"Becoming America" at the Huntington

The Huntington has opened its new Jonathan and Karin Fielding Wing, a 8600-sq. ft., Frederick Fisher-designed addition to the Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art. The Scott now has 26,000 sq. ft. of exhibition space for American art, matching San Francisco’s de Young Museum (25,000 sq. ft.) LACMA’s American display is only about 9500 sq. ft. Of course, it’s the art that matters, and no other West Coast institution approaches the de Young’s comprehensive collection. But the Huntington’s American display is charting an interesting new direction with “Becoming America: Highlights from the Jonathan and Karin Fielding Collection.” The Fieldings, the wing’s lead donors, collect American folk art, something hardly represented in L.A. museums. “Becoming America” has 200 works, representing everything from quilts to Shaker boxes to scrimshaw. Many of the objects are flat-out spectacular. (At top, the installation’s cover man/mascot, A. Ellis’ 1831 portrait of New Hampshire schoolteacher Albert G. Gilman.)

“Wing” isn’t quite the word. Most of the new space fills in a gap between Paul Gray’s original 1984 Scott Gallery and Fisher’s 2005 addition, the Lois and Robert F. Erburu Gallery. The entrance is a glass house in an American landscape, echoing those of Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson. Fisher cites the influence of Denmark’s Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. The room is both lobby and exhibition space, showing stoneware jugs and a wall of functional American metalwork. It’s a West Coast answer to Albert Barnes’ kooky walls of metalwork.

Fredrik Nilsen’s press photos show the glass box at its best, but window shades were pulled down on opening weekend, diminishing the indoor-outdoor effect.

This glass-walled room has a sightline, through four new galleries, to Fisher’s glass loggia on the other side of the building, showing modern bronze sculptures and views of the San Gabriel Mountains. In all, there are eight new interior galleries. None have skylights in order to accommodate light-sensitive works. One room shows 18th-century furniture and paintings from the recently bequeathed collection of Thomas Oxford and Victor Gail.

“Becoming America” draws on small-town New England, about 1690 through the Civil War. It embraces practical objects never intended as art, plus portraits by self-taught American painters who often had to go on the road to make a living. In the 20th century, this art was celebrated as “modern” before the fact, and it still has that appeal today.

You can think of “Becoming America” as a show of readymades. My favorite “sculpture” is a Ratchet Lighting Device, c. 1720. It’s Giacometti, it’s African, it’s a guillotine… though it seems to have had another practical function. Runner up is a Niddy-noddy (c. 1800), just because I like the name.

A room of chairs upends the usual regimented displays. It’s like all the Founding Fathers and Mothers had a wild party, and everything’s a mess.

Two rooms focus on painting, and they include many of the most prized vernacular artists, such as portraitists Ammi Philips and Sheldon Peck (three paintings each) and marine painters James Bard and Thomas Chambers.

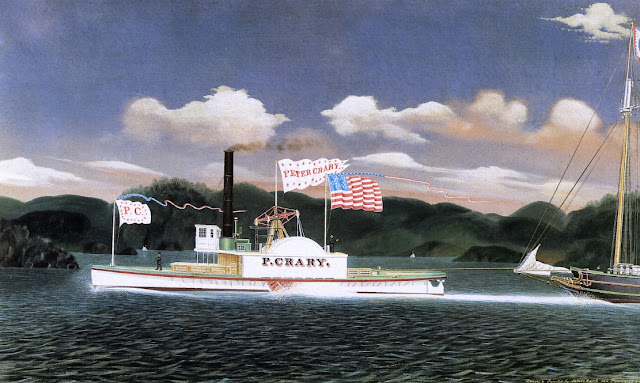

James Bard (1815-1897) demonstrates how the folk aesthetic lingered long past photography and the establishment of an urban art market. Bard was a railroad mechanic who painted ships as a sideline. He died dirt-poor, like many of the artists here, was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in Brooklyn.

Bard’s painting of the steamboat Peter Crary is one of two known. Steamboats were cutting-edge technology. Only the Fielding version shows it tugging an obsolescent(?) sail boat. It’s a steampunk progress of empire.

