The Woman Who Said No to Matisse

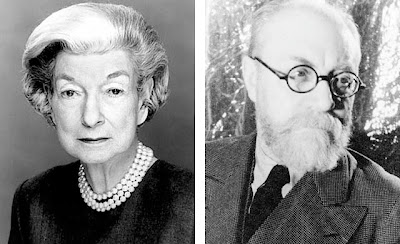

It appears that LACMA is in line for a major Matisse acquisition, The Sheaf (1953). It's a tile mural in the Holmby Hills home of storied L.A. arts patron Frances Lasker Brody (above, left), who died Nov. 12. The L.A. Times obituary confirms that the family intends to donate The Sheaf to to the museum.

It appears that LACMA is in line for a major Matisse acquisition, The Sheaf (1953). It's a tile mural in the Holmby Hills home of storied L.A. arts patron Frances Lasker Brody (above, left), who died Nov. 12. The L.A. Times obituary confirms that the family intends to donate The Sheaf to to the museum. Frances Brody was the prime mover behind the 1966 Henri Matisse retrospective held at UCLA's modest Wight Art Gallery. A decade earlier, she and her husband asked Matisse to design a ceramic mural for an enclosed patio of their A. Quincy Jones-designed home. The prospect cheered the ailing, 83-year-old Matisse. In January 1953, with nothing in writing, he set to work. He used his technique of cut-out gouache-colored paper to design the mural (he felt unable to handle a paintbrush). The result was his famous Large Composition with Masks, now at the National Gallery, Washington (below).

With no feedback from Brodys, Matisse felt so fired up that he did another cut-out design, Flowers and Fruits (below). This is now in the Musée Matisse, Nice.

With no feedback from Brodys, Matisse felt so fired up that he did another cut-out design, Flowers and Fruits (below). This is now in the Musée Matisse, Nice. Matisse was on a roll. He did still a third spec design, Apollo (below, now at Stockholm's Moderna Museet).

Matisse was on a roll. He did still a third spec design, Apollo (below, now at Stockholm's Moderna Museet). Then in May 1953, the Brodys paid a studio visit. It didn't go so well. In the Times, Elaine Woo writes,

Then in May 1953, the Brodys paid a studio visit. It didn't go so well. In the Times, Elaine Woo writes,They did not like the maquette, or paper cut-out, of the artwork he proposed for them. As the story goes, the Brodys asked the master of modern art if he could try again. Frances Brody later said that their request wasn't as audacious as that, but those who knew her said it would not have been out of character for the art maven, who often seemed imperious to those around her.

Matisse went back to the drawing board, and the result was The Sheaf. This time the Brodys approved. The ceramic artist Partigas created the tiles from Matisse's design. The Brodys donated the cut-out of The Sheaf to UCLA. Matisse also produced a lithograph of the design (pictured above).

Matisse went back to the drawing board, and the result was The Sheaf. This time the Brodys approved. The ceramic artist Partigas created the tiles from Matisse's design. The Brodys donated the cut-out of The Sheaf to UCLA. Matisse also produced a lithograph of the design (pictured above).What did the Brodys not like about the first three designs? Apparently the symmetry; perhaps the too-pretty faces. From today's perspective, it's easy to agree. All three stabs at the L.A. commission — prior to any Brody facetime — are framed by classical pilasters. Possibly Matisse took a cue from the tile medium and its architecture setting. Frances apparently wanted something more free-form and organic. "Sheaf" (a translation of the Frenchman's "Gerbe") is semi-archaic word in English. It survives mainly in the expression "a sheaf of papers." The original sense means a bundle of grain tied together. It's believed that Matisse was alluding to another Henri, Bergson. In his 1907 Evolution Créatrice, Bergson wrote,

For life is tendency, and the essence of the tendency is to develop in the form of a sheaf [gerbe], creating, by its very growth, divergent directions among which the impetus is divided.

Assuming the gift happens, how important will The Sheaf be to LACMA's collection? It would be a strong counterpoint to the artist's much earlier painting Tea (1919) and the five sculptures of Jeannette (1910-1913). It is difficult for museums to represent Matisse's final years, as the cut-outs are light sensitive (UCLA last showed its cut-out of The Sheaf in 2001). The mural could be displayed in the permanent galleries. It's big — 12 by 11 feet. LACMA doesn't have anything that size by a classic modernist.

Some might have reservations over the fact that Matisse designed but didn't fabricate the mural. This is nothing new, and the esteem of such works varies by artist. All Jeff Koons' pieces are fabricated, and so were Baldessari's text paintings. But who thinks Picasso's tapestries are anything more than oddities? The Sheaf bears comparison to Matisse's ceramic murals and stained glass for the Chapelle du Rosaire de Vence, created a couple of years before the Brody commission. Those are generally well regarded, and with the forgivable vanity of old age, Matisse called the chapel his masterpiece.

Undeniable is the importance of the hard-to-please Brodys in Matisse's late career. The reject pile for their patio commission includes some of the artist's best-known cut-outs.

Comments

Not so sure Pablo would have done that! He would have probably cursed at her and sent her on her way. Had it been a man, he would of punched him in the stomach.

I'm not saying that Matisse wasn't a great artist, just that he did so many comps to please her that he missed what she was really looking for, something from his own mind, not something he thought she would like.

In the end, art history gets another masterpiece,... and a good story as well.