Bert Cooper’s Freaky Octopus Picture

Mad Men is one of the few TV series in which the creators know something about art (unlike, say, Work of Art). Not only are the Sterling Cooper offices a wet dream of mid-century modern design, but one of the characters is an art collector. That's founding partner Bert Cooper, played by Robert Morse. He's an Ayn Rand-reading Japanophile who covets Rothko as well as traditional Asian art. Cooper's most recherché prize, revealed on the third season's opening episode, is a print of a woman being ravished by two octopuses. Gloating over the acquisition, Cooper asks, "Who is the man who imagined her ecstasy?"

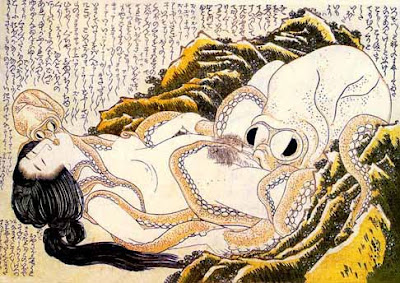

Mad Men is one of the few TV series in which the creators know something about art (unlike, say, Work of Art). Not only are the Sterling Cooper offices a wet dream of mid-century modern design, but one of the characters is an art collector. That's founding partner Bert Cooper, played by Robert Morse. He's an Ayn Rand-reading Japanophile who covets Rothko as well as traditional Asian art. Cooper's most recherché prize, revealed on the third season's opening episode, is a print of a woman being ravished by two octopuses. Gloating over the acquisition, Cooper asks, "Who is the man who imagined her ecstasy?"  Art historians are still asking that question. There's no mystery about the creator of Cooper's print: It's Katsushika Hokusai, otherwise known for The Great Wave. The octopus print, from 1814, is usually known in the English-speaking world as The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife. But Hokusai didn't invent the motif of woman having sex with octopus. It's found in netsuke of the 17th century, and its inventor is unknown.

Art historians are still asking that question. There's no mystery about the creator of Cooper's print: It's Katsushika Hokusai, otherwise known for The Great Wave. The octopus print, from 1814, is usually known in the English-speaking world as The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife. But Hokusai didn't invent the motif of woman having sex with octopus. It's found in netsuke of the 17th century, and its inventor is unknown.  LACMA has a rare pre-Hokusai woodcut of the theme from c. 1773-4, a gift of the late Max Palevsky. Abalone Fishergirl with an Octopus by Katsukawa Shusho, above, is more understated than Hokusai's orgy. There's no indication that the woman wants the mollusc's attentions. It's simply a monster-menaced damsel. Hokusai's version is not only more "sensual" (as Cooper describes it) but more feminist (as no one on Mad Men would think to describe it). The woman is enjoying herself more than the octopuses are. Perhaps the message is, tentacles are better than men.

LACMA has a rare pre-Hokusai woodcut of the theme from c. 1773-4, a gift of the late Max Palevsky. Abalone Fishergirl with an Octopus by Katsukawa Shusho, above, is more understated than Hokusai's orgy. There's no indication that the woman wants the mollusc's attentions. It's simply a monster-menaced damsel. Hokusai's version is not only more "sensual" (as Cooper describes it) but more feminist (as no one on Mad Men would think to describe it). The woman is enjoying herself more than the octopuses are. Perhaps the message is, tentacles are better than men.The Bushnell netsuke collection has several related pocket sculptures, all probably post-dating the Hokusai print. A Diving Girl and Octopus, attributed to the Kikugawa family, mid 19th-century, is notable for the post-coital face on the octopus.

To many Westerners, any representation of a woman coupling with an octopus will be pornographic. The title of the James Bond flick, Octopussy, barely made it past censors, and the 1990 film Henry and June incurred the first-ever NC-17 rating because it showed the female lead looking at a postcard of the Hokusai print.

To many Westerners, any representation of a woman coupling with an octopus will be pornographic. The title of the James Bond flick, Octopussy, barely made it past censors, and the 1990 film Henry and June incurred the first-ever NC-17 rating because it showed the female lead looking at a postcard of the Hokusai print.  Not unlike the world of Mad Men, modern Japanese culture blends the button-down salaryman with the libidinous rake. As a pop-culture trope, sex with octopus has probably never been more prevalent than it is in today's Japan. There it mostly falls under the rubric of hentai, the naughty brand of anime. The Western art world knows hentai largely via Takashi Murakami and works such as Miss Ko2 and My Lonesome Cowboy (the pictured sculpture, featured in MOCA's "© Murakami", made $15.2 million in a 2008 Sotheby's auction). Murakami's sculptures are no more louche than the popular hentai imagery in comics, videos, video games, and websites. As to the recent history of so-called tentacle rape imagery, it's hard to top the matter-of-fact tone of this paragraph from the Wikipedia article, "Hentai."

Not unlike the world of Mad Men, modern Japanese culture blends the button-down salaryman with the libidinous rake. As a pop-culture trope, sex with octopus has probably never been more prevalent than it is in today's Japan. There it mostly falls under the rubric of hentai, the naughty brand of anime. The Western art world knows hentai largely via Takashi Murakami and works such as Miss Ko2 and My Lonesome Cowboy (the pictured sculpture, featured in MOCA's "© Murakami", made $15.2 million in a 2008 Sotheby's auction). Murakami's sculptures are no more louche than the popular hentai imagery in comics, videos, video games, and websites. As to the recent history of so-called tentacle rape imagery, it's hard to top the matter-of-fact tone of this paragraph from the Wikipedia article, "Hentai.""The Urotsukidoji anime series was created by Toshio Maeda in 1986 and released in America in 1992 by Anime 18. It is most famous for being the first in the tentacle rape genre, though only one scene in the first OVA actually contains any tentacle rape. Tentacle rape was not present in the Urotsukidoji manga, but was featured in a series that he would publish years later called Demon Beast Invasion. Demon Beast Invasion created what might be called the modern paradigm of tentacle porn, in which the elements of sexual assault are emphasized. Maeda explained that he invented the practice to get around strict Japanese censorship regulations, which prohibit the depiction of the penis but apparently do not prohibit showing sexual penetration by a tentacle or similar (often robotic) appendage. Maeda went on to create La Blue Girl, which departs somewhat from its predecessors by lightening the atmosphere with humor, lightly parodying the tentacle rape genre."

In American literature, tentacles have often been a metaphor for the capitalist system. That was the conceit of Frank Norris' The Octopus (1901), a muck-raking tale inspired by the darker side of museum-builder Henry Huntington's Southern Pacific railroad. Over a century later, Rolling Stone characterized Goldman Sachs as a "giant vampire squid." On Mad Men, Bert Cooper says the Hokusai reminds him of the advertising business. We're apparently intended to see it as an emblem of the seductions of our polymorphous consumer economy. Will satisfying the consumer's lust ever make her happy?

Comments

I can't help but hope that this art-knowledgeable show will give us more mid-century feasts for the eye.

Perhaps if the Campbell Soup account comes along with Don Draper et al, we'll see a 1962 Warhol Soup Can on Bert's wall next?

on a totally unrelated note, i'm a little bummed to see no reference to Pulpo Paul in this post. But seeing as you managed to get Sterling Cooper and tentacle rape into one incredible write-up, I will forgive...

anyway, loved the post.