A. Ellis, author of the eccentric portrait at top of post, is even more of a mystery than Bard. No one knows what the “A.” stood for or what gender it indicated. There are about 15 known A. Ellis paintings, two at upstate New York’s Fenimore Art Museum. In a YouTube video, Jonathan Fielding likens the Gilman portrait to Modigliani. The nose, angled a good 60 degrees from a perpendicular to the facial plane, is more Picasso. The too-close eyes in a too-big head is South Park. It is certainly the cartoony element that grabs the viewer. Albert G. Gilman reads as a caricature, voicing the anxieties that Yankee taciturnity leaves unsaid.

The Fielding collection includes more conventional levels of polish. Sheldon Peck’s A Young Man with a Red Curtain was discovered under a framed print on a 1997 episode of Antiques Roadshow. The widow-peaked gent is more dashing, but perhaps less memorable, than Ellis’ schoolteacher.

Folk art isn’t just white folk. A Still Life with a Basket of Fruit, Flowers and Cornucopia (1860) is attributed to Joseph Proctor, an African-American who lived on New York’s Lower East Side—remote from the art world of the time. Proctor’s Still Life is a pyrotechnic celebration against the darkest of shadows, painted on the eve of Civil War.

Samuel Miller’s Portrait of Cynthia Mary Osborn (c. 1843) is another standout. Cynthia died at age 8, in 1842. Her portrait was posthumous. The child is shown next to a looming red gate, roughly what we’d call the “Pearly Gates.”

The Burning of the Old South Church in Bath, Maine, c. 1854, is post-Turner and pre-Ruscha. Attributed to John Hilling, it records an incident of anti-Catholic immigrant violence. It’s a powerful counterpoint to the idyllic tone struck in most early American painting. The artist did a “before” and “after” pair, the former showing the church as it appeared before the arson. Check out the time on the clock tower: Disaster can strike at any minute.

Fires were incredibly destructive in early America because they had to be put out by buckets, with volunteers drawing water from the nearest well. One pair of fire buckets in “Becoming America” seem too elegant to use. They’re painted leather, c. 1839, with the insignia of the Mechanic Fire Society of Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

The Autry Museum, which also opened new exhibition space this month, is bringing Native Americans into American art history. “Being America” foregrounds the Northeastern nations of the Iroquois, Ojibwe, and Mohegan. Many took up the craft of applying faux finishes to wood. Originally intended to duplicate the grain of expensive imported woods, this type of decoration took on a life of its own. Anonymous was a woman, and “fancy” was often an Indian.

A room of fancy-aesthetic furniture and boxes include an exuberant grain-painted “Matteson” blanket chest of early 1820s Vermont. Some smaller boxes are displayed in a Judd-like set of shelves. This room cleverly offers a glimpse into an Erburu Wing room of 1960s and 70s minimalism.

The new wing makes it easier to cross between galleries devoted to early and modern America. Newly on view at the Scott are loans of modern art, including a 1892 Elihu Vedder bronze fireback, The Sun God; a Fauve-inspired painting, The Soil (1927) by Society of Six founder Selden Connor Gile; and a major Agnes Pelton, Passionflower. The latter, from an unidentified private collection, is part of a stunning line-up of three flower paintings by women modernists. The other two are Henrietta Shore’s Clivia and Helen Lundeberg’s Irises, both recent acquisitions. Of the three, the Pelton is the most aggressively modern, yet also the one that channels the decorative strangeness of American folk art.

|

| Johnathan and Karen Fielding Wing. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen |

“Wing” isn’t quite the word. Most of the new space fills in a gap between Paul Gray’s original 1984 Scott Gallery and Fisher’s 2005 addition, the Lois and Robert F. Erburu Gallery. The entrance is a glass house in an American landscape, echoing those of Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson. Fisher cites the influence of Denmark’s Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. The room is both lobby and exhibition space, showing stoneware jugs and a wall of functional American metalwork. It’s a West Coast answer to Albert Barnes’ kooky walls of metalwork.

|

| Entrance to Fielding Wing. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen |

This glass-walled room has a sightline, through four new galleries, to Fisher’s glass loggia on the other side of the building, showing modern bronze sculptures and views of the San Gabriel Mountains. In all, there are eight new interior galleries. None have skylights in order to accommodate light-sensitive works. One room shows 18th-century furniture and paintings from the recently bequeathed collection of Thomas Oxford and Victor Gail.

