All the Watteaus in Los Angeles

Los Angeles had Warhols before it had Watteaus. But now L.A. museums probably have six Watteau paintings, more than New York and San Francisco (three each) or DC and Chicago (two). L.A.'s half-dozen, out of the hundred-some Watteau paintings known to survive, are parceled between five museums. That's testament to the enduring relevance of Watteau and to the enduring egotism of L.A. collectors.

The first Watteau to enter a local institution was The Country Dance (c. 1711) at the Huntington. Not part of Henry and Arabella's collection, it was acquired in 1978 through the Adele S. Browning bequest. The Browning collection had been promised to LACMA, unpromised for obscure reasons, and regifted to the Huntington.

Watteau conceived The Country Dance as a rectangular painting on panel. It is so recorded in a print. By 1789, and over Watteau's dead body, it was cut down to a circle enclosing the dancers. At some latter point Watteau's rondel was set into a rectangular panel and the landscape extended. The replacement background follows the print but isn't, of course, by Watteau's hand.

The Norton Simon Museum's painting has a similar problem. It's 100 percent Watteau and over 50 percent missing. The Getty owns a related drawing that may indicate the artist's original conception. It shows a servant about to administer an enema with an outsized syringe. Enemas were fashionable 18th-century cures and a pretext for leering innuendo. Watteau requested that his more scandalous works be destroyed upon his death.

Despite its fragmentary state Reclining Nude has impressed worthies ranging from Sister Wendy to Christopher Knight. Scholar Donald Posner wrote that "the picture's handing and description of forms are typical of Watteau at his best, and in this work they are more readily appreciated than in many better-known but less well preserved paintings by the artist."

Armand Hammer gave his Westwood museum a murky mess, Festivities in Honor of Pan. It is believed to be an early work (1703-1708) forecasting the subject matter of Watteau's maturity. White-clad Pierrot plays a flageolet for fellow comedians and bare-breasted nymphs. The composition is recorded in an engraving (reversed) by Michel Aubert that is much more legible than the painting now is.

Hammer's New York gallery unloaded Festivities on Morrie Moss, a collector who became an Occidental Petroleum board member. Moss later tried to resell it through the Hammer Gallery, with no success.

Moss and Hammer concocted a Max Bialystock scheme to donate the unsellable painting to a museum for a tax deduction worthy of the great Watteau. The Memphis Brooks Museum of Art agreed to accept the painting as a gift. The catch was that the IRS might not accept the dicey attribution. Memphis Brooks curator Douglas K. S. Hyland sought expert opinion, getting a half-enthusiastic thumb's up from the Louvre's Pierre Rosenberg. Hammer then decided the painting wasn't so bad after all. He bought Festivities from Moss for his personal collection, cutting Memphis Brooks out of the deal. That was the collection Hammer promised to LACMA, before he cut LACMA out of the deal.

Despite the skullduggery the Hammer Watteau is almost never on view in the museum he founded. Though it's not among the lesser (and some major) paintings UCLA returned to the Hammer Foundation in 2007, it's not in good enough condition to merit continuous display.

To recap: LACMA was promised, then stiffed of, two Watteaus. In 1999 the Ahmanson Foundation bought LACMA a quintessential Watteau, better than either of the paintings that had been promised. The title of LACMA's Perfect Accord (1719) must be ironic. The elder flutist and the beautiful young woman holding the music invoke the northern European theme of ill-matched lovers.

The Italian Comedians is large for a Watteau (51 inches high). Scott Schaefer, the Getty curator who championed the purchase, polled ten Watteau experts. Seven said it was least partly by the artist; three denied any participation.

Alan Wintermute, who's writing a Watteau catalogue raisonné, connects the Getty painting to the quite different Italian Comedians at the (U.S.) National Gallery. The Washington Italian Comedians is documented in a early print and is generally accepted as genuine. But the NG painting seems somewhat off too, so much that some scholars have wondered whether it's a early copy of a lost original.

The Washington painting (or a hypothetical original?) was owned by Dr. Richard Mead of London. It's believed that Watteau visited Mead for treatment of tuberculosis, and that the Getty painting was also created in England. The brash paint handling of the costumes of Brighella in DC and LA are similar, departing from the more delicate brushwork of typical Watteaus.

One theory is that Watteau, exposed to a different visual culture in England, modified his style. That might explain why connoisseurs have felt the Getty and National Gallery paintings were suspiciously different. It is hard to imagine that an unknown yet accomplished English follower produced two "Italian Comedians" and that both of Watteau's originals have gone missing.

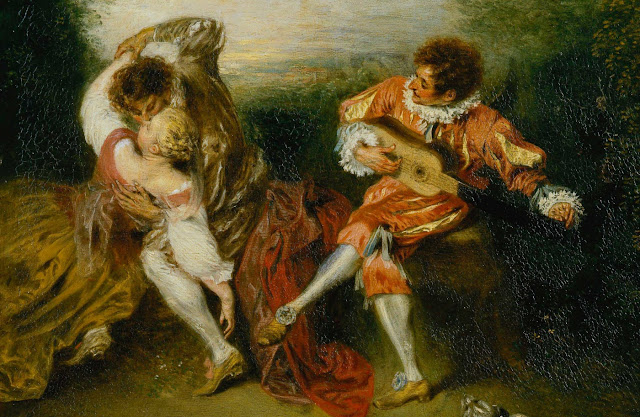

The couple's public display of affection is observed by a guitar-strumming third wheel. The slashed outfit of the musician (probably a Mezzetin) channels van Dyck; the kissing couple and curious dog are adapted from two Rubens paintings. But neither Rubens nor van Dyck would have created a painting without a clear narrative. Nor would a baroque artist likely have conceived the photographic cropping of the swooning woman. Watteau used a compositional cut-up technique, montaging figures from his drawings onto panels.

The Getty Surprise and LACMA Perfect Accord were once in the collection of Nicolas Hénin, consigliere to Louis XV. Hénin hung the two paintings together. After his death they were separated, and both were lost until recently. That they have been reunited in Los Angeles is a fairly amazing coincidence.

The lot note for Christie's 2008 auction of La Surprise reported that when the paintings were briefly reunited at LACMA "they made slightly awkward companions." The LACMA figures are closer to the picture plane. The landscapes don't quite match. So maybe it's okay they're not sharing the same museum wall. The Getty has hung The Surprise in a South Pavilion room with the Italian Comedians, near paintings on l'amour by de Troy, Lancret, Fragonard, and Greuze.

In January 2018 The Surprise will go on view in an installation of European drawings acquired from the same seller, U.K. collector Luca Padulli.

Comments