gehry. He didn't want to break up the archive.

Insurance tycoon Peter Lewis had offered Gehry $5 million to design a home in the Ohio suburbs. Gehry came in a bit over budget ($80 million). In so doing, he explored ideas that would later be realized in Bilbao and Disney Hall. That's why the Canadian Centre was so interested. Lewis' unbuilt home has already rated a Jeremy Irons-narrated documentary.

In 2014 Michael Govan brainstormed a Gehry tower on the south side of Wilshire, maybe incorporating a reinvigorated LACMA architecture and design wing: "There's a Gehry archive floating out there; we all know that."

The same L.A. Times piece had Gehry admitting he wanted to "get that monkey off my back." Meaning that darned archive—"it's costing me a lot to store it."

It looks like the Getty wealth was decisive. The GRI has has been scooping up archives of prime L.A. modernists—Pierre Koenig, John Lautner, Frank Israel—and also global figures such as Zaha Hadid, Philip Johnson, Peter Eisenman, Aldo Rossi, and Daniel Libeskind. It once seemed impossible for a West Coast institution to compete with MoMA in architecture. With the Gehry archive, the GRI takes a big step forward.

It also raises the question of what architects' (and artists') archives mean in the digital age. An online archive is a common good, but the owner bears the cost of acquisition, conservation, and digitization.

The Getty's first Gehry archive show opens next month. "Berlin/Los Angeles: Space for Music" will run at the GRI April 25 through July 30, 2017. It will present designs for Disney Hall against those for Hans Scharoun's 1963 Berlin Philharmonic.

|

| Frank Gehry, Norton House model, 1982-1984. Frank Gehry Papers at the Getty Research Institute, (c) Frank O. Gehry |

Comments