California's First Great Woman Artist

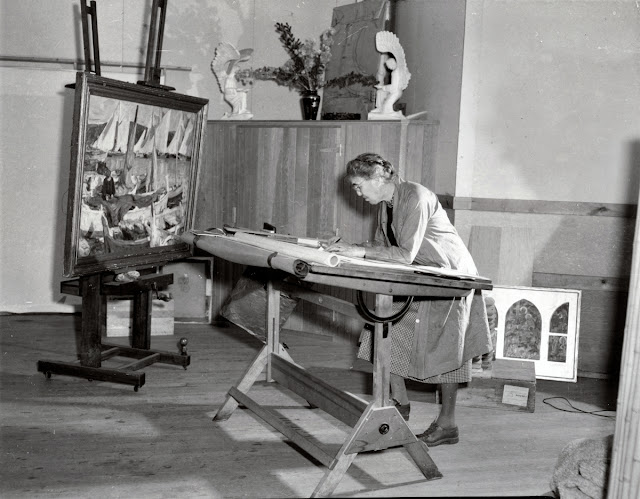

"Why have there been no great women artists?" asked Linda Nochlin in 1971. Her essay invoked Rosa Bonheur, the 19th-century French painter who dressed in male drag to compete in a man's man's man's art world. Bonheur has a 20th-century counterpart in E. Charlton Fortune, subject of a retrospective that has just opened at the Pasadena Museum of California Art. (Shown, Fortune's 1921 Edinburgh Castle.)

Born in Marin County in 1885, Fortune found fame as a woman artist who painted like a man, dressed like a man, and was often assumed by critics to be a man. The E. stood for Euphemia.

PMCA's "E. Charlton Fortune: The Colorful Spirit" traces her career, starting with studies in San Francisco and New York (under Arthur Frank Matthews and William Merritt Chase, respectively). Fortune did the Paris bit, soaking up Monet, Cezanne, and Picasso. She sojourned in the art colonies of Woodstock, St. Ives, and Monterey (where she lived from 1927 on). Monterey was also the home of Henrietta Shore, the Canadian-born modernist who is better known today. Almost certainly a lesbian, Fortune was known for her corduroy suits and affection for a pupil, Ethel McAllister.

By about 1920, Fortune's bold brushwork and subtle cubist influences had elevated her to an advanced circle of American painters. Fortune's most challenging works are often small oil sketches signed to indicate they're finished. Below is Scavengers, St. Ives, 1922. The modern British seacoast is Bodega Bay. The birds are pecking out Monet's eye—but what an eye!

The Depression that ruined many an American fortune ruined Fortune's. Her broad-brush empiricism was thereafter considered dated, lacking the social relevance of the American Scene. She turned to religious painting for churches. In this too she was successful, but the church paintings undercut what remained of her avant-garde reputation. Fortune got a medal from the Pope in 1955 and died forgotten in Carmel, in 1969.

Born in Marin County in 1885, Fortune found fame as a woman artist who painted like a man, dressed like a man, and was often assumed by critics to be a man. The E. stood for Euphemia.

PMCA's "E. Charlton Fortune: The Colorful Spirit" traces her career, starting with studies in San Francisco and New York (under Arthur Frank Matthews and William Merritt Chase, respectively). Fortune did the Paris bit, soaking up Monet, Cezanne, and Picasso. She sojourned in the art colonies of Woodstock, St. Ives, and Monterey (where she lived from 1927 on). Monterey was also the home of Henrietta Shore, the Canadian-born modernist who is better known today. Almost certainly a lesbian, Fortune was known for her corduroy suits and affection for a pupil, Ethel McAllister.

By about 1920, Fortune's bold brushwork and subtle cubist influences had elevated her to an advanced circle of American painters. Fortune's most challenging works are often small oil sketches signed to indicate they're finished. Below is Scavengers, St. Ives, 1922. The modern British seacoast is Bodega Bay. The birds are pecking out Monet's eye—but what an eye!

The Depression that ruined many an American fortune ruined Fortune's. Her broad-brush empiricism was thereafter considered dated, lacking the social relevance of the American Scene. She turned to religious painting for churches. In this too she was successful, but the church paintings undercut what remained of her avant-garde reputation. Fortune got a medal from the Pope in 1955 and died forgotten in Carmel, in 1969.

Comments