“Becoming America” draws on small-town New England, about 1690 through the Civil War. It embraces practical objects never intended as art, plus portraits by self-taught American painters who often had to go on the road to make a living. In the 20th century, this art was celebrated as “modern” before the fact, and it still has that appeal today.

You can think of “Becoming America” as a show of readymades. My favorite “sculpture” is a Ratchet Lighting Device, c. 1720. It’s Giacometti, it’s African, it’s a guillotine… though it seems to have had another practical function. Runner up is a Niddy-noddy (c. 1800), just because I like the name.

A room of chairs upends the usual regimented displays. It’s like all the Founding Fathers and Mothers had a wild party, and everything’s a mess.

Two rooms focus on painting, and they include many of the most prized vernacular artists, such as portraitists Ammi Philips and Sheldon Peck (three paintings each) and marine painters James Bard and Thomas Chambers.

James Bard (1815-1897) demonstrates how the folk aesthetic lingered long past photography and the establishment of an urban art market. Bard was a railroad mechanic who painted ships as a sideline. He died dirt-poor, like many of the artists here, was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in Brooklyn.

Bard’s painting of the steamboat Peter Crary is one of two known. Steamboats were cutting-edge technology. Only the Fielding version shows it tugging an obsolescent(?) sail boat. It’s a steampunk progress of empire.

A. Ellis, author of the eccentric portrait at top of post, is even more of a mystery than Bard. No one knows what the “A.” stood for or what gender it indicated. There are about 15 known A. Ellis paintings, two at upstate New York’s Fenimore Art Museum. In a YouTube video, Jonathan Fielding likens the Gilman portrait to Modigliani. The nose, angled a good 60 degrees from a perpendicular to the facial plane, is more Picasso. The too-close eyes in a too-big head is South Park. It is certainly the cartoony element that grabs the viewer. Albert G. Gilman reads as a caricature, voicing the anxieties that Yankee taciturnity leaves unsaid.

The Fielding collection includes more conventional levels of polish. Sheldon Peck’s A Young Man with a Red Curtain was discovered under a framed print on a 1997 episode of Antiques Roadshow. The widow-peaked gent is more dashing, but perhaps less memorable, than Ellis’ schoolteacher.

Folk art isn’t just white folk. A Still Life with a Basket of Fruit, Flowers and Cornucopia (1860) is attributed to Joseph Proctor, an African-American who lived on New York’s Lower East Side—remote from the art world of the time. Proctor’s Still Life is a pyrotechnic celebration against the darkest of shadows, painted on the eve of Civil War.

Samuel Miller’s Portrait of Cynthia Mary Osborn (c. 1843) is another standout. Cynthia died at age 8, in 1842. Her portrait was posthumous. The child is shown next to a looming red gate, roughly what we’d call the “Pearly Gates.”

The Burning of the Old South Church in Bath, Maine, c. 1854, is post-Turner and pre-Ruscha. Attributed to John Hilling, it records an incident of anti-Catholic immigrant violence. It’s a powerful counterpoint to the idyllic tone struck in most early American painting. The artist did a “before” and “after” pair, the former showing the church as it appeared before the arson. Check out the time on the clock tower: Disaster can strike at any minute.

Fires were incredibly destructive in early America because they had to be put out by buckets, with volunteers drawing water from the nearest well. One pair of fire buckets in “Becoming America” seem too elegant to use. They’re painted leather, c. 1839, with the insignia of the Mechanic Fire Society of Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

The Autry Museum, which also opened new exhibition space this month, is bringing Native Americans into American art history. “Being America” foregrounds the Northeastern nations of the Iroquois, Ojibwe, and Mohegan. Many took up the craft of applying faux finishes to wood. Originally intended to duplicate the grain of expensive imported woods, this type of decoration took on a life of its own. Anonymous was a woman, and “fancy” was often an Indian.

A room of fancy-aesthetic furniture and boxes include an exuberant grain-painted “Matteson” blanket chest of early 1820s Vermont. Some smaller boxes are displayed in a Judd-like set of shelves. This room cleverly offers a glimpse into an Erburu Wing room of 1960s and 70s minimalism.

|

| Photo: Fredrik Nilsen |

Comments